A thick cloud of dust rose as a string of horse-drawn cannons thundered across the Pennsylvania countryside on July 2, 1863. Though the afternoon was blazingly hot, there wasn’t a minute to lose. The Battle of Gettysburg was in its second day. The fighting was savage and there was no way of knowing which side would prevail. Only one thing was certain: Everyone from the lowest private to the top generals recognized this was a pivotal moment in American history.

Because this battle held the very real possibility of determining not only the war’s outcome but the country’s destiny as well.

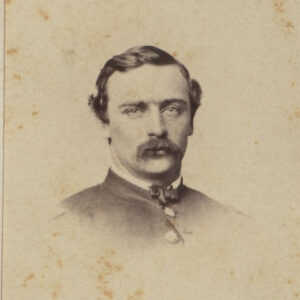

With the stakes incalculably high and the fog of war swirling all around, Lt. Gulian Weir dashed up to the Union commander in that sector and asked for his orders. Maj. Gen. William Scott Hancock, “Hancock the Superb” he was called, directed the six cannons of Battery C, 5th U.S. Artillery straight to the front line.

It was an unenviable assignment. The 27 year-old-Weir immediately rolled his guns into position—just as the Confederates launched a massive attack. His little battery fired furiously into the oncoming Southerners; the gunners were shooting so fast, they quickly went through their entire supply of ammunition. And still, the enemy kept coming.

Weir’s horse was shot out from under him. Rising from the ground, he was hit by a spent rifle ball and left momentarily dazed and confused. The scene was total chaos.

The young lieutenant finally had no choice but to instruct his cannoneers to attach their guns to their horses and run to the rear. But it was too late. The infantry that should have supported them had been pushed back, and with Southern troops coming at them from multiple directions, only three of Weir’s cannons escaped. The other three fell into the enemy’s hands as the horses were shot dead. (Those three field pieces were later retaken in a Federal countercharge.)

It was the best poor Weir could do in a terrible situation. Probably no other artillery commander, Union or Confederate, could have done better. He served honorably for the rest of the war, rising to become captain of Battery L. It was a record most soldiers would have claimed with pride.

But Weir couldn’t. Because Hancock harshly criticized Weir for losing those three cannons in his official report on the battle. Once it was made public, the whispers began. Weir was a coward; Weir had fled in the face of the enemy; Weir wasn’t man enough to meet the challenge.

Saying those words cut like a knife doesn’t do their injury justice. A West Point educated son of a military officer, Weir prided himself in being a professional soldier. The accusation that he had abandoned his guns at a crucial moment in the heat of battle wounded him to his very soul.

Weir remained in the Army after the war and did what many young veterans also did: he married and started a family. But he was still haunted by what had happened on that hot July afternoon.

He eventually wrote to Hancock—several times, in fact—apologizing for intruding on his former commander’s time and then almost begging him for some type of statement modifying his report or forgiving him. No reply from Hancock (who was the Democrat’s presidential nominee in 1880), is known to exist.

Emotionally spent and spiritually exhausted, Weir visited the Gettysburg battlefield in 1885, desperately seeking some way to make peace with his past. He didn’t find it.

Then came another July day in 1886. Weir was stationed at Fort Hamilton, N.Y. By all accounts, he seemed “bright and cheerful” on Sunday the 18th. After finishing dinner, he quietly retired to his upstairs room in the officers’ quarters, sat down in a chair, aimed a .45 caliber Springfield rifle at his heart, and ended his suffering.

He was 48 and the father of six children. The youngest, his namesake born the same year Weir died, went on to serve as a captain in World War I. Perhaps he was emulating the father he never knew.

Though his end came 23 years after the battle, you could say Gulian Weir was the last casualty of Gettysburg, struck down by a bullet fired not by a foe, but by an unforgiven burden from which he could not break free.