Think quick! You’re a jeweler. You’ve got a gemstone. And an organization is waiting for it some 225 miles away. What do you do?

A merchant once pondered that very question. But it wasn’t just any jeweler shipping any precious stone to any old group. It involved America’s foremost jeweler at the time, the most famous gem in the world, and America’s most celebrated museum.

And how he wound up sending it will amaze you.

To fully appreciate this story, you must first understand the players involved.

Harry Winston was the American Dream come true. Son of struggling Jewish immigrants from Russia, at age 12 something caught his eye in a neighborhood pawnshop. The boy recognized it as a two-carat emerald and plopped down a quarter to pay for it. Two days later he sold it for $800 (nearly $25,000 today).

No surprise then that he had his own jewelry shop at age 24. He made his name in 1926 by buying Arabella Huntington’s fabulous collection of some of the world’s most beautiful jewels. Her husband was a railroad magnate, and she spent a big chunk of his fortune on pretty things that sparkled and glittered.

Harry H. Winston Jewels, Inc. opened in New York in 1932, becoming simply Harry Winston, Inc. in 1936. It remains the gold standard for purveyors of precious stones.

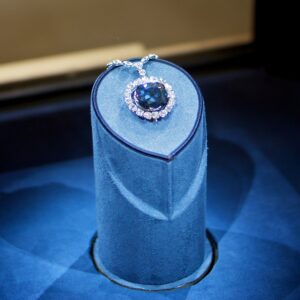

In 1949, Harry cemented his reputation by getting hold of the Big Kahuna, the most legendary jewel of them all: The Hope Diamond.

That 45.52-carat blue stunner had dazzled and delighted folks for four centuries. Unearthed in India in the 1600s, it was cut down from its original mammoth size into the piece we know today and gained a new nickname, the “French Blue.” It also acquired a reputation for bad luck. Really bad luck, in fact. Consider the high body count left in its wake.

An early owner was King Louis 16th of France who, if you remember your high school history, wound up on a date with Madame Guillotine. A 1911 New York Times article about people who came in contact with it was a rogue’s gallery of murders, suicides, and other less than savory endings.

The Hope banking family owned it for a while, which was how it came to be tagged with the name we know today. Lord Henry Thomas Hope was in debt up to his chin, so in 1902 he sold it to a New York firm for a then-staggering $148,000. That was how it wound up on this side of the Atlantic.

It eventually settled in the hands of preeminent Washington socialite Evelyn Walsh McLean, who let her friends Warren G. and Florence Harding try it on. Harding later unexpectedly died in a San Francisco hotel room in 1923.

The diamond came to be considered cursed. Though research later cast serious doubt about the validity of the many awful endings associated with it, the lurid stories only added to its mystique. Its ill-fated reputation still lingers.

Harry Winston purchased the fabled stone in 1949 (at which time it seems people around it suddenly stopped dropping dead). It’s not known what the purchase price was, but you can bet it didn’t come cheap.

Owning the crown jewel of all jewels was a major feather in Harry’s cap. He proudly toured it around the U.S. for nine years (promoting Harry Winston, Inc. at the same time).

In 1958, Harry did something spectacular. He donated the Hope Diamond to the Smithsonian Institution, which was only too delighted to add it to its magnificent collection.

Which brings us back to the question posed at the beginning. How do you move such a precious item from New York to Washington?

You mail it, of course.

No, really. It happened.

On Nov. 8, 1958, the most famous jewel in the world was put into a typical manila mailing envelope. To it was affixed labels showing a total of $145.29 for registered first-class delivery to D.C. Interestingly, only $2.44 was for the actual postage; the rest covered insurance for $1 million (more than $10.2 million today, a mere fraction of its worth).

Why go postal? At the time, the post office was considered the safest source for delivering valuables. And there was an added benefit. Tampering with the mail is a federal offense, meaning had it been stolen en route the FBI would have been tasked with finding it. No private security firm could match J. Edgar Hoover’s G-men.

The Hope Diamond arrived safely and went on display, where it still delights thousands of Smithsonian visitors yearly. Presumably without bringing bad luck home with them, too.