That corny country TV variety show “Hee-Haw” had a gag called, “Gloom, Despair, and Agony on Me.” Hillbilly sad sacks laid around a cabin porch and wailed in woebegone misery, “If it weren’t for bad luck I’d have no luck at all.”

That was a comedy sketch. But the man we’re about to meet could have sung those words and meant them. Because if anybody was ever born under an unlucky star, it was Ambrose Everett Burnside.

It’s not that Burnside was a bad guy. Far from it. But he couldn’t have caught a lucky break had he paid for it.

Born in Indiana in 1824, he grew up in Rhode Island. He later graduated from West Point. So far, so good. Then things went rapidly downhill.

Burnside joined the army in time for the Mexican War. Heading for the action south of the border he was cleaned out by riverboat gamblers. Arriving after the fighting was over, he was stuck pulling guard duty in Mexico City.

Switching to the cavalry, he spent the next few years chasing natives around the Southwest and was rewarded with an arrow shot into his neck for his efforts.

In 1853, he went home, met a nice woman, and proposed. During the wedding ceremony, when the minister asked the traditional question, she answered, “No,” leaving him standing at the altar.

Burnside then tried his hand at inventing, designing a modern repeating rifle. He founded the Burnside Arms Company to produce and sell the gun…whereupon his usual pattern of failure returned. Good as it was, the carbine was just too expensive for the cash-strapped U.S. government of the late 1850s. Burnside ran for Congress, and of course, lost. Then his gun factory burned down, and with it went all his money. To pay off his creditors, he sold the patents to his firearms–right as the Civil War was about to erupt. Washington bought thousands of the guns, the guy who bought the patents made millions, and Burnside was left holding the bag.

The War Between the States was the next stop on Burnside’s path of failure, and where he really did it up big. He joined the Union army and quickly rose to major general

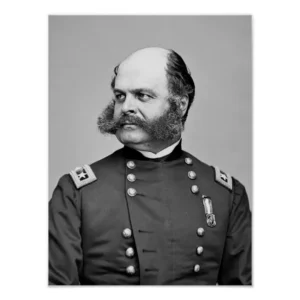

Here’s the thing about Ambrose Burnside: He naturally, and without effort, presented the aura of a guy who had it all together. When people met him, they thought, “Wow!” It’s not that he tried to deceive anybody; quiet, decent, and gentle, he nonetheless gave off a confident vibe that left people in awe. But an officer who served under him said, “You had to be around him for a while to realize he just wasn’t that smart.”

He proved that with the blood of his soldiers in September 1862 at Antietam, when he ordered repeated attacks across a stone structure now called Burnside’s Bridge. Some 450 Georgians on the opposite hilltop held off 14,000 Union troops for hours during charge after charge, killing many of them. A scout later discovered the Yankees could easily wade the creek downstream, avoiding the Rebel stronghold.

Just weeks after that disaster, President Abraham Lincoln appointed Burnside commander of the Army of the Potomac. Historian Bruce Catton wrote, “It was to Burnside’s eternal credit that he told Lincoln he wasn’t up to the job, and to Lincoln’s eternal discredit that he didn’t listen.”

Burnside hurled the entire Union army uphill at entrenched Confederates waiting for it at Fredericksburg, Virginia. The result: 12,653 men were mowed down.

He was then bounced from one second-tier command to another for the remainder of the war. The general was in Washington when Lee surrendered and decided to celebrate the war’s end by seeing a play. You guessed it: He was sitting directly below Lincoln’s box in Ford’s Theatre when John Wilkes Booth crept inside it. In fact, the president was looking down at the time, and Burnside was among the last faces Lincoln ever saw.

Surprisingly after his unbroken string of failure, Burnside returned to Rhode Island with his popularity intact. He was elected governor, helped found the National Rifle Association, and capped it off by winning election to the U.S. Senate. He died of a heart attack in 1881 at age 57.

Burnside was unlucky one last time. Famous for the distinctive whiskers worn on his cheeks, people called the style “burnsides.” But he was denied his claim to fame. Somehow, the name was inverted: You and I know them as “sideburns.”

“If it weren’t for bad luck, I’d have no luck at all.” In Ambrose Burnside’s case, truer words were never sung.