So, you want to spend this Memorial Day in the town where the holiday began. Take your pick. After all, you have 25 communities to choose from.

Experts will tell you wading into identifying the town where Memorial Day started is a risky business. Call it the third rail of American history; touching it can give researchers a serious jolt.

Let’s start with what we know for sure. Back in 1868, Gen. John “Black Jack” Logan was commander in chief of the Grand Army of the Republic. It was an organization of Union Civil War veterans, much like today’s American Legion and Veterans of Foreign Wars. He urged that May 30 be observed as Decoration Day, a time to place flowers on the graves of Northern war dead. It’s believed the 30th was selected because flowers would be blooming all around the country by then.

A large ceremony was held that first Decoration Day at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia, where future President James Garfield spoke for an hour and a half. Ulysses S. Grant, who would become president himself 10 months later, and much of the Union Army’s big brass were also on hand. It was the first of Arlington’s annual May observances honoring the fallen, a tradition that carries on to this day.

But when you go back beyond 1868 things get very murky, very fast. Claims of which community commenced the custom are frequent and intense.

There’s Columbus, Miss., where on April 25, 1866, ladies laid flowers on the graves of Confederate soldiers killed in the nearby bloody Battle of Shiloh. Farther east, Columbus and Macon, Ga., each say it got the ball rolling with observances there. A cemetery in Carbondale, Ill., Logan’s wartime home, contains a stone proclaiming the first Memorial Day observance was held there on April 29, 1866. Charleston, S.C., Richmond, Va., Boalsburg, Pa., and many other localities all boast the honor as theirs.

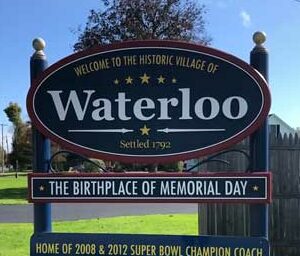

In 1966, Congress waded into the dispute by declaring Waterloo, N.Y., to be the holiday’s official birthplace. Why Waterloo? It seems a special day of observance was held there on May 6, 1866. Stores were closed, flags were flown at half-staff, and, of course, graves were decorated with flowers. That, Waterloo’s supporters argue, shows it was an organized townwide event. Incidents in other places, they say, were just ad hoc groups of women taking flowers to the local cemetery. Waterloo’s observance had all the hallmarks of a true holiday and Congress eventually agreed.

But that didn’t stop the bickering.

In the 56 years since the official designation was bestowed, adherents of other towns’ claim to the title keep arguing for a transfer. They’ll likely still be arguing about it 56 years from now, too. There’s even a separate debate over which town hosts the nation’s oldest continuously running Memorial Day parade. Doylestown, Pa., has a parade that has been held since 1868. But the parade in Rochester, Wis., started in 1867.

It’s worth noting that in spring 1917, just as America was entering World War I, the holiday’s focus began shifting from decorating just Civil War graves to honoring everyone who fell in all American wars.

After World War II, the name began changing from the quaint Decoration Day to Memorial Day. In 1968, Congress passed the Uniform Monday Holiday Act, both cementing the new name and moving its observance to the last Monday in May.

One important parting note: At the conclusion of Arlington National Cemetery’s first ceremony in 1868, children from the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Orphans’ Home walked among the rows of tombstones, singing hymns as they strewed flowers on all graves, both Union and Confederate. The very children who had lived through the war and lost their fathers in its carnage paid tribute to their parents’ adversaries.

Given how deeply (and increasingly) divided the country is in 2022, where people are all too eager to tear into anyone they disagree with or destroy anything they don’t like, it would be well to revisit 1868’s example so that once more “a little child shall lead them.”