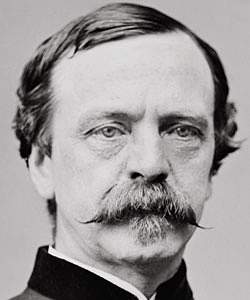

If there is ever a Bad Boy of American History Hall of Fame, Dan Sickles should get his own wing.

He served in Congress; married a woman half his age; murdered her lover and beat the rap with a dubious legal defense; became a Civil War general, losing a leg while nearly losing a big battle; dabbled in diplomacy and fooled around with a queen; filled his pockets with money that wasn’t his; received the Congressional Medal of Honor; and lived to be 94.

Oh, and he did something weird with his lost leg, too.

Daniel Sickles started life working in a New York print shop and studying law. So far, so good.

Then everything went haywire.

At age 33, he married a 15-year-old girl, understandably upsetting both families. Elected to New York’s legislature he was reprimanded for bringing a prostitute into the Senate chamber.

A stint in Congress followed. Sickles quickly made himself notorious there, too.

Discovering his wife was having an affair with Phillip Barton Key, son of Francis Scott Key (of Star-Spangled Banner fame), Sickles spotted Key in Lafayette Park, pulled out a gun, and killed him. Then he calmly confessed to the crime and turned himself in.

The Congressman Killer got the kid-glove treatment. So many senators, congressmen, and society types visited, Sickles was given the jailer’s personal apartment. President James Buchanan sent a handwritten note of encouragement. Sickles even kept the murder weapon!

His legal Dream Team had Mrs. Sickles submit a tear-jerker statement confessing her infidelity. Sickles made sure newspapers ran it. Then his lawyer gambled on a legal technique that had never been tried in the U.S. He argued Sickles was so enraged he was momentarily mad and thus wasn’t responsible for pulling the trigger. It was temporary insanity.

And it worked. Sickles was acquitted. But his popularity vanished because of what he did next.

Sickles forgave his wife.

Americans were outraged! Not because he’d killed a man, not because he literally got away with murder, but because he stayed married to a “fallen woman.” With his approval ratings nosediving, Sickles knew he had to do something fast to restore his image.

The Civil War came to his rescue.

Patriotism, they say, is the last refuge of a scoundrel. Sickles made a big show of marching off to war as colonel of a New York infantry regiment. He pulled strings in Washington and in weeks was a general. By 1863, he commanded an entire corps of the Army of the Potomac.

Fast forward to that July. Ordered to take up a position south of Gettysburg, Sickles had a better idea. Against orders, and without telling anyone, he sent his men several hundred yards forward into a peach orchard, making them vulnerable to attack from multiple sides.

Union commander George Meade ordered all corps commanders to meet at his headquarters. “Where’s Dan Sickles?” he asked when everyone had assembled. An officer pointed to the peach orchard. History failed to record the torrent of obscenity that followed.

The Confederates fell upon Sickles’ men like a thunderstorm. A cannonball slammed into his right leg, mangling it beyond recovery. Sickles was carried off on a stretcher, calmly smoking a cigar while shouting words of encouragement. The leg was amputated hours later. Sent to Washington to recover, he told reporters his version of events, thus making sure Dan Sickles looked good in newspaper accounts. And while Sickles healed, his amputated leg was with him.

It sounds creepy, but there was a reason for keeping the lost limb. The surgeon general had recently asked that “specimens of morbid anatomy…together with projectiles and foreign bodies removed” be forwarded to the new Army Medical Museum in Washington. Studying them produced advancements in medical science.

The general wanted to be helpful, but in true Sickles style, he carried it to an extreme. He had a special wooden coffin made for his bones, accompanied by a card reading, “With the compliments of Major General D.E.S.” For years thereafter, Sickles visited the leg in the museum on the amputation’s anniversary. Strange, even for Victorian times, when strangeness was the rule rather than the exception.

Sickles spent the next 50 years hobbling around on crutches. There was no fallout from disobeying orders at Gettysburg. Sickles’ friends in D.C. made sure of that.

He later served as U.S. ambassador to Spain, where President Ulysses Grant figured Sickles couldn’t get into mischief.

Grant figured wrong.

Even with crutches and one leg, it was widely believed Sickles had an affair with Spain’s Queen Isabella II. In 1871, he married a wealthy and beautiful senorita (his poor, soiled dove of a first wife having died of tuberculosis). Returning home, Sickles was even elected to Congress one final time. Incredibly, the man who had defied his commander’s orders was given the Congressional Medal of Honor at age 75 for his “heroism” at Gettysburg! (Again, it paid to know the right people.)

When his body finally wore out in 1914, tens of thousands of people lined New York’s streets for the funeral procession. He was buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

But Sickles remained Sickles right up to the very end. For many years, he served on a commission that raised money to erect monuments to New York’s Civil War soldiers—until $27,000 (almost $150,000 in today’s money) turned up missing. That was the end of his association with the commission.

All major Union commanders at Gettysburg are represented by statues—except Sickles. Asked about that omission late in life he replied with characteristic bravado, “The entire battlefield is a memorial to Dan Sickles.”

He’s been gone for more than 100 years now, but you can glimpse Sickles’ bones at Washington’s National Museum of Health and Medicine.

Love him or hate him, you’ll have to look hard to find anyone else like him.