History is filled with an amazing panoply of people. There are heroes and villains, saints and scoundrels — not to mention a healthy smattering of kooks, crazies, and crackpots. This is the story of one of them and the product he (indirectly) gave us. During the time you spend reading this, dozens of boxes containing it will be purchased. It will be handed to countless kids as a snack. Maybe a camper or two will even use to make a beloved fireside treat.

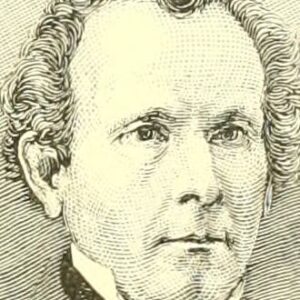

And it’s all thanks to an eccentric named Sylvester Graham. To understand this odd character, you must first understand his odd upbringing. Some men, it could be said, are born kooks. Others have kookery thrust upon them. Graham was the latter.

Born in Connecticut in 1794 as the last of 17 (that’s right—17!) children, his father was 72 and his mother was mentally unstable. The dad died two years later, and little Graham was bounced from one relative to another. One ran a tavern where the boy worked to earn his keep. Seeing drunkenness up close (and likely having to clean up its unpleasant consequences) created a deep hatred of alcohol in him.

A sickly child, his many jobs as a farmhand, cleaner, and incredibly enough schoolteacher left huge gaps in his education. Graham somehow got it in his head that becoming a man of the cloth would cure him of his ailments.

So, he headed off to Amherst Academy in his late 20 to follow in the footsteps of his father and grandfather as a minister. His fellow students laughed at him for his bombastic manner, and he was kicked out of college a year later, triggering a nervous breakdown.

Recovering in Rhode Island, he married the woman who nursed him back to health. He became a sort of freelance Presbyterian preacher. He started working with the Philadelphia Temperance Society in 1830 but left six months later to spread a different kind of message. That’s when things really got interesting.

A cholera epidemic was rampaging across the globe at the time, bringing death and tragedy to the U.S. In that climate, Graham found a ready audience eager to hear his message of better health through clean eating and living. Some of his views were insightful and so far ahead of their time he can arguably be called America’s first Health Guru.

Some of his other ideas, however, were downright absurd.

Alcohol and tobacco were bad in his book. But so was meat and, hard as this is to believe, a common staple. “Thousands in civic life will for years, and perhaps as long as they live, eat the most miserable trash that can be imagined in the form of bread,” Graham wrote.

That’s right. Common bread — as in “give us this day our daily bread” — was the worst dietary bugaboo of them all in Graham’s eyes. He believed consuming it led to other unhealthy habits. He encouraged people to become vegetarians and follow Adam and Eve’s example in the Garden of Eden by eating only plants.

In the place of traditional bread, he pushed a variety made at home by grinding unbleached, unsifted flour taken from wheat berries and making it into a coarse, fibrous plank.

You know it as the “Graham cracker.”

Graham also taught that stress led to health problems, which later research confirmed. But most of his other notions were pure hokum. They included sleeping with an open window, even in winter; sleeping on hard beds; and limiting sex strictly to human procreation. His so-called Graham Diet (which could more accurately be called the Graham Lifestyle) was enthusiastically observed by followers who were called Grahamites.

When the Cholera Epidemic hit New York City in 1832, those who practiced the Graham Diet seemed to avoid the illness. That, coupled with his fiery preaching, put him on the map. Despite a rocky start in life, he had reached the big time.

While Sylvester Graham may have been a crackpot, he wasn’t a conman. He didn’t personally profit from his principles. He sincerely believed they would produce a better quality of life for all who practiced them.

His reputation suffered a severe hit in the closing days of his life. Sick again (this time caused by taking opium enemas), Graham turned to two of the very evils he preached loudest against—alcohol and meat—in a desperate bid to stay alive. They didn’t work. He died at age 57 in his Massachusetts home.

Ironically, he had nothing to do with the product that still bears his name. Commercial bakeries began selling graham crackers around 1900. It wasn’t until 1925 that Honey Maid made them sweeter and turned them into the treat we know today.

And so, Sylvester Graham’s flawed legacy lives on in a corrupted incarnation of his original vision. In a way, it’s a fitting tribute for a man who tried so hard to do good and yet got so much wrong.