Native American women are one of the most victimized demographics in America today. On reservations, rates of violence can be up to 10 times higher than the national average, and murder is the third-leading cause of death for Native American and Native Alaskan women. But the vast majority of Native Americans (some 71 percent) live in urban areas, where local law enforcement should be responsible for investigating any deaths or disappearances. A new report by the Urban Indian Health Institute (UIHI) shows that this is not happening in far too many cases.

The UIHI recently conducted a study of missing and murdered indigenous women across the U.S. They hoped to learn why obtaining data on this violence is so difficult and how law enforcement was responding to the problem.

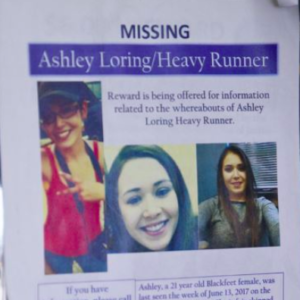

What they found, was a mess. Patchy data and errors in how a victim’s race was recorded meant that many of these women and girls ended up going missing twice–first when they disappear from their communities, and again when their cases fall through the cracks in federal and state databases.

“The lack of good data and the resulting lack of understanding about the violence perpetrated against urban American Indian and Alaska Native women and girls is appalling and adds to the historical and ongoing trauma American Indian and Alaska Native people have experienced for generations,” the report’s authors wrote, laying out a grim picture of how little is known about the widespread problem.

Using Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests, the UIHI requested all case data on missing and murdered Native American women from 1900 to the present from 71 cities across the country with large urban Native American populations. They found 506 records, even as the data range was left broad to try to capture more records. Roughly two thirds of the records recovered are from the last eight years.

These numbers are unusual, since the National Crime Information Center listed 5,712 reported cases of missing or murdered indigenous women in 2017 alone. But the Department of Justice’s missing persons database only included 117 of them. While some of the difference between the two totals is due to the urban/reservation distinction, the size of the discrepancy shows that the current record keeping system is flawed. Exacerbating the problem, the UIHI received no records from some of the law enforcement agencies, and was able to find an additional 153 cases that never appeared in police records at all. These missing persons cases were discovered through searches of news reports, government databases, and social media.

“If this report demonstrates one powerful conclusion, it is that if we rely solely on law enforcement or media for an awareness or understanding of the issue, we will have a deeply inaccurate picture of the realities, minimizing the extent to which our urban American Indian and Alaska Native sisters experience this violence,” the report concludes. “This inaccurate picture limits our ability to address this issue at policy, programing, and advocacy levels.”

The report focuses only on the records, without digging into potential causes for this lack of communication. While the missing women are a serious concern, focusing on the records is a curious starting place. Gaps in databases and records reflect gaps in cooperation between a victim’s family and friends and law enforcement, and between different law enforcement organization.

“I think that this report is really looking at things at the end of the pipeline,” Naomi Schaefer Riley, author of The New Trail of Tears, a book critiquing federal policy towards Native Americans, told InsideSources. She sees the problem of missing records as the last step in a broader step of issues relating to how government handles Indian tribes and reservations.

“They are saying that they are having trouble getting information about these women, that the media is not reporting enough on these. I think that something much earlier is going on.”

Riley believes that confusion about jurisdiction on reservations is a “government failure.” Even in cases where missing women may live off of the reservation, these confusion extends to uncertainty about who should handle the cases and how. It also makes it more difficult for family and friends to offer help.

Last year, Sen. Heidi Heitkamp (D, N.D.) introduced a bill to standardize law enforcement protocols relating to missing and murdered Native Americans. Although the bill attracted sixteen cosponsors, it never made it out of committee.

Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D, Mass.) was an original cosponsorer of the bill and commended the UHI report for confirming the problem of the lack of data.

“This painstakingly-researched report is a much-needed wake-up call to policymakers and officials across the country,” Warren wrote. “The report confirms that the United States faces a crisis when it comes to the issue of missing and murdered indigenous women and girls, and the lack of accurate data and appropriate media coverage has played a crucial role in the epidemic.”

Data may help to find women who have gone missing, or to bring to justice the people who have hurt them. However, the problem is deeper than that.

“This is a difficult conversation for many people, but, statistically speaking, Native women are more likely to be sexually assaulted and more likely to meet violent deaths than women of other races,” Riley said, preventing violence means being able to stop abusers earlier on.

Her solution is not more media attention. Instead, she advises treating it like a crime problem, with better policing, a reform of the court system, and better use of resources. When law enforcement struggles to gather the numbers, even that is difficult.

“American Indians are American citizens and they are due the same legal protections that the rest of us are. We wouldn’t want to live in communities that had this level of lawlessness and violence, and neither should they,” she concluded.