While the rest of the nation struggles to overcome pandemic learning losses and surmount the fractiousness dogging school districts everywhere, one very large school system that services 70,000 students is succeeding despite great tumult.

Although not a perfect analogy with the K-12 system writ large, the success of the network of schools responsible for teaching military-connected children could offer insights into mitigating huge educational disruption.

The Department of Defense Education Activity, or DoDEA, is a federally operated school system that provides pre-kindergarten through grade 12 education for the children of military service members and Department of Defense civilian employees. In 2021, DoDEA operated 160 schools in three regions — U.S. installations in the Americas, Europe and the Pacific.

A government report released recently examined how these children performed through 2019 on the standardized National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) tests compared to other U.S. kids — and it shows that military-connected students in DoDEA schools are excelling.

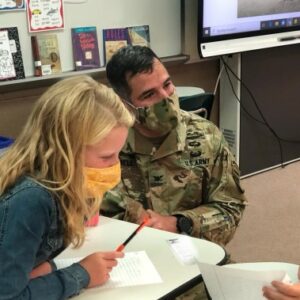

Colonel Jeremy D. Bell, Fort Campbell garrison commander (center), talks with Andre Lucas Elementary School students about their first week of school experiences. Bell joined Christy Huddleston, Department of Defense Education Activity Americas Southeast District superintendent, Aug. 28, as she visited several Fort Campbell schools. U.S. Army Garrison-Fort Campbell and DoDEA partnered throughout the summer to ensure the schools were COVID-19 compliant and safe for the students’ return to the classroom. (Photo Credit: U.S. Army)

It’s an amazing feat, especially given that military-connected children lead highly disrupted lives. They change schools every two to three years with a parent on active duty. And with a parent sometimes deployed doing dangerous work, the children face stress others do not as they manage schoolwork, home responsibilities, and transition in and out of communities.

“Over the past decade, DoDEA students in the fourth and eighth grades have generally received among the highest assessment scores nationwide in mathematics and reading, according to our analysis of NAEP data,” the Government Accountability Office report found.

In the most recent data examined by the GAO for 2019, DoDEA’s average scores for the fourth-grade mathematics and reading assessments were higher than 98 percent and 100 percent of states, respectively. Similarly, DoDEA’s average scores for the eighth-grade mathematics and reading assessments were higher than 94 percent and 100 percent of states, respectively.

The GAO found high levels of achievement when broken down along racial lines and for students with disabilities or students who are English learners.

It wasn’t always this good for military-connected kids. The GAO report notes that in 2011, DoDEA schools were closer to the bottom of the pack, with only 37 percent of states having lower scores on grade four mathematics.

DoDEA director Tom Brady said a turning point came in 2016 when the school system began implementing college- and career-ready standards starting with mathematics. Also, it made a big investment in stepped-up teacher and leader development that has continued over the last nine years.

“Our commitment to student achievement and to teacher training and development all combined for positive development in the classroom,” he said.

Jeffrey Noel, DoDEA’s chief of educational research, added that some of the success can be attributed to an overriding philosophy that guides use of resources. DoDEA schools focus on limiting excessive bureaucracy — a big problem for many school districts — and instead prioritize efforts that can have the most effect on students.

One was a push for in-person instruction. DoDEA schools shifted to remote learning during early 2020 like most other public-school districts. But only months later, by the beginning of the school year in September 2020, DoDEA focused on in-person learning with mitigation measures as many school districts were unable to reopen. By March 2021, 99 percent of DoDEA schools were operating in person and 100 percent by this past fall.

NAEP results are unavailable after 2019, so there is no perfect comparison to past scores and whether they held up in the tumultuous pandemic years. But in the 2020-2021 school year, when many school districts declined to administer tests — or tested only a small portion of students on their traditional annual standardized assessments, DoDEA tested nearly all students. The results indicate that student achievement remained steady and consistent with pre-pandemic levels for most and showed increases in scores for students of color.

Military-connected kids who attend DoDEA schools are not the typical public-school cohort. They have parents with jobs, healthcare, food and housing; their schools are well-funded and don’t have the same federally imposed requirements. They also operate in a unique system of a shared culture and familiarity between students, parents, teachers, school faculty and base leaders.

But they don’t have it easy either.

DoDEA schools are succeeding — and that merits notice. Perhaps their approach for managing students with highly disrupted K-12 careers can provide insights for weathering something as damaging to student learning as a pandemic.