The term “career politician” has become pejorative in American politics.

Even presidential candidates — some with long careers in public service — attempt to claim outsider status, as if experience is a liability. They can hardly be blamed for shunning the label “politician,” but that title used to convey a sense of honor.

What we really need are fewer career politicians and more professional politicians. Not “professional” in the sense of earning a salary, but rather in establishing a set of professional commitments.

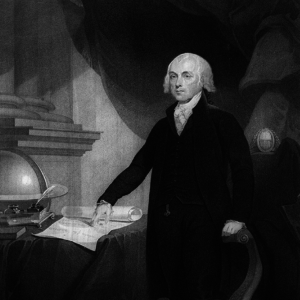

The idea of a “citizen legislator” who takes leave from a day job to spend some time as a public servant is knitted into the fabric of the American experiment. George Washington was eager to return to his farm at Mount Vernon, but he was the exception in the early republic. James Madison, himself a career politician, noted the “grave consequences” of political inexperience, since inexperienced elected officials are more likely to lean on their unelected staff, deepening the divisions between representatives and people.

What would it look like if politicians bought into the duties and expectations that have earned doctors, lawyers and teachers the honorable title of “professional”?

The intellectual component of a profession goes far beyond a doctor’s expertise in anatomy, a lawyer’s knowledge of the art of statutes, or a legislator’s keen sense of crafting the complex text of a bill. Sociologist Everett Hughes noted that professionals are able to blend knowledge from multiple fields to give advice and make decisions at the intersection of multiple disciplines. They push beyond conventional wisdom and emotion. They inquire deeply and struggle to find order and possibility amid confusion and conflict. They creatively engage with challenges in ways that are missing from the ranks of political service.

The professional’s commitment to serve society creates a unique structure of dual loyalties. Lawyers serve their clients’ interests, but they also share evidence with the opposition and prevent witnesses from lying — even if it would help their client — because they have professed loyalty to the system of justice in which they work. Accountants present their clients’ financial information as clearly and beneficially as possible, but they also possess an underlying commitment to preserve the quality of information in the marketplace.

Edmund Burke was highlighting the tenuous but vital nature of this dual loyalty in politics when he said, “Your representative owes you, not his industry only, but his judgment; and he betrays, instead of serving you, if he sacrifices it to your opinion.”

A truly professional politician would be aware of his constituents’ needs and desires, certainly. But he would also feel an obligation to the long-term interests and sustainable prosperity of all governed people. A professional politician would be concerned about a certain policy’s impact on people’s well-being rather than its impact on the next set of polling data.

A sense of professional identity would also rein in politicians who act in their own narrow self-interest or with blind loyalty to a political party. Groups of professionals learn to police themselves against this temptation: It’s how they steward the institutions they serve.

Protecting the profession against cronyism through reform laws may be an important step, but professional identity goes beyond forced compliance and has the potential to bring honor back to the title “politician.” This would often involve crossing the aisle — e.g., Sens. John McCain, R-Ariz., and Ben Nelson, D-Neb., forming the Gang of 14 to avert a breakdown of Senate rules — and would always prioritize the good of the nation and its political institutions.

Like business, politics is too diverse a field to have a certification procedure like the bar exam. But there is a strong tradition of an oath, similar to the Hippocratic Oath for doctors, that says the politician will “preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States” — an expression of professional commitment too often forgotten, along with the ancient sense of honor in politics.

The problem with “career” politicians is not that they have too much experience — it’s that too many have forgotten how to maintain the balance of loyalty to citizens’ immediate needs and the nation’s long-term prosperity.