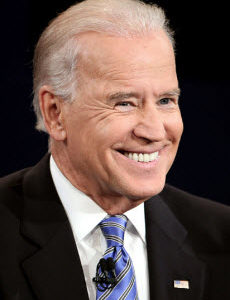

While 2020 Democratic contender Joe Biden hasn’t announced an official stance on hot-button tech issues like breaking up Big Tech or net neutrality, his privacy record may give Democrats pause.

Joe Biden’s record on privacy issues extends back to at least 1994 when, as a US Senator from Delaware, he introduced the Communications Assistance for Law Enforcement Act (CALEA). It required telecom carriers and manufacturers to design their equipment and services to ensure that they were accessible to surveillance by law enforcement. It was later expanded to cover broadband Internet and VoIP traffic.

CALEA also forces communications equipment manufacturers — like Apple, or Samsung — to hand over hardware and software designs to law enforcement with a warrant.

Privacy advocates often decry laws like this CALEA, arguing that they give the federal government too much discretion and leeway as to how, when and why it can intercept or extract American citizens’ communications.

After CALEA, Biden continued to push similar laws and policies.

In response to the Oklahoma City terrorist bombing in 1995, Biden introduced the Omnibus Counterterrorism Act of 1995. Congress never voted on the bill, but Biden said the controversial 2001 USA PATRIOT Act — which allows the FBI to wiretap and search American citizens’ phone calls, emails and financial records without a court order — copied his 1995 bill.

During the George W. Bush presidency, the issue of government surveillance became more partisan, and Biden walked back his views. In 2006, Biden joined his fellow Democrats in vehemently condemning surveillance policies of the Bush administration, comments that came back to haunt him when the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) juxtaposed them with comments from President Obama in 2013 defending his administration’s mass surveillance policies.

There are more examples of controversial, privacy-related legislation sponsored by Biden: in 1991, he introduced the Comprehensive Counterterrorism Act and the Violent Crime Control Act, both which included anti-encryption language that privacy advocates argued effectively banned encryption.

Phil Zimmerman, who created Pretty Good Privacy (PGP), an encryption program to secure communications, said he created PGP in response to Biden’s CALEA, the Comprehensive Counterterrorism Act, and the Violent Crime Control Act.

“[The Comprehensive Counterterrorism Act] would have forced manufacturers of secure communications equipment to insert special ‘trap doors’ in their products, so that the government could read anyone’s encrypted messages,” Zimmerman wrote. “It reads, ‘It is the sense of Congress that providers of electronic communications services and manufacturers of electronic communications service equipment shall ensure that communications systems permit the government to obtain the plain text contents of voice, data, and other communications when appropriately authorized by law.’ It was this bill that led me to publish PGP electronically for free that year, shortly before the measure was defeated after vigorous protests by civil libertarians and industry groups.”

According to Zimmerman, “If we do nothing, new technologies will give the government new automatic surveillance capabilities that Stalin could never have dreamed of. The only way to hold the line on privacy in the information age is strong cryptography.”

Given the Obama administration’s cozy relationship with Silicon Valley (Google, IBM and Microsoft were three of Obama’s top funders), Obama’s former vice president is unlikely to take a hardline stance on Big Tech, or to be sympathetic toward Congress’ efforts to create an effective federal privacy law.

Some industry observers describe Biden as a “net neutrality skeptic,” a notion reinforced when his first campaign event after entering the race was a fundraiser at the home of a Comcast lobbyist. While Biden didn’t take money from Silicon Valley as a senator — most of his funding came from law firms — his track record indicates he would likely follow in the footsteps of Bush and Obama when it comes to privacy issues.