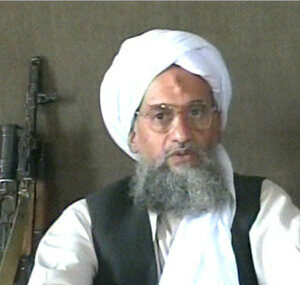

In a society governed by the rule of law, capturing and trying the intellectual force behind the 9/11 terror attacks, Ayman al-Zarahiri, would have been ideal but it was very unlikely. So kudos to the U.S. intelligence community under President Biden for doing the detailed work needed to locate a single individual among the millions of people in the Afghanistan/Pakistan region.

Eleven years ago, in 2011, the same intelligence community, under President Barack Obama, found then al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden living in Pakistan near a base of the U.S.-allied Pakistani military. In that instance, the American military killed bin Laden with a Special Forces raid; this time, Zawahiri was killed by Hellfire missiles fired from a U.S. drone.

However, the usual fist-pumping and chest-beating triumphalism surrounding such counterterrorist killings will likely drown out any discussion of the larger questions about the excessively grandiose U.S. foreign policy that motivated al-Qaeda’s 9/11 attacks in the first place and continues in the attenuated form today. To their credit, presidents Donald Trump and Joe Biden have indirectly raised questions about excessive interventions in the Middle East, which bin Laden, Zawahiri and al-Qaeda made very clear was their motivation for launching the 9/11 attacks and other successful strikes against American targets (for example, attacks against the U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania in 1998 and the USS Cole in 2000).

The American people, not much on historical introspection, never have wanted to hear such “unpatriotic” talk, especially with their understandable desire for revenge in the aftermath of the catastrophic 9/11 attacks, which killed nearly 3,000 American civilians. No excuse ever exists for such terrorism against innocents. But the U.S. government, after 9/11, should have at least privately taken notice of some of its own bumbling culpability for al-Qaeda’s potent retaliatory strike; and, after limited retaliation to quench a public thirst for retribution, brought a much lighter touch to the greater Middle East to reduce future motivation for Islamist radicals to strike U.S. targets.

Instead, then-President George W. Bush doubled down on the U.S. intervention in the Middle East that motivated al-Qaeda’s war on the United States in the first place. Instead of more limited retaliatory strikes against the al-Qaeda group, he chose to invade Afghanistan, take out the Taliban government, which was playing reluctant host to al-Qaeda, and then begin a long nation-building war that Biden ended two decades later. Even worse, Bush used public fear and furor over the 9/11 catastrophe to imply a false connection between al-Qaeda and Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein to carry out what seems to have been a personal vendetta against the Iraqi despot.

The unneeded invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq turned into U.S. occupations that predictably drove more retaliatory Islamist terrorism, in those countries and worldwide. In Iraq, al-Qaeda’s resistance to the U.S. occupation morphed into the virulent Islamic State group, which eventually took over large parts of Iraq and Syria until it was beaten down by even further U.S. military intervention.

The two-decade Afghan invasion and nation-building war and the long Iraq invasion, occupation and reinvasion were unnecessary, costly (in lives and trillions of dollars), and counterproductive ways to fight terrorism.

The efforts by the United States over time to painstakingly find and kill terrorists with Special Forces raids and drone strikes show that Biden’s over-the-horizon approach to terrorism may not be ideal, but it is workable and is much less inflammatory to Islamist jihadists than costly and counterproductive quagmires on the ground in the greater Middle East.