Democrats are clamoring for full disclosure of Judge Brett Kavanaugh’s documents—more than one million of them—from the judge’s time as a member of the George W. Bush White House team. Republicans are pushing back, threatening to hold the confirmation vote on the eve of the November midterms when it might do the most damage to red-state Democrats

To many Americans, the vetting process may appear petty and partisan. After all, Judge Kavanaugh’s held high-placed government jobs for decades. He was confirmed for the Federal Court of Appeals in 2006, and Democrats spent three years before that fighting to keep him off of it. At this point, most people wonder, what could possibly go wrong?

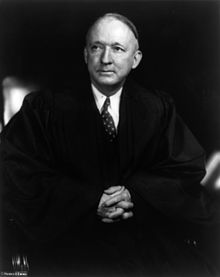

Meet Justice Hugo Black.

In the summer of 1937, elderly Associate Justice Willis Van Devanter announced his retirement, giving President Franklin Roosevelt his first SCOTUS nomination. (He ultimately appointed eight justices.)

Roosevelt was still smarting from his greatest political defeat, rejection of the Judiciary Reorganization Bill–better known as the Supreme Court packing bill. For FDR, the choice was a no-brainer. He quickly tapped 50-year-old Senator Hugo Black of Alabama. The Senate Judiciary Committee recommended approval.

When the nomination was announced, dark rumors about Black’s past began circulating on Capitol Hill. But most of his fellow senators, who’d known him for more than a decade, shrugged them off. Black’s appointment was approved by the full Senate the very next day in a 63-16 vote. Nomination to confirmation took only five days. Two days after that, Black resigned his Senate seat and sworn in as Associate Justice on August 19th. It had been remarkably smooth sailing.

Until the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette came out less than a month later with a bombshell headline:

“Justice Black Revealed As Ku Klux Klansman”

And it immediately hit the fan in Washington.

FDR tried to dance around the controversy. At a news conference the next day he told reporters, “I know only what I have read in the newspapers…Mr. Justice Black is abroad. Until such time as he returns there is no further comment to be made.” That bought a little time, but nothing more. In today’s terminology, the story had legs.

Black’s remarkably fast confirmation had people asking whether the process needed reforming. At the following week’s press conference, a reporter wanted to know if Roosevelt thought the Justice Department should “automatically” investigate all Supreme Court nominees. “No, certainly not,” FDR huffed. “A man’s private life is supposed to be his private life…”

That same day reporters caught up with Black who gave them what today sounds like a Trumpian response: “If I make any statement it will be in a way the people can hear me and understand what I have to say, and not have to depend on some parts of the press which might fail to report all I have to say.”

In other words, #FakeNews.

Black finally made his statement on October 1st in a coast-to-coast radio broadcast. In one of the very first uses of the new electronic mass medium for political survival, Black presented his case directly to the American people.

“I did join the Klan,” he admitted. “I later resigned and never rejoined…I have had nothing to do with it since that time. I abandoned it. I completely discontinued any association with the organization. I have never resumed it and never expect to do so.”

It turned out Black had joined the notorious secret society for purely political reasons. In many Southern and Midwestern states back in the day, a candidate for public office simply couldn’t be elected without its endorsement.

So when Black ran for the U. S. Senate in Alabama in 1926 he did what a lot of candidates did at the time: He asked for, and received, the Invisible Empire’s seal of approval. It’s believed he even made campaign speeches at several local Klan rallies around the state.

Once he was elected, it appears Black had no use for the Klan and dropped his association with it. And that’s essentially what he told listeners during his radio broadcast. A reported 50 million Americans tuned in, and they must have been satisfied with his explanation because the scandal quickly faded. With Hitler on the march in Europe and Japan casting lusty looks around the Pacific, there were plenty of other crises on deck to keep the public awake at night.

Black went on to serve 24 years on the high court. There was nothing in his record there to suggest he had once been a Klansman. For instance, he was among the unanimous vote in the landmark 1954 Brown v. Board of Education ruling that ended racial segregation in public schools.

In a final bit of irony, the same year he stepped down (1967) the Supreme Court received its first African-American Associate Justice, Thurgood Marshall. Things were forever changed. A Klansman would never be confirmed today, regardless how brief and casual his membership had been.

In his final years, Black repeatedly insisted joining the Klan had been a mistake. But not long before his 1971 death he also said, “I would have joined any group if it helped get me votes.”

No president since Roosevelt has ever wanted to experience that kind of unpleasant surprise ever again. And given the current level of scrutiny SCOTUS nominees receive—up to and including their penchant for baseball tickets—a Hugo Black moment is unlikely to happen again.