South Korea’s pursuit of a declaration that the Korean War is over is an exercise largely unknown to virtually all Americans aside from those with a stake in the debate. Ask just about any U.S. citizen if anyone’s waging war in Korea, and the response will be one of bewilderment. What war, what are you talking about, is there a war going on over there, are typical answers.

Of course, there is no war, but some people seem hellbent on convincing everyone the Americans and South Koreans are fighting the North Koreans and maybe the Chinese. Unless you’ve been following the discussion, which virtually no one I know has been doing aside from diplomats and think-tankers and activists, you won’t know or care. Often, talking to ordinary folk outside “the loop,” you have to explain, yes, we were waging war in Korea seven decades ago and, no, we don’t want to have to fight another war there.

That should end the conversation, other than maybe for a few questions from people who’ve seen the headlines about this crazy man in North Korea who persists in making big statements and showing off his toys, which happen to be nukes and missiles. Among most people, there’s no real concern that he’s going to fire anything or nuke anyone. Other issues make the headlines, led by President Joe Biden’s battle to get a divided Congress to legislate his multi-trillion dollar “Build Back Better” infrastructure and the struggle to convince anti-vaxxers of the need to get the jab.

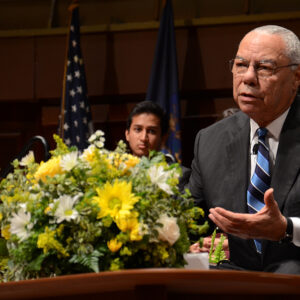

The death of Colin Powell, Vietnam War veteran, former chairman of the joint chiefs of the U.S. armed forces, former defense secretary, and former secretary of state, was a reminder of his level-headed view of Korea. South Korea had had only “limited success” in reaching out to North Korea, he said in a visit to Seoul in 2008. “You have to be firm with the North Koreans.”

That advice, if repeated today at either the Pentagon or State Department, would undoubtedly not be welcomed by South Korean leaders as they beseech the Americans to look for the magic password for drawing the North into dialog and above all to agree to a statement saying the war is over. What war, and why repeat the obvious, would be the response from the vast majority to whom the discussion is massively irrelevant.

Powell himself came close to asking the same question last year at a conference in Seoul marking seven decades since the opening months of the Korean War. On a link from the U.S., he said China would not stand for North Korea waging another Korean War and he wasn’t concerned about North Korean missile tests. Mercilessly, he berated Donald Trump, hot on the campaign trail for reelection as president, for demanding South Korea pay far more than seemed reasonable for having 28,500 U.S. troops on major bases in-country, and he praised the South for “what it’s done for its own people.”

Against his background as a military leader and diplomat, Powell was all in favor of dialog but not at the expense of concessions. His service as a battalion commander in Korea in the 1970s is almost overlooked in between his early days as an officer in Vietnam and his final posts at the Pentagon and State Department.

If Powell’s record is any guide, he would have encouraged dialog while sticking to demands for North Korea to show definite signs of giving up its nukes and missiles. “Listening to the other guy” did not mean bowing to intimidation.

Powell came to regret his speech at the UN in 2003 setting forth the phony rationale for invading Iraq for having weapons of mass destruction. Iraq under Saddam Hussein may not have had WMD as then-defense secretary Donald Rumsfeld claimed. But North Korea is a different story. Kim Jong Un boasts of his nukes and missiles, never more so than this week in an exhibition in Pyongyang.

Ignoring American entreaties for dialog, the North Koreans are betting the South Koreans will be urging the U.S. to compromise on principles. Powell as a soldier/diplomat would have stood up against pressures from the South as well as the North. If South Korea’s President Moon Jae-in wants to sign a declaration declaring the Korean War is over, fine, but the Americans don’t have to be a signatory to such a meaningless document.