The vast ocean of mineral wealth lying beneath New Mexicans’ feet holds the promise of lucrative jobs and abundant tax revenue.

But all that copper, gold, zinc, lead, uranium, and molybdenum is not to be touched. Because while your phone and tablet and laptop might tell you it’s 2019, it’s actually 1926.

Well, at least to the state’s “environmentalists,” Calvin Coolidge is in the White House, Eddie Cantor’s performing on Broadway, and Jack Dempsey is the heavyweight champ.

The New Mexico Wilderness Alliance, in opposing Comexico LLC’s proposal to conduct mineral exploration in the Pecos/Las Vegas Ranger District of the Santa Fe National Forest, thunders that back in the 1920s, the “Pecos Mine was not closed down responsibly, leading to the contamination of soils, 5-10 acres of wetlands, Willow Creek and the Pecos River.” The organization, and its allies in the state’s deep-pocketed army of professional alarmists, are distributing a petition, to let the proper authorities know that “you oppose an international drilling company drilling near the Pecos Wilderness!”

Yes. Ninety-three years ago, environmental statutes, rules, and enforcement mechanisms at the local, state, and federal levels were not up to 21st century standards.

So what?

It’s not 1926 anymore, and the murder board of environmental hoop-jumping that mining companies must face in order to extract useful stuff from the ground is truly dizzying.

During a recent permitting inspection — it lasted 13 hours — Comexico staffers traveled to the proposed exploration site with bureaucrats from the Mining and Minerals Division and Forestry Division of the New Mexico Energy, Minerals and Natural Resources Department, the New Mexico Environment Department, the New Mexico Department of Game and Fish, the New Mexico Office of the State Engineer, the U.S. Forest Service, and Santa Fe County. (No one from the New Mexico Department of Cultural Affairs could make it — this time.)

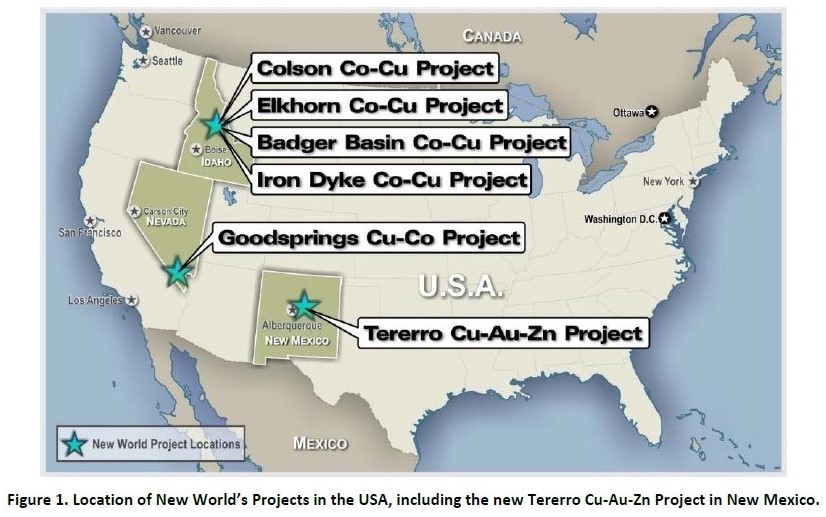

Comexico’s interested in the “middle-Proterozoic-aged volcanic massive sulphide” deposit because it contains copper, gold, and zinc. The managing director of the LLC’s parent, New World Cobalt — to the New Mexico Wilderness Alliance’s profound worry, the corporation is based in Australia — called the site “a fantastic, low-cost opportunity,” with such richness “very hard to come by globally.” (And when one is found, it “can generate extraordinary value over a long period of time.”) Plus, an “interstate highway and a national railway line both pass approximately 20km to the south,” and a “sealed road provides access from the interstate highway to within approximately 5km of the Deposit.”

Before Comexico gets to the loot, it must survive far more than a site inspection. No exploration activities will be allowed without the state’s by-your-leave. No extraction will commence before the company meets the ludicrously stringent requirements of the National Environmental Policy Act. Air, water, plants, animals, public health/safety, transportation, “social, cultural, and economic resources” — the list of items to be assessed is bottomless. And public comments, either submitted in writing or made at public hearings, will offer anti-mining activists platforms to tell regulators why Comexico is a dirty, rotten land-defiler, and shouldn’t be allowed to disturb a square millimeter of the Santa Fe National Forest.

But why wait for the professionals to do their evaluations? The governor’s already decided that Comexico isn’t welcome. In a letter to the U.S. Forest Service’s chief, Michelle Lujan Grisham expressed her “opposition to plans to begin mining exploration in the Upper Pecos Valley.” Unsurprisingly, she took a trip down past-pollution lane, lecturing that previous mining activities “contaminated the Pecos River and spread toxic mine waste materials all through the valley.”

All liability, no asset. Left unmentioned in the governor’s screed is the employment Comexico would bring to a state in desperate need of a non-petroleum-related jobs boost. Whether it’s engineers or inspectors or equipment operators, the mining industry pays wages well above the New Mexico median.

Harvest a dense vein of copper, gold, and zinc in a remote forest outside Santa Fe? No way.

Reopen Sierra County’s Copper Flat Mine? Come at me, bro.

Shift the Mount Taylor Mine’s status back to “active,” allowing the potential for resumed uranium extraction in western New Mexico? Unthinkable.

Hoarding New Mexico’s mineral horde, based on demonstrably false notions of inadequate environmental protection, denies the Land of Enchantment a powerful economic-development opportunity — one that is far more sustainable than begging Washington for more “public investments.” But to tap its motherlode, the state needs elected officials unwilling to kowtow to “green” hysterics, and a populace able to understand that it’s not 1926 anymore.