The month of April will be the among the most challenging months in American history.

The physical, mental and emotional well-being of the nation is at hope’s edge, as our nation comes to grips with a global pandemic and dire economic consequences.

For many mass shooting survivors and their communities, though, April is challenging for another reason: The five days between April 15-20 have been notoriously marked with the intentional spilling of innocent blood.

On April 15, 2013, terrorists killed six and seriously injured 280 in the Boston Marathon attack. April 16, 2007, was the school shooting at Virginia Tech University.

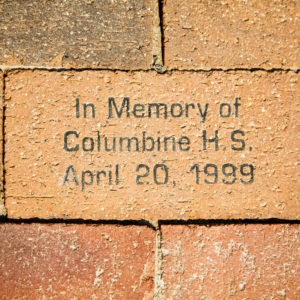

On April 19, 1995, a mass murderer killed 168 innocent victims and seriously wounded more than 680 in the Oklahoma City bombing. And on April 20, 1999, there were the murders of 15 at Columbine High School in Colorado.

The connection between the April dates is no coincidence. Sadly, several killers sought to “outdo” the massacres that preceded their carnage and there exists a link between a series of massacres occurring in April, and the selection of massacre dates to coincide with the massacre anniversaries.

It starts with April 19, 1993, the date law enforcement officials raided a compound near Waco, Texas, resulting in a lengthy standoff and 86 fatalities.

Next, the two terrorists at Oklahoma City who drove a truck-bomb to the Murrah Federal Office Building selected the Waco anniversary; two years later, on April 19, 1995, they conducted a terrorist assault that killed 168 people.

Then, with a goal of killing more people than the terrorists did at Oklahoma City, the two school shooters at Columbine High School picked April 19 for their massacre — postponed by an unknown reason to April 20.

On April 20, 1999, the two high school boys murdered 15 innocent students and teachers, seriously injuring many more.

The tragedy at Columbine, then, took on great importance for several rampagers who followed them. Killers at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Connecticut and Virginia Tech studied and obsessed over Columbine, as did many others.

How do communities, victims and survivors deal with the aftermath of mass shootings?

In my book, “After the Bloodbath: Is Healing Possible in the Wake of Rampage Shootings?,” I examine the aftermath of mass shootings and compare community and legal responses to responses in indigenous communities, with special attention devoted to restorative and therapeutic justice.

I compare the aftermath of several shootings with a fatal massacre that occurred in March 2005 at the Red Lake High School on the reservation of the Red Lake Band of Chippewa Indians in northern Minnesota.

For example, at Red Lake, in contrast with other massacres like Newtown, the family of the killer did not have any difficulty finding a place to bury the shooter, and the killer was given a traditional funeral and mourning rituals, which were well attended.

Just as in Newtown, at Red Lake, a family member, the shooter’s grandfather, was the first victim, and like Newtown, access to the guns used could be attributed to the family member.

Yet, at Red Lake the shooter’s grandfather was counted as a victim and, in contrast to many other rampages, not blamed for the killings. The grandfather was given a hero’s funeral which was very well attended.

What was most remarkable, though, was that the tribe included the killer’s family in distribution of victim compensation funds, helping to pay for his funeral expenses.

In Red Lake, parents of victims thought the murderer deserved some recognition from the community so he would not, as a human being, be forgotten.

A number victims’ relatives forgave the killer and considered the circumstances preceding the massacre.

There are more than 500 American Indian tribes in the United States and more than 200 tribal court systems.

Indigenous peoples have a long history of restorative practices and engage in something called “peacemaking courts,” where they invite in elders, relatives and spiritual leaders and move toward restoring social bonds and healing the frayed social fabric.

There are more lessons we can take from how indigenous peoples deal with mass shootings. Parents and family members of mass murderers, typically mourning as well, should be given empathy and, at a minimum, not treated as community pariahs.

While the world struggles in April to deal with the very real public health emergency, community cohesiveness, kindness and empathy are at a premium.

The festering wounds associated with the still unresolved public health threat surrounding mass shootings, the linked suicide crisis, and a long list of suffering survivors will be painful throughout the month.

We have a lot to do to heal our planet.