Bill Richardson could teach Donald Trump something about the art of the deal.

He has done a lot of them. Richardson also wrote a book about the art of the deal, the big deal, titled “How to Sweet-Talk a Shark; Strategies and Stories from a Master Negotiator.”

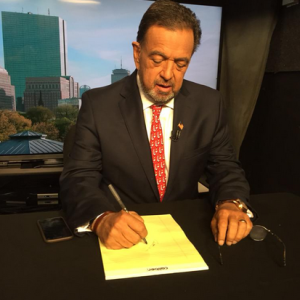

In a towering life of public service (U.S. representative, U.N. ambassador, secretary of Energy, New Mexico governor and peripatetic hostage negotiator), Richardson confronted Fidel Castro, Saddam Hussein, the Taliban, two of North Korea’s dictators, and an assortment of international thugs. He was a five-time nominee for the Nobel Peace Prize.

The essence of Richardson’s deal-making was that the commitment must be kept by both parties.

At present Richardson sees one of his deals in jeopardy, and he was in Washington last week to raise the alarm, meeting privately with former colleagues and appearing at a news conference at the National Press Club.

The deal in jeopardy involves a commitment he made, when he was secretary of energy in the Clinton administration, with the Russians to dispose of weapons-grade plutonium, the long-lived ingredient in nuclear weapons. There are 34-metric tons of the stuff that the United States is bound, by treaty with Russia, to dispose by integrating it into nuclear fuel and burning it in civilian power plants. This is known as mixed oxide fuel, or MOX.

But the Obama administration wants to end the program, before a fleck of plutonium has been processed for fuel. It is seeking to pull the plug on the construction of the facility at a Department of Energy site on the Savannah River in South Carolina, which is two-thirds complete and has already cost more than $4 billion.

The administration is now looking not at the completion cost, but at the lifetime cost of the facility. And it is saying that it is too high; although that could have been calculated years ago.

The deal was signed by Vice President Al Gore with Russia back in 2000. The Russians, for their part, are burning their surplus plutonium in fast reactors, which we do not have in operation.

The backstory may be not about lifetime cost, but about the deployment of federal dollars in the very near future. Nuclear industry insiders believe that the Department of Energy, which makes nuclear weapons and stockpiles them, wants to divert all available resources to its weapons refurbishment program and, in argot of the moment, kick the plutonium can down the road. New funds are harder to come by than re-purposing extant ones.

The department is floating the idea that the plutonium should be “down-blended,” meaning mixed with some secret ingredient that the department believes will render it safe for all time, and stored in a troubled existing facility: the Waste Isolation Pilot Project in New Mexico.

“I don’t believe this is a good course of action.” Richardson told reporters at the Press Club event. He said the WIPP facility was designed for low-level waste … there would be a lot of opposition in New Mexico.” He was involved in that project, too, when he was in government.

On sanctity of treaties, Richardson said, “I think that (closing down the MOX facility) would be a grave mistake across the board.”

Richardson said that he had negotiated with the Russians as U.N. ambassador and as energy secretary. In the matter of plutonium disposal, he said the Russians have kept their side of the deal. There was plenty of tension over Ukraine and Syria, and “we don’t need any more tension.” He said, “This is one potential area of cooperation that should not be discarded, and it would be, should the MOX facility be discarded.”

If the MOX facility is shuttered, it will be one of many nuclear facilities across the country, paid for by taxpayers, that have been abandoned because of other priorities or political agendas. The price is high in enthusiasm, creativity and commitment from the workforce at facilities, like the MOX one.

The dollars spent have no legacy except a sad, new kind of national monument: structures that have been left forlorn and incomplete as politics have zigged and zagged. These abandoned structures range from the experimental Fast Flux Test Facility in Hanford, Wash., to the Integrated Fast Reactor in Idaho Falls, Idaho, to the sad, $18 billion Yucca Mountain facility sitting unused in Nevada. There are many more.

As Richardson might tell, in a long life in public service, you have to defend the deal long after it was signed, sealed and delivered. Not so, perhaps, in real estate transactions.