On a daily basis we can find in the news myriad studies and reports attempting to explain the elusive millennial—our habits, beliefs, economic prospects, voting patterns—you name it. But from this we get contradictory claims and more confusion.

“Millennials” are roughly defined as the generation born between 1980 and 2000. But my life experience as a 30-year-old millennial is much different than that of a 25-year-old, and that 25-year-old sees the world differently than a 20-year-old. We’re not simply a single generation as others before us.

There are two root causes of this. The first separation is 9/11. As a junior in high school, that day remains a vivid memory for me. But for a “millennial” who was in kindergarten at the time, the knowledge is most likely a second-hand history lesson.

The second divider of the millennial generation is the Internet.

April 30 was the 20th anniversary of decommissioning the National Science Foundation Network (NSFNET), and thus marked the birth of the commercial Internet.

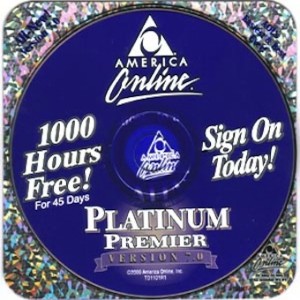

On the eve of this “Internet Independence Day,” I sat talking to a 26-year-old friend, only four years younger than me, about how much the Internet has changed since 1995. I mentioned America Online—the gateway that initially welcomed so many of us to the online world. She asked if I meant “AOL Instant Messenger.” No, I responded, and then offered an explanation.

I would “Sign On” and my 56Kbps dial-up modem would screech. Once connected, before me lie a very-limited set of choices. There were channels like “News Stand”, “Reference Desk”, and “Personal Finance”. I frequented the “Kids Only” section, and I occasionally used the Teacher Pager to get a little homework help. Inevitably, I would be close to getting the answer when someone would accidentally pick up the phone and I’d be disconnected, losing my progress. “Should I log back on?” I wondered. One had to keep track of their time online as exceeding five hours a month would incur extra fees.

Amidst the channels, there was also “Internet Connection”. That one was confusing for your average America Online user. “FTP”, “World Wide Web”, “News Groups”, “Gopher & WAIS” – these were the menu options if you clicked there. Google did not exist. If you wanted to browse the Web, you pretty much needed to know where you wanted to go. You could buy a physical Yellow Pages for this purpose. And best to get that from a physical bookstore since Amazon was still in its infancy.

But then the Internet grew exponentially.

The government stayed out of the way to allow growth of the online world and broadband connections.

A new first-of-its-kind study from Stuart Brotman of Harvard Law School and The Media Institute points to the light regulatory approach helping to develop “net vitality” in the United States. America Online became a relic, superfluous in the new world. As time passed, innovation and irrational exuberance brought us the dotcom bubble and bust, but rising from the rubble were companies like Google and Amazon. Apple had a resurgence. Then came Web 2.0 and the user-generated content of sites like Facebook and Wikipedia. More innovation is to come.

In commemoration of Internet Independence Day, a group called Tech Innovators, which includes VoIP creator Jeff Pulver, Dallas Mavericks Owner Mark Cuban and Grateful Dead lyricist John Perry Barlow, hosted an event in the nation’s capital. Speaking at the reception were several policy leaders from the Clinton Administration who fought against domestic and international efforts to tax and regulate the Internet. Each was convinced of how different the world would be today had the Internet not been free to commercialize and innovate.

I experienced the world without the Internet and have been part of the online world for each of the succeeding eras. Others who are also termed millennials are unlikely to recall a life sans YouTube. We now live at a time where we lack a shared experience with many outside of our immediate age cohort. Millennials are not a single generation. Such has been the power of a free and open Internet.

If millennials are confounding to earlier generations, it is because there has been a paradigm shift. We are only a single generation in the sense that we have lived through an era where government has allowed technology to flourish. In that sense, perhaps there should not be an endpoint to the millennial generation. Millennials and the age of innovation may continue on if we can hold back an ever-eager government from instituting a strong regulatory hand.