The chaos, confusion, and embarrassment that is unfolding in our withdrawal from Afghanistan are starkly reminiscent of President Lyndon Baines Johnson’s Vietnam decision-making. It has been chronicled by experts in groupthink. According to the late Irving Janis who coined the term, groupthink refers to a mode of thinking by people whose investment in a cohesive group and “strivings for unanimity overrides their motivation to realistically appraise alternative courses of action.”

There is an abundance of evidence that Johnson did not encourage or tolerate discussions that ran counter to his views of how to run the war in Vietnam. As a result, candor was at a premium and people like Under Secretary of State George Ball were shunted aside because they weren’t team players.

Contrast the Johnson decision-making process with what happened after the Bay of Pigs disaster. President John F. Kennedy’s decision-making process gave free and open discussion and debate of options and contingencies. He worked the problem until the best approach emerged. As a result, his management of the Cuban Missile crisis is considered a model of effective crisis management.

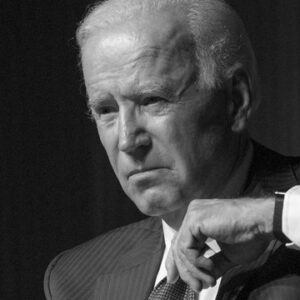

There have been reports that Biden is a bit stubborn and does not encourage advisors to challenge and debate his perspective. If that is true, it goes a long way to explain all that has gone wrong in ending our engagement in Afghanistan. It is inconceivable the secretary of defense and chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff did not tell him his preferred course of action was very risky. How else can you explain a process that turned the removal of Americans and Afghans who had helped us into the major evacuation that is now taking place? Claiming the efficiency of the evacuation process demonstrates that the August 31 exit deadline, over the objections of our NATO allies, was justified and correct is a weak attempt at face-saving.

Anyone who knows anything about military and contingency planning would have advised the president against setting an arbitrary exit date. A well-developed plan would have begun by removing Americans and Afghan nationals who worked closely with our military personnel. Once non-combatants were in the process of being removed, our armed forces could have been used to slow the rapid Taliban takeover of provinces, then turned to the withdrawal of troops and equipment. That so much U.S. equipment has fallen into the hands of the Taliban is both inexcusable and further evidence of a botched plan.

No one should have been surprised when the Afghan army gave up and ran for the hills once U.S. forces began to leave. Assuming loyalty to the Kabul government instead of to their tribal warlords had to be a very questionable assumption. Indeed, the failure to build a stable government over the period of 20 years should have been a strong warning that ending this war was going to be very complex and that a hard-headed and thorough vetting of options was essential.

Scholars will make a lot of money writing about the Afghanistan debacle. In the end, this sorry chapter in national security decision-making will almost certainly be another validation of the groupthink concept. The late historian Barbara Tuchman in “The March of Folly” described “wooden-headedness as “assessing a situation in terms of preconceived fixed notions while ignoring or rejecting any contrary signs. It is acting according to wish while not allowing oneself to be deflected by the facts.”

Instead of continuing to be wooden-headed and using political spin that the Afghanistan debacle is actually an example of political courage, Biden should, as Kennedy did in April 1961, tell the truth: “There’s an old saying that victory has 100 fathers and defeat is an orphan…I’ve said as much as I feel can be usefully said by me in regard to the events of the past few days. Further statements, detailed discussions, are not to conceal responsibility, because I’m the responsible officer of the government …”

If he followed Kennedy’s example his poll numbers would almost certainly show a dramatic increase.