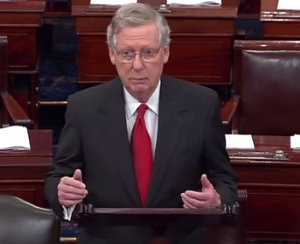

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell sparked outrage when he told the folks back home what Republicans would do if a Supreme Court seat becomes vacant next year: “Oh, we’d fill it.”

“Remember Merrick Garland!” has been the Democrats’ battle cry ever since Senate Republicans refused to consider then-President Barack Obama’s Supreme Court nominee to replace Antonin Scalia in 2016. McConnell argued at the time it was an election year and the people should decide who they want to fill the seat.

Hypocrisy? There is certainly plenty of that to go around when it comes to partisans and judicial confirmation politics, and neither side is wholly blameless. From blue slips to filibusters and nuclear options, senators have left no procedural stone unturned when trying to slow-walk opposing nominees. But the fact is, Obama had every right under the Constitution to nominate Garland — and the Republican majority in the Senate had every right to block him.

The same would be true if the roles were reversed — a Republican president and a Democratic Senate — and the same GOP majority is well within its constitutional purview to approve a nominee sent to them by President Donald Trump.

This isn’t just about partisan politics. The Supreme Court now has more to say about abortion, gun control, affirmative action, religious liberty and a host of other important policy issues than any five senators. As long as that’s the case, the parties are doing their duty to their voters when they treat a court vacancy the same way they would treat an open Senate seat — especially one that would decide the majority.

If you care about the issues the Supreme Court decides, then you have at least as much stake in its majority as you do in which party controls the Senate.

Democrats actually began taking this fact seriously before Republicans did. They only allowed Anthony Kennedy — who in 1992 wrote the decision upholding Roe v. Wade — onto the Supreme Court after voting down Robert Bork and forcing the withdrawal of Douglas Ginsburg. Only 10 Democrats voted for Clarence Thomas. Half the Democrats in the Senate voted against John Roberts. Only four voted for Samuel Alito, who was nearly filibustered, three for Neil Gorsuch, and one for Brett Kavanaugh.

You have to go all the way back to Antonin Scalia in 1986 to find a time when Democrats supported a staunch conservative’s nomination to the Supreme Court, no matter how qualified. And even then, that was partly because some Democrats were focused on preventing the promotion of William Rehnquist to chief justice.

Even after Bork and the near-Borking of Thomas, only three Republicans voted against confirming Ruth Bader Ginsburg and just nine voted against Stephen Breyer. The overwhelming majority of Republican senators approved both of Bill Clinton’s Supreme Court picks.

It was actually under a Republican president that GOP senators first took a strong stand, demanding George W. Bush withdraw Harriet Miers in favor of someone better credentialed and more reliably conservative.

Earl Warren, Harry Blackmun, John Paul Stevens, David Souter — some of the most liberal justices were actually appointed by Republican presidents. You have to go all the way back to Byron White in 1962 to find a conservative put there by a Democrat. Conservatives have since worked to correct that imbalance while also opposing more Democratic nominees.

Republicans campaigned in 2016 risking the consequences of keeping Obama’s choice of Garland off the Supreme Court, with Democrats promising to confirm him. If Republicans confirm a third Trump high court nominee next year, the voters will once again get to make the final verdict. Voters also understand their preferred policy outcomes could be riding on whether the liberal or conservative justices are in the majority.

Preventing Garland from receiving so much as a hearing is at least as constitutionally defensible, and less a violation of political norms, than many of the court-packing schemes being entertained by 2020 Democratic presidential candidates. Both parties have played a role in escalating the judicial confirmation wars.

A case could certainly be made that it would be better if Democrats voted for qualified conservatives and Republicans for qualified liberals, like in the days of Scalia and Ginsburg, much as the country might profit from the Supreme Court ceasing to be a national abortion policy-making body.

But as Mitch McConnell realizes, that is not the situation in which we now find ourselves. Those old conventions can be restored only if both parties abide by them. Don’t expect that to happen anytime soon.