Having had a parent who struggled with diminished hearing for decades, I have seen first-hand how hearing challenges can impact a person. My father contracted a disease as a child and one of its effects was the loss of hearing in one ear. Consequently, he struggled with hearing loss for his entire life. My father was not alone in dealing with the challenges of hearing loss. Thousands of Americans struggle with their hearing, which makes access to hearing aids an increasingly important issue in this country.

I enthusiastically applaud Congress and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for taking steps to make hearing aids available over the counter for adults with mild-to-moderate hearing loss. That is a tremendous and much-needed step, particularly for older persons of modest means and a fixed income, for whom hearing aids may be unaffordable. The FDA, though, shouldn’t rush to open the marketplace for these over-the-counter devices until they take action to ensure they are safe and won’t do permanent damage to those they aspire to help.

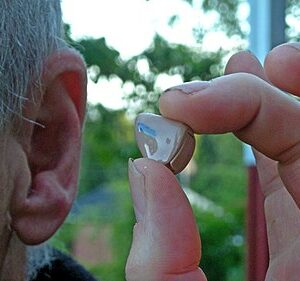

There is room for improvement, though, in the FDA’s guidelines. Thanks to his employer-sponsored health coverage, my dad was fitted for hearing aids in his fifties. As much as they benefited him, they became more difficult to manage as he grew older. Finding the sweet spot in the volume control was a constant challenge, and it was not unusual to hear a loud high-pitch squelch when he adjusted the volume in his ear.

We were never too concerned, though, because my dad’s hearing aids were prescribed by a hearing care professional who was available to help him correct any problem. We are about to enter a new world when hearing aids are sold over-the-counter without the consult of a professional first. By removing that layer of professional medical protection, the need for strong regulatory safeguards increases. Unfortunately, the FDA’s proposed rules for over-the-counter hearing aids fall short of what consumers with mild-to-moderate hearing loss are going to need.

Essentially, the FDA’s first draft regulations treat hearing aids – which most users will wear for eight to 10 hours a day – by the same standards as commercial earbuds through which a jogger might listen to music for an hour or less. The FDA has set a top output limit (the maximum level of sound that goes into the user’s ear) for over-the-counter devices of 115 to 120 dB. This is higher than the 110 dB recommended for OTC hearing aids by the nation’s top associations of hearing care professionals and significantly higher than the 95 dB suggested by the World Health Organization for personal sound amplification products. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, exposure to sounds at 120dB can quickly cause hearing damage, and a publication by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health has suggested exposure to this level of sound is dangerous in as little as nine seconds.

The FDA’s response to this? Its proposed rules say over-the-counter hearing aid users will have 28 seconds to react and remove the devices if they feel hearing damage is imminent.

In the latter years of his life, my father’s mind was clouded by dementia. There was very little chance he would have realized he was endangering his hearing, much less be able to take remedial action in less than half a minute. That is, unfortunately, going to be the case for many consumers who buy a set of OTC hearing aids at their local drugstore. These consumers will tend to be older, and a significant percentage may have dexterity or cognitive challenges. Additionally, many will not have consulted a hearing specialist to even understand that a particular level of sound output is potentially dangerous.

The solution is simple. Apply safer limits for output and gain (the amount of amplification of outside sound by the hearing aid) that are consistent with the recommendation of the country’s top hearing care professionals. Here, a maximum output of 110 dB SPL and gain limit of 25 dB is more appropriate and strongly recommended. It is great that people with mild-to-moderate hearing loss and modest finances will have access to affordable hearing aids, but it should not come at the risk of causing increased permanent hearing damage, even if the retail price tag is a really good deal.