Pondering the future requires an extrapolation from a data point in the present. But different data points give very different futures. Beware of the prognosticators.

Take this as a data point: Stephen Entin, senior fellow at the Tax Foundation, a think tank devoted to tax studies since 1937, predicts that with an aging population and low birthrates, we’re going to need more immigrants to fill the federal and state coffers with their taxes. We’re also going to need hundreds of thousands of workers for health care and aged care in the years ahead, he says.

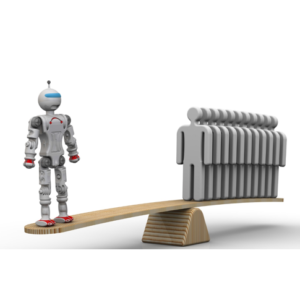

Or take this as a data point: MIT Sloan Professor Tom Kochan fears that artificial intelligence will substitute for millions of employees. Retraining is possible, but can you see a long-haul truck driver pushing wheelchairs in an assisted-living facility? Not easily.

Upheaval in work is the most predictable aspect of the future.

It is, if you will, already arriving in the workplace. New techniques and new concepts of what is work are afoot.

The old concept is that a person leaves school, gets a job and signs on to the social/work contract — gets company-paid benefits and expects security and stability. The infrastructure of society pointed the way to employer-employee model.

The new concept is the gig economy, where contract work and freelancing rule. The work/social infrastructure where medical insurance, Social Security and retirement are part of the deal is dying. But a one has yet to emerge in concept and in law.

Business is in the throes of its own future adjustment. Take 3D printing, more correctly called additive manufacturing. What was novelty a decade ago is now a tool used in industrial plants across the country. Instead of taking a chunk of metal, say aluminum, and cutting and lathing it to make a part, which wasted most of the metal, there’s no waste with 3D printing.

Now to make a part, you print it from metal powder to a design lodged in a computer. The saving in material, shipping and manpower is enormous.

And additive manufacturing, just like everything else on the shop floor, can be automated. Machines can sinter — the term for 3D printing — through the night with only artificial intelligence supervision.

There’s a new existential worry in every large enterprise in the United States, from banking to manufacturing, from electricity generation to hospital management and from building crane operation to pharmaceutical design: cyber-vulnerability.

To paraphrase Leon Trotsky, you may not be interested in cyber-war, but cyber-war is interested in you.

I’ve interviewed widely on the subject, from top academics to some of the most successful cyber-security entrepreneurs, to National Security Agency sources. The story is the same everywhere: Nothing connected to computers is entirely safe; and if it’s safe today, will it be tomorrow? That plague, like the plagues of old, will, I’m assured, be with us for decades, if not centuries to come.

Cyber-defenders build, cyber-hackers build around. It’s a version of what one secretary of defense, Harold Brown, said about the Soviet threat in the Cold War: “We build, they build.”

The changes are all around the home: Everything has changed since the day of the black AT&T phone, but you haven’t seen anything yet. Your packages may be delivered by drone, your phone service will be entirely mobile, and your life will be dictated by electronic secretarial aids. Alexa is just the beginning. With artificial intelligence, these robots will talk back to us and maybe argue, shudder the thought.

I pity the dogs. We had a dog that would be very upset if she heard my wife, a talk show regular, on the television when she was also elsewhere in the house. Dogs are sensitive to these things.

What if man’s best friend, eternal unquestioning companion, develops a strong affection for the electronic assistant and changes loyalties, especially if the gadget is feeding the dog? Will it be as Julius Caesar might have said, “Et tu, Fido?”