A New York Times reporter who said the oil and gas industry is linked to white supremacy is still on the energy sector beat, despite complaints she can’t provide objective coverage, emails obtained by InsideSources show.

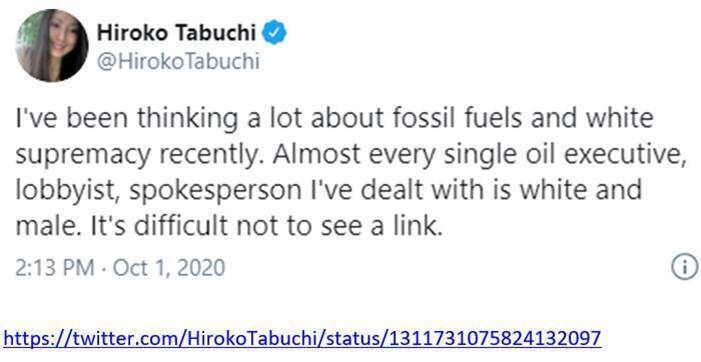

“I’ve been thinking a lot about fossil fuels and white supremacy recently,” Times climate change reporter Hiroko Tabuchi tweeted on Oct. 1. “Almost every single oil executive, lobbyist, spokesperson I’ve dealt with is white and male. It’s difficult not to see the link.”

One day after the tweet, a top executive with the American Petroleum Institute emailed Times climate editor Hannah Fairfield, who in turn tried to allay their concerns.

“We agree that the tweets you cited were overly opinionated,” Fairfield said to the executive. “Hiroko herself made the decision to delete them from her account. However, we are confident that her reporting on the industry has been accurate and fair, and has adhered to the high journalistic standards of the New York Times.”

Times executive editor Dean Baquet added in a subsequent email that he and other “senior editors” had consulted with Fairfield about the response. “We believe strongly that we have taken appropriate steps,” Baquet said.

However, there is no indication that the New York Times has taken any steps. Tabuchi is still covering the petroleum industry for the paper.

“I am at a loss in justifying to our executives why we would engage with a reporter who believes our entire industry and its executives are linked to white supremacy, something we strongly denounce,” the API official fired back to Baquet in response.

The official’s name was blacked out in the emails provided to InsideSources by a source close to the matter who requested anonymity because they were not authorized to divulge the emails or speak on the subject.

The API official added that allowing Tabuchi to simply delete the tweet without any correction or apology was “insufficient” and that Tabuchi’s comments were “in direct violation of your own handbook on ethical journalism.”

“Your institution is too good to look the other way on such a blatant lack of professionalism and neutrality,” he continued. “She has lost the confidence of our organization and I imagine any reader who views her troubling comments.”

An online version of the Times handbook for journalists says, “Staff members are free to discuss their own activities in public, provided their comments do not create an impression that they lack journalistic impartiality or speak for The Times.”

A request for comment from the Times was not returned.

Officials with API tell InsideSources they are still under the impression that no further disciplinary action has been taken.

“The reporter’s comments were deeply offensive and downright wrong about our industry,” said API’s senior vice president of communications Megan Bloomgren.

“We immediately raised the reporter’s comments to the highest levels of the New York Times since they directly violated the paper’s handbook on ethical journalism, and while we exchanged emails and had a meaningful discussion, the copy editing team took no action. Deleting tweets doesn’t delete inherent bias.”

When journalists delete tweets, they often publish an explanation for the deletion. But no such tweet appears to have been sent from Tabuchi to her more than 126,000 followers. Her current Twitter timeline only goes back to September 21, indicating she’s deleted her previous posts.

The simmering controversy over Tabuchi’s tweet illustrates how the social justice issue is being injected into the oil and gas debate as the country is grappling with questions of race and fairness after a summer of protests.

“Police violence and pollution are more connected than you might realize,” Tabuchi said in a since-deleted tweet from September. “This investigation documents how the fossil fuel industry finances police groups in major U.S. cities, while polluting majority Black and brown communities.”

In another deleted tweet, Tabuchi quoted an environmental activist who said, “Fossil fuel facilities are disproportionately — let me say that again, disproportionately — located in communities of color. From southwest Detroit to Baytown, Texas to Cancer Alley in Louisiana, communities of color are in the crosshairs of this pollution.”

Pennsylvania is a top natural gas producer in the country, especially as hydraulic fracturing technologies — usually called “fracking — have come to dominate the field and have unleashed a decade of new productivity for the industry. A 2017 study by API estimated that Pennsylvania is home to 322,600 fracking jobs.