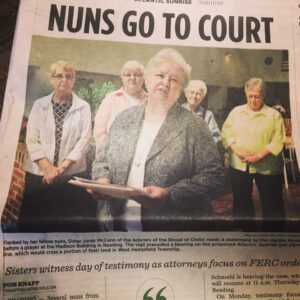

The press labeled them “Renegade Nuns,” a group of 16 Catholic Sisters in Lancaster, Pa. protesting in 2017 to keep an energy pipeline out of their cornfield. Members of the Adorers of the Blood of Christ international congregation, they become a media sensation, making headlines from Pittsburgh to Paris and attracting TV news crews from across the country.

And the nuns gave them plenty of news to cover. In their attempts to stop the Atlantic Sunrise Pipeline, protesters threw a pipeline dance party during a snowstorm as hardhat-wearing workers looked on. They held a “kayaction” event — using kayaks to deliver pizza. And, in hopes of injecting religious liberty legal issues into their lawsuits, the Sisters built a makeshift chapel in the middle of their cornfield and declared the pipeline’s path a place of worship.

In the end, their prayers went unanswered. The Williams Company completed its expansion of the existing Transco natural gas pipeline to connect Marcellus Gas Suppliers with markets in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern U.S. For three years, the gas has been flowing beneath the feet of families in Clinton, Columbia, Lancaster, Lebanon, Luzerne, Lycoming, Northumberland, Schuylkill, Susquehanna, and Wyoming Counties.

In the end, their prayers went unanswered. The Williams Company completed its expansion of the existing Transco natural gas pipeline to connect Marcellus Gas Suppliers with markets in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern U.S. For three years, the gas has been flowing beneath the feet of families in Clinton, Columbia, Lancaster, Lebanon, Luzerne, Lycoming, Northumberland, Schuylkill, Susquehanna, and Wyoming Counties.

But if you aren’t a target of the nuns’ ongoing litigation, you’d never know it. After months of tumult and media attention, the pipeline is largely forgotten. The nuns claim it’s causing spiritual damage to Mother Earth, but from a convenience, community, and environmental standpoint, the pipeline’s presence is entirely unnoticed.

“The pipeline is up and running and has been for some time now without incident,” says Tom Shepstone, a natural gas supporter and business management consultant in Honesdale, Pa. Gas began flowing through the pipeline on October 6, 2018. “The Atlantic Sunrise is really an important connection for the entire East Coast because it delivers Marcellus Shale gas to urban areas and then connects to other lines so that you can feed the whole urban population along the East Coast.”

Supporters of Pennsylvania’s energy sector say the story of the Atlantic Sunrise pipeline is typical for the industry. During the inconvenience of a pipeline’s installation, tensions run high and the public anger is real. But once the project is completed, the grass is re-planted and the streets are re-paved, people quickly move on.

In fact, local residents Delaware Valley Journal spoke to were surprised to learn the nuns were still fighting to shut down the project.

The Sisters, along with a group known as Lancaster Against Pipelines, say while the damages can’t be seen in the material world,

The makeshift chapel created by the The Adorers of the Blood of Christ in hopes of blocking pipeline construction.

it’s still being done.

“The pipeline is running through the Adorers of the Blood of Christ’s property against their wishes that it not be there and against their religious beliefs,” says Dwight Yoder, attorney for the nuns who have been fighting the pipeline for several years. “We did file an initial reaction to try and stop that from happening under the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) and the courts said that because the Adorers had not requested the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) to basically raise their religious objections during that administrative process that they could not later try and stop the pipeline from going in through a court or legal action.”

Still, Yoder says the courts did not address the question of whether the Adorers could receive damages from Transco for violating their religious liberties.

“The Adorers decided that they would pursue a claim for damages against Transco and they filed a new lawsuit in October 2020,” says Yoder. “That lawsuit is also under the Religious Freedom Restoration Act and it basically says that because Transco went in and forced the sisters to use their land in violation of their religious beliefs to protect the earth and care for God’s creation, that Transco violated the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, and that those violations should be compensated with damages after a full jury trial.”

Transco, a subsidiary of Williams Companies, has asked the courts to dismiss the case. Oral arguments on that motion took place in January. Yoder is still waiting for a decision.

Despite the ongoing legal fight from the nuns, news outlets have moved on. So have a lot of the protestors.

Gordon Tomb, senior fellow for the Harrisburg-based Commonwealth Foundation, has an idea on why the sound of protestors has been replaced by crickets — in the case of this cornfield, literally.

“People attracted to the limelight of a cause may withdraw from the fray when a decision goes against them and media attention dissipates,” says Tomb, whom is also a senior adviser for the CO2 Coalition and primary editor of the book “Inconvenient Facts: The Science That Al Gore Does Not Want You To Know.” “However, I believe that those most committed to opposing energy development — or whatever — remain active in the background as they look for new opportunities to advance their political agenda.”

As a result, Tomb says developers of any new energy project, “had better be prepared to justify their proposal and address objections irrespective of how calm the landscape may look.”

As a result, Tomb says developers of any new energy project, “had better be prepared to justify their proposal and address objections irrespective of how calm the landscape may look.”

One effort anti-fossil-fuel activists are pursuing is a state constitutional amendment to give more power to local Pennsylvania communities to override state and federal authority to pre-empt local regulations on energy projects.

“As it is now, local communities cannot legally set standards to protect themselves and the environment in which they live beyond what the state says is okay,” says Malinda Clatterbuck, one of the most active anti-pipeline protesters and a co-founder of Lancaster Against Pipelines. “So, in other words, it is illegal for them to pass laws at the local level that would say ‘we as a community choose to live sustainably where we are not going to have fossil fuels in our community.’”

Clatterbuck, now serving as Pennsylvania Community Rights Network at Community Environmental Legal Defense Fund (CELDF), was arrested during the pipeline protests and performed 50 hours of community service in a deal to avoid prosecution. She says people of faith believe they have a responsibility to one another and to do as little damage to the earth and to each other as possible.

“There are no damages,” retorts Shepstone. “They can plant corn, hold services, or do whatever they want over the pipeline except to build structures on top of it and they’ve been compensated for that imposition.”

In late 2020, Transco paid a total of $700,000 to nine counties to resolve complaints of minor construction violations.

Shepstone says cases like the Atlantic Sunrise pipeline show opponents largely fall into two groups: Those motivated by ideology like the nuns, and a larger ‘Not In My Backyard!’ (NIMBY) segment of the community impacted by pipeline construction.

“It is all about ideology for them and the NIMBYs, both of whom receive encouragement and often financial support from rich foundations and tax-exempt ‘charities’ that are actually grass-roots lobbying entities for special interests in renewables,” says Shepstone.

Williams Companies did not respond to repeated requests for comment. Local residents contacted by Delaware Valley Journal were reluctant to discuss the issue.

“I do not think most residents care that much one way or another,” says Shepstone. “They are often simply disinclined to get involved with controversy and prefer to say nothing.”

Shepstone adds that few people want to challenge nuns.

“I’m a Catholic, but this is a radical leftist Catholic group,” says Shepstone. “To me, it is a group that is more worried about the world than the salvation of souls, and the large outdoor service area was a gimmick to try to stop this pipeline while they operate and heat facilities with natural gas.”