The Korean film “Parasite” has received such acclaim that showings in the cineplex in Washington where I first tried to see it were sold out. I had to go another night.

It was definitely worth the wait. Alternating between dark comedy and bloody tragedy, “Parasite” is a brilliant social satire on life in Korea that goes far beyond anything I had seen or knew. The plot is tightly constructed and acted by a sparkling cast portraying Koreans in a range of social strata, moods and settings.

The story line might be called an upstairs-downstairs view of the upper crust of Korean society and a downtrodden lower class. In this case, the bottom level, literally, is a secret tunnel complex way down below. As the film slowly, shockingly reveals, it harbors the manic husband of the dutiful woman responsible for managing the household of the wealthy couple and spoiled little boy who inhabit their high-walled, gated mansion.

Foreigners rarely penetrate the inner lives of Korea’s super-rich. In my reporting on Korean conglomerates and their founders and privileged progeny, I have never been invited into their homes with one notable exception years ago when I was working on a book about Chung Ju-yung, the late founder of the Hyundai empire. Having heard that he ordered his sons over to share his spartan breakfast every day, I asked an assistant if I could see this ritual for myself. Early one morning I got to watch from the vantage of a spacious kitchen overlooking the small table around which father and sons silently clustered.

I did get a sense of the divisions in Korean life as I looked on with several of their wives, who did not partake of the kimchi, fruit and tea on offer, but I would not have dreamed of a labyrinth of secret passageways hidden below. Nor would I have felt the intrigues, rivalries and resentments in their lives. With all the money in the hands of corporate chieftains, however, it’s not hard to imagine their defenses against the bitterness of a highly competitive society. The rich were, and undoubtedly still are, getting richer while mere commoners suffer from harsh discipline, low wages, unemployment and underemployment.

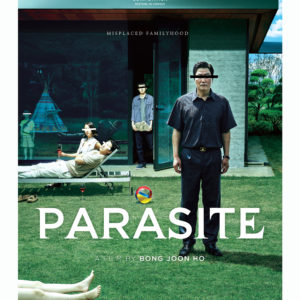

It’s no wonder that the director of “Parasite,” Bong Joon-ho, was just nominated by the Broadcast Film Critics Association in the United States and Canada for best director and, with Han Jin-won, for best screenplay. The film got a raft of other nominations — best picture, best foreign-language film, best acting ensemble, best production design and best editing. “Parasite” has already made Bong the first Korean director to win the coveted Palme d’Or at the Cannes film festival, and should be in the running for best foreign film at the Oscars to be bestowed in February by the American Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

This glittering list of accolades was not, however, on my mind as I watched the plot unfold in imaginative, innovative sequence and wondered what this spectacle said about class differences in Korea. The gulf between them comes to life not only in the device of the hidden tunnels but also in the dialogue, in the manners of rich and poor, in the condescension of the charming lady of the house and her superficially nice husband, in the frustrations of the tight-knit family of interlopers that nearly, hysterically, takes over their estate and their lives.

What is Bong, who has written and directed six other films, telling us? He eschews preaching, but the message comes through with stunning clarity in a story that provides one spellbinding surprise after another. One might ask if he’s more than a little unfair in this brutal portrayal of rich versus poor. Fair enough, but “Parasite” is gripping as both a terrific story and a commentary on modern life not only in Korea but in just about every society on earth, including my own.