Certain gifts are given to us year in and year out. They are the gifts that keep on giving and they come, to my mind, from people I call “The Overcomers.”

This Christmas week A.A. Gill, one of Britain’s most extraordinary newspaper columnists, died at the age of 62. Gill was nominally a food critic. He used that position as a launchpad for some of the most entertaining and acerbic writing anywhere.

His column in Britain’s The Sunday Times was a weekly joy. But Gill didn’t get there easily. First, he nearly died of alcoholism at the age of 30. He wrote a book about it.

Gill straightened out his drinking, but he never straightened out his awful spelling and severe dyslexia. He overcame them largely by phoning in his columns.

Gabriel Garcia Marquez, one of the greatest literary talents to come out of South America, struggled with terrible spelling that he detailed in his extraordinary autobiography, “Living to Tell the Tale.” But it didn’t stop him from authoring masterpieces like “One Hundred Years of Solitude” and “Love in the Time of Cholera.”

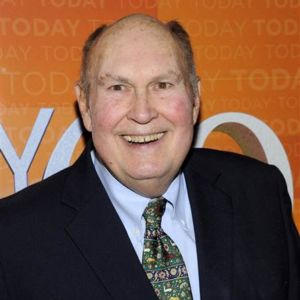

Willard Scott, who had a successful career in radio in the Washington market before making it as a personality and weatherman on NBC’s “Today” show, suffered acute stage fright. He testified before Congress so that his experience would help others.

But in my random selection of overcomers, the biggest is Laura Hillenbrand, the author of two nonfiction bestsellers, “Seabiscuit: An American Legend” and “Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience and Redemption.” Both were massive works of research and narrative writing.

The back story, though, is one of suffering, terrible unrelenting suffering. Hillenbrand is afflicted with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME), also known as Chronic Fatigue Syndrome.

This is a disease that knows no mercy; a life-sentence disease without a cure and no proven therapy. It punishes sufferers for any effort, even mild exercise, condemning them to bed, often for days. The symptoms are extreme fatigue, migraine headache, aching joints, hyper-sensitivity to light and sound, and dysphasia. Some patients are bedridden for years.

Hillenbrand missed her own wedding because she was unable to walk downstairs or to look down. Yet, this overcomer researched and wrote two extraordinary books. Just as important, in a seminal July 7, 2003, essay in The New Yorker, she told her own story, comforting fellow sufferers and prompting the medical world to take ME more seriously.

My favorite overcomer was a waiter at the National Press Club in Washington, known simply as Mr. Blue. He was a man of such innate dignity that everyone called him “Mister,” and no one seemed to know his first name.

Mr. Blue had had a hard life as an African- American with no education. In fact, he was illiterate, and I was one of the few to find out.

At the club in the 1970s, when I knew Blue, the waiters carried loose, paper checks on which members wrote their orders and club numbers. Blue survived by feats of memory, remembering who had written out which check by keeping them in order. One day, his system failed: He dropped his checks. Mr. Blue was distraught to tears.

Shame is a powerful censor and, like most censorship, it neither helps the sufferer, nor does it do anything for the body politic. No one wants to be famous for their inadequacies or their sickness. But going public comforts and is a gift. It is the gift, so important in the holidays, of saying: You are not alone.

In that spirit, I have to go public with this: I am, for a broadcaster, a bad sight-reader. I have mild dyslexia, and I’ve been humiliated by my terrible spelling all of my long life in journalism. Happy holidays!