MANILA ― The Philippines president, Rodrigo Duterte, has a lot in common with President Donald Trump. He upsets people with tough talk, flays his foes with harsh words, and is accused of numerous offenses against women, against the media, also against the United States.

And he’s been courting the leader of a country with which his predecessors in Malacanang, the historic Spanish-built presidential mansion and office complex, have not always been on good terms.

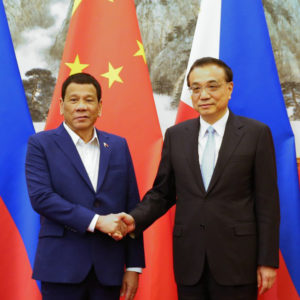

The object of Duterte’s affections since his election three years ago has been China’s President Xi Jinping, whom he has visited in China and then hosted at Malacanang last November. Both of them called that meeting a “milestone” in relations between the two countries but have yet to get down to serious business about China’s claim to the entire South China Sea, including small islands occupied by Philippine forces.

Now, however, it’s getting to be crunch time. The Philippines charges China with having sent military vessels around small southern Philippine islands, and Philippine leaders, but so far not Duterte, are saying enough is enough, we’re not going to stand for that any more. Defense Secretary Delfin Lorenzana charges Chinese vessels have been cruising around the southernmost islands without letting anyone know what they were doing, much less asking permission.

The Philippines foreign secretary, Teodoro Locsin Jr., got into the act with a fiery declaration at the Philippine senate calling for a “diplomatic protest” and demanding his government declare, “They’re trespassing.” Otherwise, as one senator responded, “We’ll be deemed as accepting their incursions into our territory.”

The rhetoric got almost comical when Lorenzana warned that Chinese corporations might well be spying on Philippine bases from the vantage of gambling operations near the major headquarters here of the armed forces. The Chinese ambassador had a ready response, suggesting that some Filipino workers in China, most of them simple household servants, might be spying for the Philippines.

The headline-grabbing accusations, however, mask one reality that Philippine leaders really don’t want to recognize fully. That is that the Philippine armed forces are woefully ill-equipped to defy any significant foreign force, much less that of China, whose warships and planes have been enforcing Chinese claims to the entire South China Sea.

The AFP, that is, Armed Forces of the Philippines, consists of about 170,000 men and women who have more than enough to do fighting off dual insurrections by both Muslim terrorists and the communist-led New People’s Army. The Philippine air force consists of only a few helicopters and transport planes while the navy has several frigates and patrol boats cruising around the country’s 8,000 or so islands.

Under the circumstances, Duterte’s position has been that it’s a good idea to get along with the Chinese while not relying on the Americans. He was outraged that President Barack Obama should have treated him coldly during an international gathering, after which he seemed on the verge of simply breaking the historic alliance with the United States, which survived the withdrawal of U.S. troops from Clark Air Base and Subic Bay, (at the time) the largest U.S. air and naval bases outside the United States, in 1991 and 1992.

Duterte gets along much better with Trump, in whom he senses a kindred spirit, but he’s still dubious about the U.S. commitment to defend the Philippines against the Chinese in a showdown. It was one thing for the United States to drive the Japanese out of the Philippines in 1945 after the Japanese had driven out U.S. forces soon after bombing Pearl Harbor in December 1941, but his sense is that U.S. forces these days are not going to come to the rescue.

Against that background, Duterte is in China this week for yet another summit with Xi. He has promised, this time, seriously to raise the whole issue of the Chinese infringing on Philippine sovereignty by getting too close to Philippine islands and declaring their supremacy over the entire South China Sea.

Duterte knows perfectly well that the armed forces of the Philippines cannot do a thing about the Chinese on their own, and he’s sure the United States would be in no mood to go to war in the South China Sea even though U.S. warships have sailed through those waters in defiance of Chinese warnings. In practical terms, probably the best Duterte can do is suggest to Xi the notion of a treaty involving other countries with a stake in the sea, notably Vietnam and Malaysia and the sultanate of Brunei.

But will Xi go for such an idea? He does not seem eager for war, but he’s also showing no signs of yielding on China’s claims. It’s a standoff that appears likely to simmer on while Philippine politicians wage a war of words that the Chinese can safely ignore in the certainty that the Philippines cannot back up words with deeds.