Editor’s Note: For an alternative viewpoint, please see: Counterpoint: Stop It With the Sexist ‘Likability’ Test.

Several prominent women are seeking the Democratic Party’s nomination for president. Some worry these female candidates will face an unfair “likability” standard, which they see as a new twist on plain old sexism.

Yet all candidates — men and women alike — have to worry about coming across as likable. There’s nothing sexist about it.

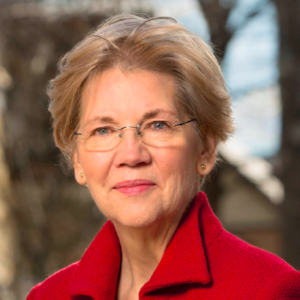

The like-ability issue is top-of-mind since many blame Hillary Clinton’s loss on a like-ability deficit, and worry that history might repeat itself next year. For example, Politico posed this question after Senator Elizabeth Warren announced her candidacy: “How does Warren avoid a Clinton redux — written off as too unlikable before her campaign gets off the ground?”

Women’s Media Center worried about the treatment of the Democratic women seeking the nomination: “Even before the media gave these women’s political visions a chance, it has largely narrowed in on evaluating whether these women possess a single quality — one that they seem to care about only when it comes to female candidates: their likability.”

But it isn’t just female candidates who are judged on their ability to appeal to and connect with voters. This has been a central issue in all modern elections. In 2008, a Newsweek article titled “The Likability Factor” detailed how future president Barack Obama clobbered Senator John McCain, not on the substance of the presidential debate but on being more likable — which has been critical since the advent of television:

In 1984, Ronald Reagan struck voters as about 20 percent more likable than Walter Mondale. George H.W. Bush defeated Michael Dukakis largely because he “triumphed in the congeniality competition” — and later lost to Bill Clinton largely because he didn’t. After the Oct. 17, 2000, debate, voters rated George W. Bush the more likable candidate, 60 percent to 30 percent; four years later, Dubya whipped John Kerry 52 percent to 41 percent in the same department. In other words, the candidate who won the debates may not have won the subsequent election — but the candidate who came off as most congenial almost always did.

Likability isn’t a sexist criteria. It’s a criteria that people consider in most situations. We want political leaders — and media personalities, teachers, salespeople and celebrities — who we can relate to and enjoy seeing as they become part of the backdrop to our lives. There is nothing new or nefarious about this.

The media’s newfound concern about likability seems driven by their desire to see whoever wins the Democratic nomination to resoundingly beat President Trump. If they can’t beat Trump on policy and results, they’ll beat him on likability.

The media will work overtime to make these Democratic women as likable as possible. From women’s magazines to daytime television to news reporters — the media will routinely offer soft coverage that makes them seem as relatable, aspirational and likable as possible. You’ll see pictures of these women in “authentic-looking” family settings, caring for the sick, holding babies, laughing with happy crowds at wholesome gatherings, and lots of really fun, cool activities to try to meld their images with what we associate with people who are kind, compassionate and fun-loving.

For those with likability issues, the media will launch into damage control mode. They will attempt to blunt criticism that Warren is too cold and calculating, or that Senator Amy Klobuchar is phony and cruel to staff. If that doesn’t work, the backup plan is to de-legitimize the concept of likability for female Democrats as sexism.

With President Trump they do the opposite. Not only will they make him look as boorish and off-putting as possible, but they will push the idea that these are legitimate reasons to oppose him. When his approval ratings are low they’ll say he has likability issues and won’t win re-election. When his approval ratings improve, they won’t report it or will dismiss it as for all the wrong reasons. They’ll suggest that if you do like him or will vote for him, there’s something wrong with you. You’re unlikable.

Many voters likely will see through this media manipulation. Of course, voters will prioritize evaluating the agendas offered by the candidates, to determine who has a better plan for creating a stronger country with better opportunity for all. But they will also consider candidates’ personal attributes, including who they like more.

There’s nothing wrong — or sexist — about that.