Editor’s Note: For another viewpoint, see Counterpoint: Yes, Trump Should Pardon Edward Snowden

Presidents were given the pardon power for two principal reasons: One, in times of crisis, a timely pardon might be in the country’s national interest and two, when the letter of the law creates an inequity in its application.

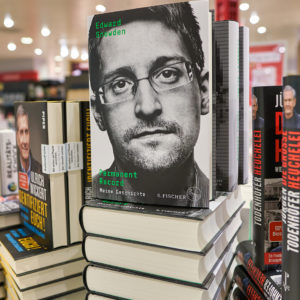

Neither situation applies to Edward Snowden. To the contrary, his decision to steal 1.5 million highly classified documents from U.S. intelligence and make them available to journalists and, when published, America’s adversaries, is deserving of an extended stay in federal prison.

Snowden’s supporters claim that by exposing a National Security Administration program that collected a mass of telephone meta-data (time, duration and end points of calls but not their substance), he was engaged in an act of civil disobedience.

The American public needed to know what was going on behind NSA closed doors in the name of supposedly fighting terrorism.

But was it illegal what NSA was doing? Not according to two different administrations, one Republican (Bush), one Democrat (Obama). Not according to the federal courts either.

The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court on multiple occasions had approved the program and the Supreme Court had validated collection of such data as information that phone companies already had on hand as part of doing business and, hence, couldn’t be thought of as private.

Whatever the program’s substantive merits — and reasonable people can differ on that — it’s important to remember that, after 9/11, the complaint was that the government had not been forward leaning enough when it came to collecting intelligence and has missed leads because it was not “connecting the dots.”

The NSA program was an effort to collect the dots so they could be connected. If you knew a terrorist’s cell number, then knowing what other numbers were in touch with him might be a critical piece of intelligence.

Moreover, as a House intelligence committee report on the damage done by Snowden noted, “the vast majority of the documents he stole have nothing to do with programs impacting individual privacy interests — they instead pertain to military, defense and intelligence programs of great interest to America’s adversaries.”

Indeed, “leaks” from Snowden’s stash have led to terrorist groups changing methods of communication to enhance security, and the compromise of the covert ways the CIA and NSA are able to penetrate computer systems from afar and even without those systems being tied to the internet.

Indeed, also given away was the fact that U.S. intelligence was able to listen in on the Russian president’s calls and had penetrated key Chinese servers in Beijing. At the end of the day, Snowden’s disclosures have closed off successful collection operations that cost millions to develop against critical targets having nothing to do with American citizens.

Putting Snowden on a pedestal is hard to take given his own track record of deception.

He lied as to why he washed out of the Army; he lied about the level of work he did at CIA in order to get another job; he doctored his resume and his performance evaluations and — according to the House report — he stole answers to an employment test in order to obtain his position associated with the NSA.

And, of course, he lied to his supervisor about taking a few days off for medical treatment when in fact he was hightailing it to Hong Kong and eventually making his way to Moscow.

The reason to bring up these character issues — and putting aside for the moment the massive amount of material he took with him unrelated to civil liberties — is that Snowden had other avenues through which he could have raised his concerns about the NSA collection program.

Each agency has an inspector general’s office whose responsibility it is to look at charges of illegality or impropriety; and each agency has processes intended to protect whistleblowers.

Finally, if Snowden believed he hadn’t received satisfaction from that office, or that he couldn’t use them for whatever reason, he could have gone to either the House or Senate intelligence committee.

As a former staff director of the Senate committee, I can attest that it was not unusual to receive complaints from Intelligence Community employees on this or that issue, which we would then follow up on.

Snowden’s actions are not that of true civil disobedience where an individual breaks a law in protest but, out of respect for the broader rule of law, accepts jail time.

A pardon for someone who clearly thinks he is above the law is neither necessary nor appropriate.