As a rule of thumb, most economists would agree that when a consumer is truly satisfied with the price and quality of a good or service, the seller shouldn’t need to have the federal government pass laws making the transaction mandatory.

And when those laws are abolished, the seller shouldn’t need to commit a felony in order to keep pretending they hadn’t been.

And yet the nation’s government employee unions continue to insist — despite mountains of evidence to the contrary — the millions of people they claim to represent couldn’t be happier.

For decades, you may remember, public employees in states that lacked right-to-work protections were required to either join a union and pay dues, or surrender their membership rights but still pay a so-called “agency fee” instead.

All that changed in 2018, however, when the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed in Janus v. AFSCME that compulsory union membership, dues and fees in the public workplace were a violation of the employees’ First Amendment rights.

But rather than simply getting out of the way and allowing millions of workers to defect — or commit to earning their loyalty by actually providing better service for lower dues — the unions adopted a policy of contesting every single opt-out by any means necessary. Legal or otherwise.

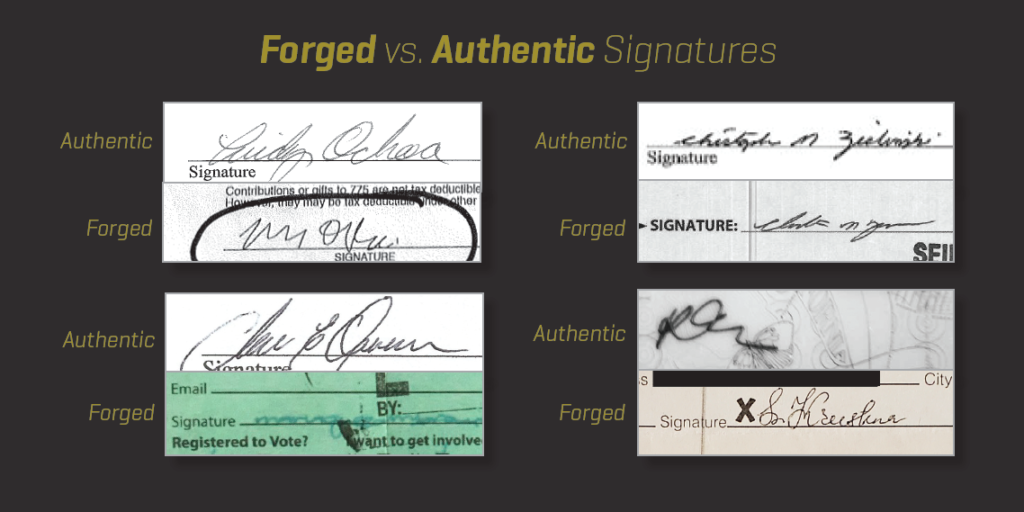

In a shocking number of cases, in fact, unions have simply forged a worker’s signature on their membership card and continued to charge dues illegally.

Among the most egregious examples:

— Yates v. WFSE. When Sharrie Yates, a medical assistant with Washington state’s Healthcare Authority since 2004, attempted to opt out of the Washington Federation of State Employees in October 2018, the union denied her request citing an electronic renewal form she allegedly submitted the previous June. Yates can prove she never submitted an electronic signature, but despite numerous attempts to contact the union, it continues to deduct dues from her paychecks.

— Cash Schiewe v. SEIU 503. The plaintiff, who works for Oregon’s Department of Consumer and Business Services, asked to opt out of Service Employees International Union (SEIU) Local 503 after Janus, only to be told by the union the court ruling meant she now had to join the union. When she later learned the truth, she confronted the union only to be told she had signed an electronic membership form in the meantime. But the form SEIU 503 produced does not contain her signature — and does not contain accurate metadata that would establish a valid electronic signature.

— Wright v. SEIU 503. The plaintiff is a public employee who works for the Oregon Health Authority. SEIU 503 claims she signed an authorization for dues deductions in October 2017 on an iPad — but the employee disagrees, having no recollection of signing up for union membership. When asked for supporting evidence, SEIU 503 could not produce data to confirm the signature, but nonetheless continued to enforce it to take union dues.

— Semerjyan v. SEIU 2015: The plaintiff, a California homecare provider, has had dues deducted from her paycheck since 2003. At first she believed union membership was mandatory, but in the wake of Janus she sent an opt-out letter in October 2019. The union responded, saying she signed a membership card and couldn’t leave until March. She demanded to see the membership card on file and, when it arrived, she quickly recognized it had been forged. SEIU 2015 denied the forgery, then compounded its lies by claiming her husband may have signed it for her.

There are more, but you get the idea.

From at least 1977 until 2018, America’s public-sector unions had a monopoly over the workplace that amounted to a license to steal. If it takes a little forgery to go right on stealing, it’s well worth the risk.