Getting soaked on Splash Mountain did not bring me joy.

But getting soaked year after year for the last 20 years brought our daughter joy and her joy brought us joy.

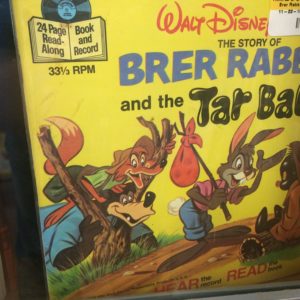

Most of the joy was from the soaking, but some of it was from rooting for Brer Rabbit as he recklessly pursued happiness without getting grabbed and eaten by Brer Fox and Brer Bear. Near the end of the ride, right before the big soaking, Brer Fox tells Brer Rabbit that he will either “hang ya” or “roast ya” or “skin ya.”

Brer Rabbit replies that any of those would be fine, but please, please don’t do what he most dreads — “being thrown in the briar patch.”

Brer Fox does not know that Brer Rabbit has what economist F.A. Hayek calls “local knowledge” of the ins and outs of the briar patch. So Brer Fox is tricked, Brer Rabbit escapes, and we get soaked. Joy all around, except for Brer Fox, who is last seen with his tail in the teeth of a grinning Brer Gator.

In the original black slave folk tales, and in Disney’s version, Brer Rabbit is an upbeat trickster who always finds ways to outsmart his powerful enemies. Until now, that is — now it seems he cannot outsmart the Walt Disney Company that plans to respond to a recent online petition by evicting Brer Rabbit from his Splash Mountain home.

The petition claims that Disney’s “Song of the South” movie is racist, and that Splash Mountain should be re-themed “to remove all traces of this racist movie.”

The core of the movie is the animated story of Brer Rabbit, which is embedded in a live-action story of plantation life. The live-action part shows masters and slaves living together harmoniously, which some see as whitewashing the sins of slavery.

But the theme of Splash Mountain is based only on the animated part — only on the Brer Rabbit black slave folk tale. Brer Rabbit can be admired, and Splash Mountain enjoyed, without endorsing ante-bellum plantation life.

Walt Disney retold beloved meaningful folk tales, sometimes giving them a more hopeful ending. He often adapted European folk tales, but also wanted to include black slave folk tales.

The Brer Rabbit stories have been criticized for their dialect. But that misses the point. Just as with Mark Twain’s “Huckleberry Finn,” the soul of the stories is in what is said and done, not in the dialect of the dialogue and narration.

Some intellectuals have found the Brer Rabbit tales instructive — novelist Toni Morrison expands on a Brer Rabbit tale in her “Tar Baby” novel. Others disagree.

When Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Maria Tatar edited their “Annotated African American Folktales,” Tatar at first wanted to omit Brer Rabbit. But Gates, who is the director of a center for African-American research at Harvard, grew up listening to his father tell the tales of crafty resourceful Brer Rabbit. Gates wanted to pass those tales on to his granddaughter.

Like Brer Rabbit, Walt Disney was resourceful. When he was a young man, a badly written contract allowed a powerful enemy to take from him his first successful cartoon character: Oswald the Lucky Rabbit. So on the train trip back to Los Angeles, Walt shortened Oswald’s ears and lengthened his tail, creating a mouse called “Mickey.”

On the last page of his excellent biography of Walt Disney, Michael Barrier writes that the young Walt was a “human Brer Rabbit, constantly wriggling out of the snares set for him.”

If so, then by evicting Brer Rabbit from Splash Mountain, Walt Disney the company, is evicting the spirit of Walt Disney the man.