Little League Baseball’s civil war was fought in the South in 1955 — almost a hundred years after the Civil War — after White teams refused to take the field against Black teams in the aftermath of the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education the previous year that ruled that segregation in public schools was unconstitutional.

Sen. Strom Thurmond of South Carolina called for Southern states to “resist integration by any lawful means,” regardless of whether it applied to schools, theaters, swimming pools, or Little League Baseball.

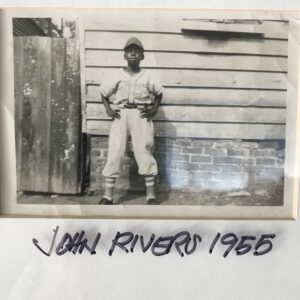

When a Black team, the Cannon Street YMCA all-stars of Charleston, S.C., registered for a previously segregated district tournament, the White teams withdrew in protest. The Cannon Street team won by forfeit and advanced to the state tournament.

Danny Jones, the state tournament director, asked Little League Baseball for the tournament to be segregated. Peter McGovern, the organization’s president, refused. This, he said, would violate the organization’s rules prohibiting racial discrimination.

An indignant Jones resigned from Little League Baseball and created his own segregated baseball organization. Hundreds of Southern teams left Little League Baseball to join the rebellious organization now known as Dixie Youth Baseball.

“Dixie Youth Baseball was founded on the tears of the Cannon Street players,” said Gus Holt, who revived the team’s story in the 1990s.

Sports Illustrated later called this “Little League’s Civil War.” It became the greatest crisis in the history of Little League Baseball.

The 75th Little League World Series began in Williamsport, Pa., on Aug. 17 and ends with the championship game on Aug. 28.

Little League Baseball prohibited racial discrimination when it was founded in 1939. In 1955, Little League’s rule, however, directly conflicted with Southern laws that prohibited integration.

The Cannon Street team won the South Carolina tournament by forfeit and advanced to the regional tournament in Rome, Ga. If the team won that tournament, it would have become the first all-Black team to play in the Little League World Series in Williamsport.

The boys’ dreams of playing in Williamsport ended in Rome.

George “Buck” Ransom, the director of the regional tournament, declared the Cannon Street team ineligible because the organization’s rules said a team could only advance by winning on the field, and it had won by forfeit.

McGovern, who had supported the Cannon Street team until then, upheld the decision for reasons that perhaps had less to do with complying with rules than fear of racial violence.

McGovern expressed concern for the safety of the 11- and 12-year-olds on the Cannon Street team if they went to rural Georgia. “We felt they might be subjected to every hate and prejudice in Rome,” he said in a wire service story.

His fears were real.

The Brown decision revived the Ku Klux Klan throughout the South.

Holt said he thought there was a real threat to the boys’ lives. Someone told McGovern, Holt said, “If you send those n—–s down there, there will be blood on your hands.” There is no doubt that such a conversation took place, Holt said.

There is no record of such a conversation. There is no record of an active KKK in Rome in the summer of 1955, but the Klan had a big presence in Atlanta and elsewhere in Georgia. There is no doubt that the potential existed for racial violence. There is no doubt that some of those who resisted segregation met with harm.

The Brown decision confronted Jim Crowism in the South, and Southerners took up arms to defend their way of life. In the next decade, violence would explode in the South, and the dead would include children: Emmitt Till in Mississippi in August 1955 and four girls who died in a Klan bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Ala., in September 1963.