Every field of endeavor gets stuck in a rut and it takes a pioneer, a rebel, to blast it loose. In journalism and literature, Tom Wolfe, who has died, age 88, did that, starting in the 1960s.

His incendiary device was the “New Journalism.” It used the techniques of the novel in observation and quoted speech for news and feature writing. Wolfe was its exemplar with unequaled verbal pyrotechnics.

In the summer of 1963, I had the luck to work in the same room as Wolfe at The Herald Tribune in New York City. He was in the initial stage of shaking up journalism.

That golden summer, somehow, some of the greats of American journalism found themselves at “The Trib,” a newspaper that had had a history of shaking up journalism and was doing it again.

By 1963 the newspaper was suffering from years of poor business decisions, which had reduced it to near bankruptcy. It had been bought by the oil billionaire Jock Whitney to provide a conservative voice to counter the liberal New York Times.

What Whitney got was a cornucopia of newspaper talent.

Probably never before or since have so many gifted wordsmiths been assembled in the same place: a championship season of talent that was to affect journalism for a generation.

Altogether Murray “Buddy” Weiss, who was the managing editor, and I calculated, long after the paper had failed in 1966, that 67 people who worked at the paper went on to major journalistic success. The names included Eugenia Sheppard, Jimmy Breslin, Red Smith and David Laventhol, who later created the Style section of The Washington Post and fired another newspaper revolution.

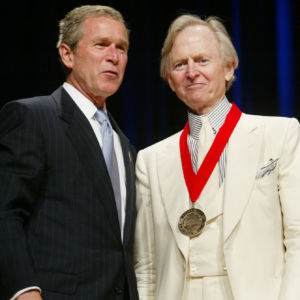

And sitting there, in the middle of one of long tables where the reporters sat, was one Tom Wolfe, already wearing the white suit that was his trademark all the long years of his success. The tailoring got better over time, but the color remained.

Wolfe got to New York via a Ph.D. in philosophy from Yale and stints at The Springfield Union and The Washington Post. At both papers editors knew he had talent, but sort of ignored it.

Fortune helped Wolfe along when The Trib was closed by a strike in 1962 and he contracted with Esquire magazine to travel to San Francisco and look at psychedelic paint jobs on cars.

Wolfe discovered the counterculture and Esquire discovered what became known as the New Journalism — a term that he didn’t really like. When he had difficulty putting his discoveries into traditional journalistic form, his editors told him to send them a memo and they would write it for him.

He did and they published the long, long memo, 49 pages, in full: “The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby.” It was unique in reporting history. It also introduced Wolfe into the world of the counterculture that he, along with Hunter S. Thompson and others, was to chronicle.

But unlike Thompson, Wolfe never joined the counterculture. He reported on it and gave it a language of its own, drawn from how people in the culture spoke, but remained a courtly Virginia gentleman.

One of the many gifted people at The Trib at the time was Clay Felker, editor of the newspaper’s magazine, which survives today as New York Magazine.

They were made for each other and Wolfe, the reporter and wordsmith, was on his way with Felker guiding and cheering. A collection of Wolfe’s pieces came out in 1965 and the New Journalism became the rage, especially in magazines. Other names like Gail Sheehy, Gay Talese and Joan Didion were soon in the flux.

But Wolfe was the supreme writer and reporter. His masterpiece on the space program and the Mercury 7 astronauts, “The Right Stuff,” his blockbuster novel, “The Bonfire of the Vanities” and another novel, “A Man in Full” were all built on meticulous reporting.

Wolfe “pushed out the envelope” — one of the many phrases he has left us with — in reporting, writing and creative punctuation. A few other Wolfe-isms: “me generation,” “radical chic” and “master of the universe.”