For a long time, there was nothing. After Sen. John McCain quietly dropped his advocacy of cap and trade, the Republican position on climate change could almost be summed up with one word: No.

Republicans were a “no” on Waxman-Markey, which would have established a national cap-and-trade program. They were a “no” on the Obama administration’s Clean Power Plan, a “no” on the Paris Agreement on climate, and a big fat “hell no” on the Green New Deal.

There’s nothing wrong with saying “no” to bad policies. Saying “no” is, in fact, a proud Republican tradition. Over time, however, a sense grew that on climate change, it wasn’t going to be enough to simply say “no.” And so a number of Republicans began advancing a positive agenda on climate. What’s more, instead of simply developing “diet” versions of Democratic proposals, Republicans have increasingly shown creativity on the issue, putting forward proposals to deal with the risks and costs of warming that are rooted in conservative principles.

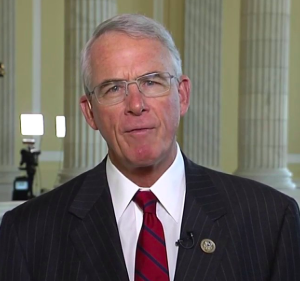

Consider the latest proposal, filed last month by Rep. Francis Rooney of Florida. The bill would create a carbon tax of $30 a ton. Imports from heavy emissions-producing countries like China would be taxed, while U.S. exports would be exempt to make sure our international competitiveness is not harmed. The bill would also freeze attempts by the Environmental Protection Agency to impose its own restrictions on greenhouse gases until 2030.

Rooney’s approach is in keeping with that endorsed by most economists, who see a price on carbon emissions as a better way to reduce greenhouse gases than complex and unwieldy regulations. Instead of having the federal government try to micromanage the energy sector, Rooney’s bill would encourage individuals and businesses to decide for themselves how best to reduce their carbon footprint.

What’s most new and interesting about the Rooney bill is the way the revenues are used. The bill provides that the bulk of the money raised will go to support cuts to payroll taxes. Additional money would be used to fund state block grants, weatherization and energy research and development.

This “tax swap” would help to resolve one of the perversities of the current tax system. When you tax something, you tend to get less of it. That’s the idea behind taxes on cigarettes, for example. Yet America currently imposes heavy taxes on things like jobs and savings that we ought to want more of. Swapping taxes on things we want to encourage for things we want less of should be common sense.

It also shows that taking meaningful action on climate change need not hurt the economy or low-income workers. In fact, by lowering the cost of hiring workers, the bill could boost job growth. This is in line with research from Columbia University, which shows that a carbon tax could mean economic growth if it is used to help cut more economically damaging taxes.

Beyond the specifics, the bill shows a growing appetite among conservatives to be proactive on the climate issue. And it shows that conservatives are capable of providing serious, detailed plans on this issue. Many Democrats have been quick to embrace the slogan of the Green New Deal, but figuring out what that actually means has proven challenging. Rather than a costly and bureaucratic plan, conservatives should continue to put forward their own vision of how to deal with climate change while growing the economy and unleashing innovation.