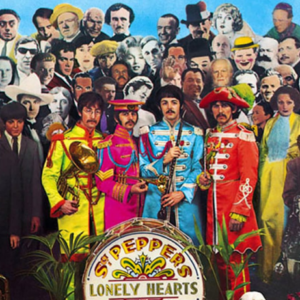

Last month marked the 50th anniversary of the release of the Beatles’ “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band,” the record album that Rolling Stone has rated as the No. 1 album of all time.

While the artistic and creative merits of the Beatles and the “Sgt. Pepper’s” album are widely recognized, virtually no one has acknowledged that it was capitalism that made it possible for four young lads from working-class Liverpool to revolutionize popular music.

The creative merits of “Sgt. Pepper’s” are beyond debate. Coupling the Beatles with producer George Martin and engineer Geoff Emerick, two technical professionals equally enthusiastic about pushing the boundaries of contemporary music, ignited an artistic revolution that affected generations and changed the course of popular music.

They pushed beyond the boundaries of known technology to change tempos, create new sounds, shift keys within songs, and blend acoustic, electric and orchestral arrangements in ways no one had ever contemplated before. For the first time, the studio became an integral part of the creative process.

The combination resulted in “the most important rock & roll album ever made,” according to Rolling Stone, and the first to win a Grammy for album of the year. More than 32 million copies reportedly had been sold prior to this year, with the new 50th anniversary “remix” generating many more additional sales.

But this is not the entire story. Creative genius is not a guarantee of success. Rock music was still relatively new in 1967, developing in an uncertain market, and considered by many a cultural backwater. Something else was necessary to enable the Beatles to upend artistic and musical conventions.

That something was capitalism, which allowed the Beatles and their investors to monetize their earlier performances and experimentation on a global scale, creating the conditions necessary for the “Sgt. Pepper’s” album to be produced.

The Beatles walked into EMI’s Abbey Road recording studios on November 26, 1966, with an effective blank check to create, economically free from the need to tour. They finished the album on April 21, 1967 — nearly five months later — having spent an unprecedented 400 hours in the recording studio.

All told, Emerick, the recording engineer, estimates that 700 hours were spent on the album, more than 30 times the amount spent on their first album — and at more than 60 times the cost.

Yet, the studios were not breathing down their necks to shorten their recording time to push another record out the door.

Why? Because the Beatles and their recording labels could afford it.

At the time, the Beatles were the world’s biggest attraction, making their record labels — Capitol Records in the United States and Parlophone Records in the U.K. — very wealthy. John, Paul, George and Ringo easily could have retired from music and never “worked” another hour.

The studio time wasn’t a gift from the record labels or EMI studios. The Beatles had established an extraordinary work ethic and dedication to their music. They had created a worldwide platform of fans. Industry executives could gamble that their time and creativity in the studio would pay off in additional worldwide sales. The investment paid off. Spectacularly.

Critics consistently and unrelentingly knock capitalism, arguing that it produces inequality and concentrates wealth. But the wealth it creates also produces freedom and opportunity, benefits that are not discussed nearly enough.

The creative and commercial success of the Beatles and “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” is an important example of how the capitalist economic system creates new wealth, putting it in the hands of innovators who can change the world for the better.

Without capitalism, the Beatles might not have gone much further than playing club dates in Liverpool and Hamburg, Germany. Capitalism brought them — and “Sgt. Pepper” — to the world.