In an old joke, a repertory company prepares to stage “Hamlet” when the lead actor dies just before the first performance. The company frantically appeals to the packed audience for someone who knows Hamlet’s part. A volunteer steps forward, an egotistical fourth-rate actor, and it is immediately clear he is terrible. So bad that when he reaches the famous “to be or not to be” soliloquy, the audience begins booing and throwing things at him. Finally, he breaks character, walks toward the audience, and amidst a volley of overripe turnips, says, “Don’t blame me. I didn’t write this junk.”

This joke resonates these days in part because of a woman named Lorena German, chair of the National Council of English Teacher’s Committee Against Racism and Bias in the Teaching of English (whew!). German has been featured in The New York Times and is also co-founder of Disrupt Text. According to its website, Disrupt Text “is a crowdsourced, grassroots effort by teachers for teachers to challenge the traditional canon in order to create a more inclusive, representative, and equitable language arts curriculum.”

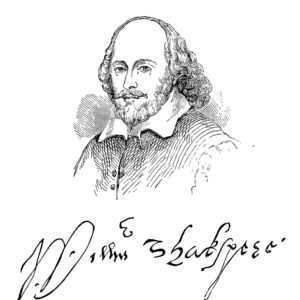

Shakespeare is a primary target of German. She has written, “We believe that Shakespeare, like any other playwright, no more and no less, has literary merit. He is not ‘universal’ in a way that other authors are not. He is not more ‘timeless’ than anyone else… overall, we continue to affirm that there is an over-saturation of Shakespeare in our schools and that many teachers continue to unnecessarily place him on a pedestal as a paragon of what all language should be… This is about an ingrained and internalized elevation of Shakespeare in a way that excludes other voices. This is about white supremacy and colonization… Considering the violence, misogyny, racism, and more that we encounter in Shakespearean texts, we offer up the notion that we can open our minds and classrooms to texts that celebrate the voices and lives of marginalized people, speak to the students in front of us, and reflect a better society. It is also imperative that we reflect and act to correct the messages educators and school systems send children about whose language is superior, whose stories are ‘universal’, and whose history should be carried into the future.”

A passage such as this makes you wonder whether German has ever actually read Shakespeare. No matter, she is obviously intent on inflicting such nonsense on future generations.

Shakespeare’s characters exhibit every human emotion: Strength, and frailty – Othello’s jealousy, Iago’s treachery, Portia’s wisdom, Hamlet’s spiritual indecision – and these are just a few of his major characters. Even in his drawing of minor characters, there is unmatched brilliance. Not universal? Not timeless? For centuries, the world’s greatest scholars have written volumes demonstrating the utter foolishness of these assertions.

And when German inevitably retreats to the political to justify her drivel, she is left unmoored. Maya Angelou famously imagined things that have eluded German, “When I physically and psychologically left that country, that condition, which is Stamps, Arkansas…I found myself and still find myself, whenever I like stepping back into Shakespeare…of course he was a Black woman. I understand that. Nobody else understands it, but I know that William Shakespeare was a Black woman.”

If it is class struggle where German finds fault with Shakespeare, it turns out two men with especial bona fides were devotees of The Bard. According to Karl Marx’s daughter, he read Shakespeare regularly and his family would walk back from their regular Sunday picnics on Hampstead Heath, dramatically reciting extracts from Shakespeare’s plays to each other.

Leon Trotsky once described Marx’s interest in Shakespeare. “In the tragedies of Shakespeare, which would be entirely unthinkable without the Reformation, the fate of the ancients and the passions of the medieval Christians are crowded out by individual human passions, such as love, jealousy, revengeful greediness, and spiritual dissension. But in every one of Shakespeare’s dramas, the individual passion is carried to such a high degree of tension that it outgrows the individual, becomes super-personal, and is transformed into a fate of a certain kind.”

In pre-Maoist China, and in the early days of the Communist Revolution, Shakespeare was popular. During the Cultural Revolution, his works were banned in China for a decade. Tellingly, after Mao’s death, the ban on Shakespeare was lifted – a significant event in the country’s cultural history.

Recently, NBC journalist Andrea Mitchell misidentified the source of the well-known phrase “sound and fury” as being from William Faulkner when it actually first came from one of Shakespeare’s greatest passages from Macbeth. This is something not everyone, but certainly someone with a degree in English literature from an Ivy League university (as Mitchell has) should know – another reminder of how deemphasizing Shakespeare demonstrates our willing flight from the Age of Enlightenment. Ultimately, this communal exodus will leave our society less wise and with less moral insight: coarsened, deadened souls with a poorer understanding of humanity and human nature. This will not bend society toward any sort of justice but away from it. Praise from The New York Times and their ilk are merely further proof these institutions have become all too eager to promote mediocrity and willing to praise the undeserving.

George Bernard Shaw, another great literary eminence currently out of favor, once said, “I pity the man who cannot enjoy Shakespeare … the imaginary scenes and people he has created become more real for us than our actual life.”