The Senate Committee on Rules and Administration will hold a hearing soon on S. 1, the ‘Corrupt Politicians Act.’

While much has been discussed about the effect the proposed legislation would have on the conduct of elections in the U.S., not so much has been discussed about the DISCLOSE Act, one of the more than 60 different pieces of legislation wrapped up in S. 1, and the effect the legislation would have on non-election-related political speech – that is, the kind of political speech that occurs when citizens band together to try to have an impact on the development or passage of legislation. So let’s be clear: The new donor disclosure requirements contained within this bill are so outrageous that if it were to be enacted into law, the result would be that we’d have a lot less non-election-related political speech.

Shutting down political speech is bad enough. What’s worse is that this bill’s sponsors know this will be one of the likely effects – and, for its most determined advocates, this seems to be a primary purpose of the legislation.

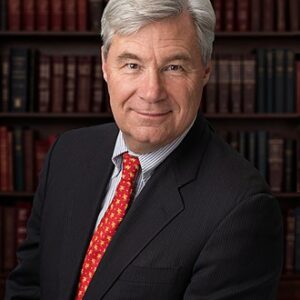

For instance, Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-R.I.), the principal Senate sponsor of the DISCLOSE Act, tipped his hand when he spoke just weeks ago to a Facebook live virtual townhall activist training session.

Whitehouse explained, “What the bill would do is require anybody who’s spending more than $10,000 … to declare that it’s them. … And what that means is two things: First, a lot of what is coming across now, behind fake names, you know, ‘Americans for Peace and Puppies and Prosperity,’ or some group that is a FedEx drop, that suddenly has to have real people behind it. And so they’ll have accountability for what they say. … And the second thing, my guess is that more than two-thirds of the big money just goes away. … And I’ll be prepared to take a small bet from anybody that two-thirds of it, of the unlimited spending, goes away as soon as it’s not unlimited anonymous spending.”

Why would disclosure of the donors funding certain speech have the effect of shutting down that speech? Because of what can happen to donors when some of the more radical elements of our body politic learn who’s funding the speech they oppose. Ask donors to the National Organization for Marriage (NOM) what happened when NOM’s tax returns – which included personal information about major donors were leaked to its political opponents in 2012.

Whitehouse’s purpose is clear: He wants to force public disclosure of donors to shut down the political speech they fund. He believes that by forcing disclosure of their personal information, he will scare off many of them from funding political speech. For him, this effect is not a bug, but a feature. And he may well be right.

His effort is literally anti-American.

Anonymous political speech has a grand and storied tradition in the United States. Just look at the debates over ratification of our Constitution at the very birth of our nation. Three of our key Founding Fathers – Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay – wrote and published some of the most important and influential documents of our nation’s founding, collected later as “The Federalist Papers,” while hiding behind the pseudonym Publius. They wanted their arguments in favor of ratification of the Constitution to be considered on their own merits, and they wanted their audience not to be influenced by their perceptions of the authors.

The Supreme Court of the United States, too, has recognized another legitimate reason for donors to remain anonymous from state scrutiny. In the landmark 1958 NAACP v. Alabama case, the Court ruled that the state of Alabama had no authority to require the state chapter of the NAACP to hand over a membership list. “Immunity from state scrutiny of petitioner’s membership lists,” wrote Justice John Marshall Harlan II, “is here so related to the right of petitioner’s members to pursue their lawful private interests privately and to associate freely with others in doing so as to come within the protection of the Fourteenth Amendment.” So First Amendment rights to freely associate and Fourteenth Amendment rights to due process prevailed over the state’s desire for information about a group’s supporters.

As I consider this legislative battle, I can’t help but wonder which part of Justice Harlan’s argument Whitehouse does not understand. And – perhaps more pointedly – how does he feel about carrying forward the mantle, almost seventy years later, of the Alabama thugs who tried to use the coercive (and unconstitutional!) power of the state to destroy the state’s chapter of the NAACP as it struggled to defend its members’ civil rights?