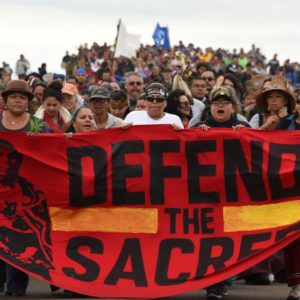

An activist report on the social costs of the Dakota Access Pipeline wants to help resource development companies understand the risks they can incur by ignoring the human rights of indigenous peoples, according to the lead author.

But would those costs have been incurred had the widespread protests from environment activists not taken place? That’s a question raised by industry analysts and a coalition of groups – including labor groups – that work in the energy sector.

The report, “Social Cost and Material Loss: The Dakota Access Pipeline,” was published by the First Peoples Investment Engagement Program. It looked at stock prices for Energy Transfer Partners (ETP), the company overseeing the project, operating and protest costs, as well as the costs to community stakeholders. The report also highlights the “lack of meaningful consultation” between ETP, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, whose tribal land the pipeline would come near.

“Overall, indigenous peoples are still really trying to come out of colonization and really have their rights to their lands, territories, and resources be respected in a way that’s more in alignment with human rights,” said Carla Fredericks, director of the American Indian Law Clinic and primary author of the case study.

According to the paper, the tribe spent three years communicating its opposition to the pipeline. Fredericks said this was mostly letters and emails as opposed to conversations. She said EPT assumed it was clear to proceed once it had permits from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers but that the tribe viewed the area as unceded land. The land the pipeline was installed on is nearly exclusively privately owned, and the project did not enter the Standing Rock Sioux reservation at all, according to a fact-checking page by Energy Transfer LP.

“What we showed in the case study was that had they listened to the tribe back in 2014, they wouldn’t have found themselves in this unfortunate position of creating significant losses for their shareholders,” Fredericks said. “Companies stand to lose a lot of money where there’s social uprising. I’m not sure the industry wants this conflict.”

The report looked at the stock price on Aug. 3, 2016 – trading at $30.15 a share – when project-level financing was announced. It notes that a year later, it dropped to $19 a share and that the S&P value was down by almost 20 percent during roughly the same period as the protests kicked up steam.

But Dan Kish, a senior fellow at the Institute for Energy Research, said the report is making the classic blunder that correlation implies causation.

“I think they’ve cherry-picked the timing,” Kish said. “That was a particularly bad time for pipelines – there was a downturn in oil prices. The fact of the matter is, once pipelines are up and running, they make a lot of money and the people who invest in them make a lot of money.”

More than cherry-picking stock prices, though, Kish said the social costs the report claims made the pipeline significantly more expensive and perhaps prohibitive to the company’s bottom line, are a self-fulfilling prophecy.

“What they’re saying is that the sorts of activities they support – stopping pipelines, stopping energy development and infrastructure projects – turn out to be more costly because the very activities they engage in,” Kish said. “This is a social sciences project, and it reads like one. It’s like a bunch of kids running around saying, ‘Look at all the windows we broke by throwing rocks at them.’”

Among other costs the report claims leads to its conclusion that the pipeline’s true cost is in excess of $7 billion are travel expenses, food and supplies, and missed work by protestors; waste management costs Standing Rock Sioux incurred that will cut into the services it provides tribe members; and legal costs for demonstrators who were arrested; and increased costs for law enforcement.

The coalition Grow America’s Infrastructure Now threw cold water on the claim that protestors picked up any costs, pointing to more than 250 GoFundMe campaigns totaling more than $8 million and other crowdsourcing platforms that raised more than $11.2 million for activities before and after the protests, including tattoos. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers spent $1.1 million to “clear trash, waste, and other debris from the anti-pipeline camps.”