There’s plenty of wrangling in Congress right now regarding potential changes to America’s corporate tax code. The corporate tax rate currently stands at 21 percent. However, Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.V.) prefers a 25 percent rate, while President Joe Biden is aiming for 28 percent. Regardless of the rate, though, Congress must still address an overlooked problem: Plenty of larger U.S. multinational corporations are continuing to avoid paying their fair share of taxes.

Corporate tax reform is obviously a thorny issue. But several of America’s largest tech companies just came out in favor of Biden’s suggested 28 percent rate. Through a partnership with the brand-new “Chamber of Progress,” Amazon, Google, and Facebook have jointly offered support for Biden’s proposal. It’s a nice gesture on their part, but rather hollow—since they’ll hardly be affected by any tax increase.

Last year, the Coalition for a Prosperous America (CPA) published a report showing U.S. multinational corporations paid an average of only 8.7 percent in corporate taxes in 2019—far less than the current 21 percent rate. Large tech companies remain some of the prime beneficiaries of this tax avoidance since they repeatedly shift much of their profits to Bermuda and other tax haven nations.

Amazon is a perfect example. The e-commerce giant paid zero state or federal taxes in 2018 despite earning more than $11 billion in profits. While enjoying massive revenues, Amazon simply took advantage of current tax loopholes—and assigned much of its profit to low-tax countries outside of the U.S.

When companies like Amazon shift profit abroad, they shrink the available U.S. tax base. And so, it’s somewhat disingenuous for them to support the 28 percent Biden tax proposal—since it will hardly affect their bottom line. Essentially, if Congress votes to raise America’s corporate tax rate by 7 percent—but doesn’t simultaneously address tax avoidance—multinational corporations would likely face only a small increase. However, domestic companies would have to carry the full amount.

Gaming the system like this offers a competitive advantage. Amazon paid a mere 4.3 percent average tax rate over the last three years while competing with thousands of brick-and-mortar retailers across the country. If the U.S. corporate tax rate climbs to 28 percent, these Main Street businesses will bear an outsized portion of the increase—not Amazon.

Concerns about such tax disparities aren’t new, though. The Coalition for a Prosperous America estimates that multinationals avoided paying $97.8 billion in corporate taxes in 2019. In response, the Biden administration has even offered some potential solutions through its ‘Made in America’ tax plan. However, the complexity of these proposals could make them unwieldy and hard to sell in Congress.

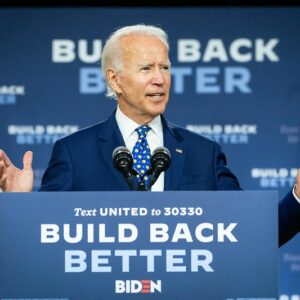

What’s needed is simplicity and equity. Since Biden’s ‘Build Back Better’ plan aims to strengthen domestic U.S. manufacturing, it’s time to implement a system that fully taxes all multinational companies. The logical answer is to adopt a system of “Sales Factor Apportionment” (SFA) in order to impose taxes specifically on the location of a company’s final sale. That means, if a company generates $1 billion of profit on its U.S. sales, it should pay U.S. corporate taxes on that $1 billion. No more convoluted profit calculations—or claiming residence in an obscure, offshore location—in order to skirt U.S. tax obligations.

America’s large tech companies are among the multinationals that keep dodging a full tax load. It’s somewhat meaningless, then, that they appear to be supportive of a tax hike. In reality, their main goal is to prevent anything that would include more of their profits in the U.S. tax base.

The American people already recognize that it’s unfair for multinational firms to sell products in the U.S. market but pay little or no federal taxes. That includes the tech firms that consistently generate massive profits from U.S. consumers. It’s time to shift to an SFA system that closes loopholes and ensures that all companies pay their fair share of taxes.