SEOUL — In all the outpouring of high praise for the Korean blockbuster “Parasite” after its dazzling success at the Academy Awards ceremony in Hollywood, one noteworthy side of the production was largely ignored: the film had the enthusiastic backing of an heiress to the riches of Korea’s biggest commercial dynasty, the Samsung empire.

The fact that Mi Kyung-lee, widely known as Miky, vice chairwoman of the CJ Group, in charge of its entertainment division, threw her power and influence behind this project is a remarkable reflection on two aspects of an incredible undertaking.

The first is that Miky was born to riches but left unspoiled by the fortune that was hers as the granddaughter of Lee Byung-chul, the Samsung founder, who probably never envisioned any of his sprawling holdings morphing into mass culture on stage and screen.

The effervescent Miky, if she was going to invest in popular movies, might have been expected to prefer propaganda epics venerating great moments in Korean history or the lives and loves of Koreans in a dynamic, high-powered society. Violence is often a characteristic of such films, directed at audiences that revel in sometimes balletic deeds of derring-do, but critical bludgeoning of the established order, of the moneyed elite, is rare.

There is violence aplenty in “Parasite,” all to illuminate the biting social satire that claws into the very society that Miky might have chosen to uphold. No way, however, was she bound by her wealth and upbringing to throw her fortune behind a work that might in the end defend the status quo.

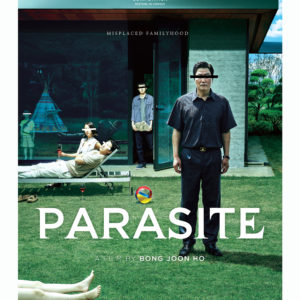

At the apex of a long career dedicated to building CJ into Korea’s biggest entertainment complex, she was totally behind Bong Joon-ho, the brilliant director who picked up two individual awards, the first, with Han Jin-won, for best original screenplay, the second as best director.

Those trophies were the prelude to the two top prizes, best international film and, the climatic finale to the four-hour program, best film, period.

There is also another lesson here. Easy though it is to criticize the system in which Korea’s great conglomerates, or chaebol, led by Samsung, Hyundai, SK and LG, dominate the Korean economy, it’s hard to deny they also have the potential for encouraging, financing, defending the artistic freedom needed for a free, democratic society to thrive. It’s difficult if not impossible for directors to create and produce without the sympathetic support of the likes of Miky Lee.

Bong is just the most obvious example, in the starry aftermath of his triumph at the Academy Awards, of directors, artists and authors who’ve survived in this environment. There are no doubt innumerable instances in which creative figures and forces have been frustrated, inhibited, maybe repressed, but Bong’s success shows that it’s possible not only for him but for others to innovate and create works that are mordantly critical of the system in which they exist.

At the risk of making too obvious a political point, no one can be unaware of the impossibility of producing such satire in China, under the dictate of Yi Jinping, much less in North Korea, in the hands of the third-generation ruler of the Kim dynasty, Kim Jong-un.

Interestingly, Kim’s father, Kim Jong-il, did promote a film industry. In fact, in his youth he established a huge enclave on the outskirts of Pyongyang for making movies. Then, in 1978, he ordered the kidnapping of a famous South Korean actress, Choi Eun-hee, and, a few months later, that of her husband, the director Shin Sang-ok. Together they created “socialist art” for Kim until 1986 when he was confident enough of their loyalty to let them attend the Venice film festival, from which they escaped to the U.S. Embassy.

Great art is not likely to surface within a system that uses it to uphold those in high places. The concept of art for art’s sake, the freedom to criticize and satirize an entrenched elite and a power-hungry ruling clique, are essential. Miky Lee, privileged, highly educated in Korea as well as the United States, Japan and Taiwan, recognized and encouraged that spirit.

About director Bong, she liked “everything” — “his smile, his crazy hair, the way he talks, the way he walks and especially the way he directs,” also “his sense of humor and the fact that he can really make fun of himself and he never takes himself seriously.”

It would be great to think “Parasite” is not an isolated phenomenon, that other directors will also have the freedom, the temerity and the resources to produce distinguished works.

To do so, there must be more types like Miky Lee — living evidence that the chaebol system can produce unsung angels with the confidence and means for aiding and abetting genius when they see it.