In September 1838, America’s greatest storyteller escaped from slavery. On September 22, 1848, he shared one of his greatest lessons. Today, in an era of often-ugly political and online discourse, let’s follow his lead.

Disguised in broad daylight as a sailor in a red shirt, black tie and tarpaulin hat, Fred Bailey waited nervously for a train at the Baltimore station. Anna, his fiance, held him close. She sold her bed, according to family lore, to help him purchase a ticket. In his pocket, Bailey held a retired sailor friend’s identification and papers to present at several checkpoints. With tears in his eyes, he hugged and kissed Anna, not knowing whether he’d see her again.

According to historian David W. Blight, Bailey “jumped on the crowded negro car and began the most famous escape in the annals of American slavery.” His friend Isaac ran up alongside the moving train to hand Bailey his baggage, including his prized possession: a book of famous speeches. Bailey headed northeast to an unknown future.

Later, he wrote, “No man can tell the intense agony which is felt by the slave, when wavering on the point of making his escape. All that he has is at stake. … The life which he has may be lost, and the liberty which he seeks may not be gained.”

Traveling through slave states, Bailey handed his papers to conductors and fielded questions from a young boat worker about his sailing past. His heart surely sank as he saw a powerful man who knew him. The man took no notice. A blacksmith recognized him but kept silent.

The fugitive left his train in Wilmington and took a steamboat up the Delaware River. He stepped off in Philadelphia and stood on free soil. The next morning he arrived, awestruck and alone, on the crowded streets of Manhattan.

Within weeks, Bailey would reunite with Anna, marry her, and change his name to Frederick Douglass.

When Douglass spoke, people listened — enthralled. Journalist William Lloyd Garrison called Douglass’ first formal speech as a fugitive “extraordinary,” writing that he was “richly endowed” with intellect and “more eloquent” in the cause of liberty than even the Founding Fathers.

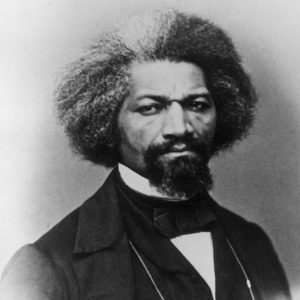

Douglass used his voice and pen to spread his stories like wildfire, altering the landscape of countless minds and, eventually, the world. He became the most photographed American of the 19th century, and among the most traveled and influential.

Ten Septembers later, Douglass penned his famous open letter to his former slave master, Thomas Auld. The man who made Douglass feel like “a poor, degraded chattel — trembling at the sound” of his voice. The man who tied Douglass’ cousin Henny, a crippled girl, to a joist and savagely beat her, then left her to hang for several hours dripping blood onto the floor before returning to beat her again.

If you were Douglass, what would you say to Thomas Auld? Douglass used his stories to make us see and feel the folly of slavery. Crucially, he concludes:

“There is no roof under which you would be more safe than mine, and there is nothing in my house which you might need for your comfort, which I would not readily grant. Indeed, I should esteem it a privilege, to set you an example as to how mankind ought to treat each other.

“I am your fellow man, but not your slave, Frederick Douglass.”

Douglass knew it is not enough to express outrage and righteous indignation. To make the world better, we must show with clarity and compassion the correct path forward.

He fought, yet transcended outrage. He felt privileged to read and think for himself. He loved technology, but not at the expense of what matters most. He made his ideas clear and practiced to ensure that people understood and felt them. He mastered the art of telling his own story. And he showed that regardless of how people treat us, we have the freedom to choose how we treat them.

Imagine if we all took his approach — even with those who cause us suffering — and how our daily, and digital, lives would improve. We too can choose to transcend outrage, build our minds and voices, and show with clarity and compassion the correct path forward.

Today, with Douglass as our guide, let us set a modern example as to how we ought to treat each other.