It’s a reality of life. After well-known people pass away, the vast majority tend to eventually fade from public memory. Eventually, most are reduced to — if they are lucky — at least a few factoids.

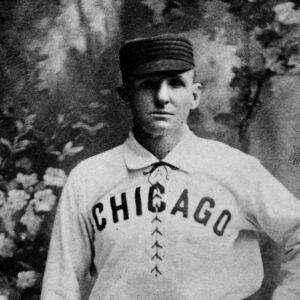

In sports, few major athletes illustrate the reality as starkly as Adrian “Cap” Anson, who died in Chicago 100 years ago on April 14. Nowadays, baseball history and trivia buffs may comprise the only sizeable chunk of us who can rattle off his big achievement: reaching 3,000 hits. He was the lone player to do so before 1900.

Racial history aficionados do like to keep his memory alive. His opposition as a player-manager, during his big-league career, to playing against teams with Black players was at least symbolically significant. He can be safely said to have reinforced the “color line” in the National League, the most prominent major league of the 19th century.

In 2020, Washington Post columnist Kevin Blackistone complained to the National Baseball Hall of Fame’s museum that it was largely silent about Anson’s great negative influence. In response, the Hall of Fame added prose, although not — as Blackistone recommended — directly to Anson’s plaque. One insert describes Anson as “influential” on curtailing the presence of Blacks in professional baseball. Another states that his drawing of a “color line thwarted Black athletes for some 60 years,” until the advent of the first 20th-century Black major leaguer, Jackie Robinson in 1947.

That falls short of rehashing a speculative claim that Anson directly led the top minor league of the day, the International League, to stop approving contracts with Black players. There were more obvious, and contemporarily reported reasons, for its decision.

Also speculative is that because of his stature, Anson, as Chicago’s player (captain)-manager for 19 years, had lots of racial influence. Actually, Anson, who was bluff and gruff, was not personally popular among his peers. Although some historians cite, as proof of Anson’s great influence, early 20th-century argumentation by Black player-turned-writer Sol White, the newspaper record undercuts some of White’s central allegations.

Also in 2020 after hearing from Blackistone, the Hall of Fame added this sentence to its exhibition prose: “Many credit the future Hall of Famer for helping to save the game when its fate in the late 1870s was in doubt.” Baseball historian Bill James had laid out such a case in a 2001 book.

The National League, the dominant major league of that era, had suffered a huge blow when four Louisville National League players were found to have taken bribes to lose games purposely in 1877. In contrast, in the 1880s and 1890s, Anson became just about the most prominent player who stood against the influence of professional gamblers. (Also in those decades, sustained good attendance at Chicago home games, when the mostly Eastern teams needed to offset their travel costs, was arguably a key to the league’s financial success.)

The notion that a racist could have been a major symbol in elevating baseball over one of its biggest evils might be surprising today. Yet Anson even did so while betting frequently on the sport in the last half of his career. Ignoring the postseason, I found him making 57 regular season bets. But unlike 1960s-to-1980s star Pete Rose, who was permanently banned from election to the Hall of Fame in 1989, Anson bet only for his team to do well, and mainly on its season performance overall.

At a then-tall 6 feet, Anson also helped make baseball a spectacle by berating the often-lone umpire, in a booming voice that fans could apparently easily hear, in much smaller ballparks than today. And he could be constantly observed. That’s because between innings, players were not disappearing into dugouts, which had yet to be invented. Meanwhile, many sportswriters were applying a Victorian Era touch that focused on mannerisms, in a way that female non-fans probably enjoyed. His 3,000th hit passed with little notice.

If interest should be revived in the sport’s most colorful figures regardless of era, Anson, for having chewed up lots of scenery — including off the field by leading his team to many games in horse-drawn carriages — would be hard to top.

But perhaps the baseball gods were onto something when they came up early this century with a Jackie Robinson Day every April 15. That’s because few players come as close as Anson, via his birthday (April 17) and death (April 14), to wrapping around it.