What is it about Donald Trump, twice divorced, serial adulterer, loud-mouthed braggart, bully and liar, that appeals so deeply to America’s evangelical Christians?

They’re ultra-religious, willing to sit though endless sermons and join in loud and fervent prayer, and yet they voted in overwhelming numbers for a president who rarely went to church, did not participate in religious groups or charities, had no evangelical affiliation and probably could not recite the Lord’s Prayer without a hasty rereading of those hallowed words to be sure of not mangling the lines.

Why was it that upward of 80 percent of evangelicals voted for him last November and, mostly, remain true to him today in the face of criticism, and worse, from some Republicans as well as Democrats?

That’s a question to which Koreans in particular might want an answer considering the deep faith of millions, the rapid growth of their churches and, of course, the conservatism that imbues many of them. Koreans in evangelical congregations such as the Full Gospel Church, whose hundreds of thousands of followers flock every Sunday to seven services in the imposing domed structure near the National Assembly, comprise the world’s single biggest Christian parish, might appreciate the messianic appeal. Here’s a man who not only challenges politically correct intellectualism but at heart opposes what they oppose, including gay marriage, abortions and the freedom of leftists to protest established law and order.

Trump may be a sinner, he may be fabulously wealthy, and he may really be on the side of Wall Street rather than Main Street, but American evangelicals also see in him the figure who defeated the representative of respectable Protestantism, Hillary Clinton, raised as a Methodist in an upper-middle-class environment.

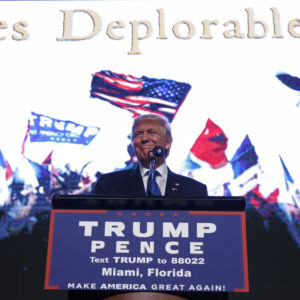

To evangelicals, Trump represented a breath of fresh air, relief from the affectations and hypocrisy of a super-educated, moneyed elite, many of them seen as pretentious liberals. To them there’s no hiding how these snobs felt about the great unwashed — millions of Americans who felt they’d been tricked, fooled and exploited by people who saw them as social, cultural inferiors.

In understanding the affair between Trump and evangelicals, I’ve visited evangelical congregations in both the United States and Asia. Who would not be impressed by the crowds that swarm these churches, by their enthusiasm for the teachings of their pastors, their love for religious rock and roll that replaces the stately traditional hymns to which members of socially superior churches are accustomed.

It’s often noted that Trump found his greatest wellspring of support in Midwestern and Southern states where evangelism has taken root more deeply than elsewhere in the country. Journalists gave short-shrift to the flyover states that typically America’s taste-makers fly over on the way from the east to the west coast and back again. They also clearly underestimated the power of evangelism in the Southern states, where racial prejudices date from centuries of slavery, the Civil War of the 1860s and its long aftermath.

There is a distinct relationship between evangelicals and the bullies responsible for the tragedy at Charlottesville, home of the prestigious University of Virginia, where they massed in bloody demonstration against removal of a monument honoring Robert E. Lee, the defeated general of the rebel army of the Confederacy.

It was for that reason that Trump aroused outrage on all sides by placing the blame for the tragedy at Charlottesville on both sides rather than condemning the neo-Nazi proclivities of fanatics responsible for a protest reflecting bigotry and outrage over the removal of the image of a figure remembered by many Southerners with reverence. Trump further fed their prejudices by saying that he did not agree with the trend for removal of the statues of other Confederate leaders, still regarded as heroes to those mourning the lost flower of the Old South.

Trump’s tweets may have aroused global outrage, but it’s certain his popularity endures among evangelicals, who see him as representing their hopes and aspirations despite the contradictions inherent in his tax bill and so many other measures that he’s attempting to ram through a reluctant Congress.

At the heart of his popularity is class warfare in which evangelicals clearly rank lower on the social scale than traditional Protestant religions, notably the Episcopalian or Anglican faith. Yes, he’s technically a Presbyterian, but it’s easy to ignore that reality while convinced that he offers hope and opportunity for millions of evangelicals who feel oppressed by their social betters.

Trump also taps into another vein among evangelicals. His scheme for sealing off America’s southern borders with Mexico and expelling millions of “illegals” appeals to those who see the new arrivals as competing for their livelihoods, crowding their schools, adding to the crime rate. It’s easy for evangelicals to blame their distress on the influx of Hispanics and Latinos.

As Trump’s overall popularity rating sinks to record lows and members of his own Republican Party disavow his leadership, however, he obviously faces trouble from enemies whom evangelicals look on with suspicion if not hatred. Can he survive his four-year term without facing impeachment or will he overcome obstacles and position himself for a second run in 2020?

Whatever happens, he counts on a bedrock of support from American evangelicals to whom his populist rants and tweets cut to their frustrations in a system that many blame for their exclusion from the riches of an elite that holds Trump in deepest disdain.