On April 2, Maryland prison officials confirmed its first three COVID-19 cases, one inmate and two staff members. Maryland Gov. Larry Hogan previously stated he had no coronavirus plans for incarcerated individuals — saying inmates are “safer where they are.”

The governor’s comments and lack of an action plan concern me from a public health and criminal justice viewpoint. In March, New York City confirmed 39 inmates and 21 Department of Corrections staff tested positive for the virus. In just 12 days, New York’s Rikers Island cases went from one to 200.

Like New York, Maryland will likely soon become inundated with COVID-19 in its prisons, youth detention centers and jails.

As we know from social distancing, movement drives the pandemic. Corrections officers and prison medical and other staff go back and forth to the community. In traveling to and from work, they will likely bring the virus to others living outside prison walls.

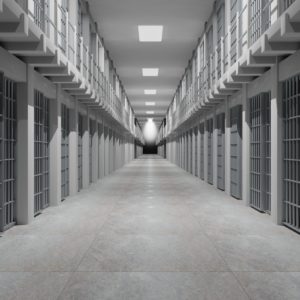

And prisoners cannot self-isolate.

Penal institutions are a “breeding ground” for the coronavirus, much like cruise ships, nursing homes, college dormitories and schools. A cell meant to hold one inmate may often hold three. There is no way that an inmate can engage in social distancing of less than six feet.

And hand sanitizer is prohibited in most penal institutions due to alcohol content. On March 25, over 200 Johns Hopkins University public health professionals wrote to Gov. Hogan to express their urgent concerns and address precautions to prevent COVID-19 from spreading in jails, prisons and youth detention centers.

Other jurisdictions have made changes.

Los Angeles the nation’s largest jail system, trimmed its population by releasing individuals with less than 30 days on their sentence. California stopped all transfers of new inmates at state prisons for 30 days. California also plans to release 3,500 non-violent prisoners in the next 60 days.

Colorado Gov. Jared Polis issued guidance on reducing the number of persons in jails — resulting in a 43 percent decrease in jail population in one county. Wisconsin Gov. Tony Evers also stopped admission of new inmates or prison transfers to stop the spread of COVID-19.

U.S. Attorney General William Barr issued federal guidelines for older, medically vulnerable inmates to be considered for home confinement with regular check-ins. Democrats on the House Judiciary Committee urged Barr to release as many inmates as possible — including pregnant women — due to coronavirus outbreaks.

We must balance public health, public safety and criminal justice in weighing options to address COVID-19 in penal institutions. There are many persons in jail awaiting trial who should be immediately released.

As a former Baltimore prosecutor, I recall persons awaiting trial on misdemeanor nonviolent charges who are unable to make a small 10 percent bail bond amount of $100 on a $1,000 bail. Others charged with nonviolent crimes often remain in jail due to technical violations.

Technical violations may include alleged violations of probation or parole for failure to pay a fine, failing to report an address change, testing positive for an illegal substance or missing an appointment with a probation/parole officer. Some persons remain incarcerated with less than six months remaining on their sentence.

Non-violent misdemeanor defendants, those in jail for technical violations, those being detained on small cash bail amounts and those with six months left on their sentence should be released immediately.

Those inmates who no longer pose a threat or risk to society, due to age and/or health conditions should also be released — even if the original sentence was one of violence.

Our elected officials, judges, prosecutors, defense attorneys and public health officials must work together to prevent rampant spread of the virus in jails and prisons.

We must act now to prevent widespread harm to those individuals inside and outside of prison walls.