The assumption is that we’ll return to work when COVID-19 is contained, or we have adequate vaccines to deal with it.

That assumption is wrong. For many millions, maybe tens of millions, there will be no work to which to return.

At root is a belief that the United States — and much of the world — will spring back as it did after the 2008 recession: battered but intact.

Fact is, we won’t. Many of today’s jobs won’t exist anymore. Many small businesses will simply, as the old phrase says, go to the wall. And large ones will be forced to downsize, abandoning marginal endeavors.

When we think of small businesses, we think of franchised shops or restaurants and manufacturers that sell through giants like Amazon and Walmart. But the shrinkage certainly goes further and deeper.

Retailing across the board is in trouble, from the big-box chains to the mom-and-pop clothing stores. The big retailers were reeling well before the coronavirus crisis. Neiman Marcus, an iconic luxury retailer, has filed for bankruptcy. All are hurt, some so much so — especially malls — that they may be looking to a bleak future.

The supply chain will drive some companies out of business. Small manufacturers may find that their raw material suppliers are no longer there or that the supply chain has collapsed — for example, the clothing manufacturer who can’t get cloth from Italy, dye from Japan or fastenings from China.

Over the years, supply chains have become notoriously tight as efficiency has become a business byword.

Some will adapt, some won’t be able to do so. A record 26.5 million Americans have sought unemployment benefits over the last five weeks. Official unemployment numbers have always been on the low side as there’s no way of counting those who’ve given up, those who work in the gray economy, and those who for other reasons, like fear of officialdom or lack of computer skills, haven’t applied for unemployment benefits.

To deal with this situation the government will have to be nimble and imaginative. The idea that the economy will bounce back in a classic V-shape is likely to prove illusory.

The natural response will be for more government handouts. But that won’t solve the systemic problem and will introduce a problem of its own: The dole will build up dependence.

I see two solutions, both of which will require political imagination and fortitude.

First, boost the gig economy (contract and casual work) and provide gig workers with the basic structure that formal workers enjoy: Social Security, collective health insurance, unemployment insurance and workers’ compensation.

The gig worker, whether cutting lawns, creating websites, or driving for a ride-sharing company, should be brought into the established employment fold; they’re employed but differently.

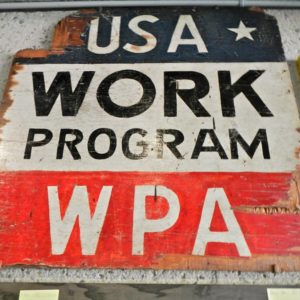

Second, a new Works Progress Administration should be created using government and private funding and concentrating on the infrastructure.

The WPA, created by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1935, ended up employing 8.5 million Americans, out of a total population of 127.3 million, in projects ranging from mural painting to bridge building.

Its impact for good was enormous. It fed the hungry with dignity, not the soup kitchen and bread line, and gave America a gift that has kept on giving to this day.

Jarrod Hazelton, a Rhode Island-based economist who’s researched the WPA, says the agency gave us 280,000 miles of repaired roads, almost 30,000 new and repaired bridges, 600 new airports, thousands of new schools, innumerable arts programs, and 24 million planted trees.

It also enabled workers to acquire skills and escape the dead-end jobs they’d lost. It was one of the most successful public-private programs in all of history.

As the sea levels rise and the climate deteriorates, we’ll need a WPA, tied in with the Army Corps of Engineers, to help the nation flourish in the decades of challenge ahead. The original was created by FDR with a simple executive order.