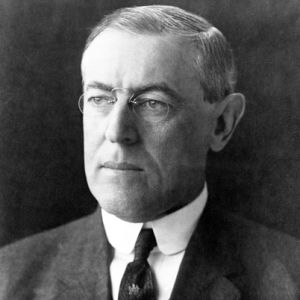

As Princeton undergraduates, we didn’t call it the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs. It was just “Woody Woo.”

Beneath the jocular nickname, however, we had a deep — but unthinking — respect for our former president.

It couldn’t be any other way. Wilson’s name and legacy were omnipresent — the prestigious Wilson School, a residential college, academic awards, frequent appearances in campus lore and traditions. Even a gargoyle on one of the Collegiate Gothic buildings bears his image, or so the legend says.

Wilson was a visionary who transformed Princeton from a sleepy male finishing school into a distinguished academy. His innovative teaching methods, rigorous curriculum and dedication to turning “thoughtless boys” into “thinking men” set high standards for his own and future generations.

Wilson was as much a part of the fabric of campus life as Nassau Hall, where the Continental Congress once sat, or F. Scott Fitzgerald, who found his literary voice dreaming among the “spires and gargoyles” of Princeton then went on to write “The Great Gatsby.”

For Princeton to abandon Wilson was A Big Thing.

And yet, now that it is done — the Board of Trustees voted to change the names of both the school and the residential college on June 26 — it seems so obvious. After all, Wilson’s racism was not just a quirk of his nature — a shadow to overlook in the glow of his greatness — but a fundamental value that underlays who he was.

At Princeton, Wilson worked hard to keep black students from being admitted.

In Washington, within a few months of his assuming the presidency in 1913, his Cabinet members were segregating federal departments and firing black employees. This not only reversed years of progress but gave the lie to Wilson’s campaign pledge of “absolute fair dealing” for blacks.

In the public sphere, Wilson used his prominence as a historian to spread lies about Reconstruction and entrench an ideology of white supremacy that continues to haunt us today, celebrating the murderous Ku Klux Klan as “a veritable empire of the South, to protect the southern country.”

This quote from Wilson’s masterwork, “A History of the American People,” was even used on a title card in the film “Birth of a Nation” to lend authority and credibility to its evil fantasy of rapacious freedmen conquered by white warriors on horseback.

Wilson returned the compliment by screening the film at the White House.

Yes, Wilson supported some noble goals — among others, the vote for women, federal loans for farmers, an 8-hour workday for laborers, and independence for subjugated nations.

But when we honor someone the way Princeton honored Wilson, we set a high bar. Especially in the case of a moralist like Wilson, gutter racism makes the honors hollow.

So the key question for me and my fellow alumni is not why Princeton decided to cut Wilson out of the thick growth of tradition that clings like the ivy to these venerable walls, it’s … what took us so long?