For Part 3 of this series, I want to examine some fundamental elements of the race that will have a very strong influence on what happens in November.

Find the other articles in this series here: Part 1, Part 2, Part 4, Part 5, and a brief update. And the final update—Why Joni Ernst will be the next US Senator from Iowa.

While Democrats are projected by the model presented yesterday to slip more than Republicans in registration, the simple fact about turnout is that it is habitual. Once someone starts voting, he or she tends to continue. Additionally, no-party voters often lean toward a particular party cycle after cycle. This is the problem that confronts Republicans this year. For the prior two presidential cycles, the Obama campaign proved remarkably effective not only registering but also turning out their supporters—both Democrats and no-party voters. This leaves Republicans with an uphill battle.

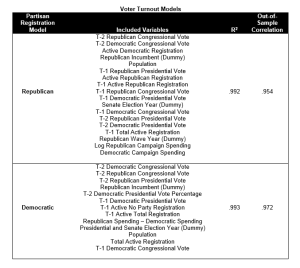

In order to evaluate the likely turnout in the 2014 Senate race, I developed models similar to those for registration, using step-wise linear regression on county-level turnout. The two partisan models below proved very accurate in the out-of-sample testing. A wide range of historical data was used. As with the registration model, only data known prior to the election can be used in predicting turnout. The model focuses heavily on lagged turnout and registration for each county, which is expected based on the habitual nature of voting. Where the model becomes more complicated is in the use of variables that fluctuate up until Election Day, specifically registration and campaign spending. These variables and the likelihood of other potential inputs create a universe of possibilities, the most likely of which have all been tested in the model.

Particularly important to note in these models is that Iowa polling numbers are not used. There is simply no reliable way that polling can be used in such a model. There have been no competitive Senate races in Iowa in thirty years. Historical polls for House races present too broad an array of challenges, and voters are typically too unfamiliar with candidates for an open seat even up until Labor Day in order to feel confident in poll numbers. I feel far more confident in the model without polling than if it were included. Polling bears a strong relationship to the variables included in the model, and even if it were possible to have tested polling as a potential variable, it’s very likely it would not have been included in the final model because of collinearity with the other variables, such as Cook Report ratings.

The predictions produced by these models paint a frightening picture for the Republicans running for Senate. There is a very limited set of possible scenarios that would allow a Republican to win. The reasoning behind this statement is based on two sets of variables above that may ultimately determine the outcome of the 2014 Iowa Senate election: current registration and campaign spending. Fortunately for the GOP campaigns, these are the areas where they can actually have an influence over the vote. I will address each in turn below before we examine the projections of the model on Friday.

Can Campaigns Influence Registration?

It is necessary to return again to the topic of registration in the context of the turnout model. While we know the values of any lagged variables in the dataset, the variables for current active registration will fluctuate all the way to Election Day. The GOP turnout model includes variables for current active Democratic and Republican registration. The Democratic model uses only total current active registration.

Registration may seem like a lever that campaigns should be able to actively influence. Field staff and volunteers on a campaign spend much of their time trying to get new voters registered. The Obama field operation is particularly noteworthy for its success registering voters. So it would seem logical that campaign spending is closely related to the number of registered voters.

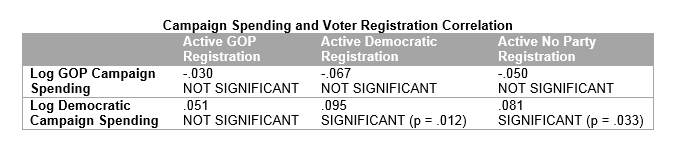

But this data does not indicate that is the case. In the registration model discussed earlier, campaign spending was not a predictive factor. This point is explored further in the table below. Campaign spending shows almost no correlation to registration. This is a surprising revelation, and the best explanation that can be provided may be that registration, as previously discussed, is reliant on demographics and macro-level conditions and may be beyond a campaign’s control.

This data should not stop Iowa campaigns from trying to register voters. It is quite possible that Iowa faces unique political conditions that cause the effects of spending on registration to not show in the data. The problem may be in how campaigns have worked to register voters in the past. In this election cycle, campaigns using consumer-level data and conducting field experiments could target individuals not currently registered but highly likely to vote in a very cost-effective manner. That would change these findings entirely.

And as will be discussed below and on Friday, money will have a tremendous influence on this election, even if we cannot be certain it will influence registration.

For the Love of Money

One of the most important questions to examine in the Iowa Senate race is money. As of the end of the first quarter, the Braley campaign had raised over $5.25 million, with $3.1 million cash on hand. Iowa political insiders expect Braley to be able to raise in excess of $10 million before the November election, with the possibility or raising $12 million or more if the race becomes competitive. Republican campaigns, on the other hand, are struggling with fundraising. Joni Ernst, the candidate favored by many party insiders, ended the first quarter with total receipts of $740,000 and only $427,000 cash on hand.

Some Republicans’ believe their saving grace financially may be Mark Jacobs, a former Wall Street executive and energy CEO. He has raised $2.37 million, which is primarily comprised of his own money, and he has outspent Ernst 10-to-1 in the primary. That said, monetary advantage can be negated by poor-quality candidates, and Jacobs has faced significant opposition research, including questions over Reliant Energy’s decline under his leadership.

The question to consider in the data is how much money actually matters. Does it really give Braley a significant advantage, and what impact will it have on a poorly funded GOP campaign. Money is essential to building a campaign operation, getting out the message, and turning out supporters, but does an extra dollar have a real impact?

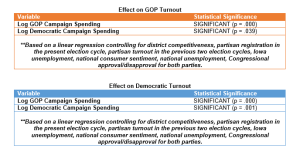

To answer this question, I examined spending (in 2012 dollars) in Iowa congressional campaigns dating back to 2000 and looked at the impact on county-level turnout. A natural log was taken of the expenditures to reflect diminishing returns on investment. It’s necessary to use data on Congressional races because there have not been any competitive Senate races. Additionally, the use of Congressional races increases sample size and narrows the geographic region where the money is being spent. While there is not a perfect correlation between Senate and Congressional races in monetary impact, we can expect a very similar effect. Regressions were run on GOP and Democratic turnout, controlling for a range of variables reflecting race competitiveness and past turnout.

It is important that I add a disclaimer that when seeking to isolate monetary effects, it’s possible there may be some spurious correlations and endogenous variables left unaccounted. If the race receives enhanced media attention because of high spending and close polling, all of those factors could likely influence each other and every other aspect of the race.

The data indicate a very strong relationship between campaign expenditures and turnout in both parties. Additional GOP spending has a large positive impact on GOP turnout and a negative impact on Democratic turnout. The reverse is true of Democratic spending. What is important to consider is that partisan spending has a substantially larger mobilization effect than demobilization effect. The greater impact of money is in turning out supporters of a particular candidate than in convincing non-supporters to stay home.

To some extent, economies of scale may be present in Senate campaigns as compared to House campaigns. This could allow the GOP nominee to build an effective campaign operation with fewer dollars than this analysis may suggest is optimal, but the effect is unlikely to be large.

This study pertains only to spending by the campaigns. We could also expect an effect in money being spent by outside groups, such as the party committees and super PACs. It is still unclear what role these organizations will play in the Senate race, and until the Republican primary begins to shake out, it is unlikely any groups will make a commitment to play in Iowa.

Another effect that will likely have a major impact on the race but is challenging to examine in the data is the cross-promotion effect of same-party campaigns. For example, the Branstad campaign will be well-funded heading into 2014, and the GOP Senate nominee may be able to rely on the Branstad field operation to pull a lot of weight in getting out the vote. That said, the turnout model did not show statistically significant effects for the gubernatorial campaign’s presence on the ballot; however, experimental data could be used by the Branstad campaign to bolster other Republicans on the ballot through cross-promotion effects.

Tomorrow, we’ll examine how President Obama’s approval ratings may influence Iowa voters, and Friday, I will conclude the series by explaining what we can expect to happen in November.