With COVID-19, as New Hampshire goes, so goes the nation.

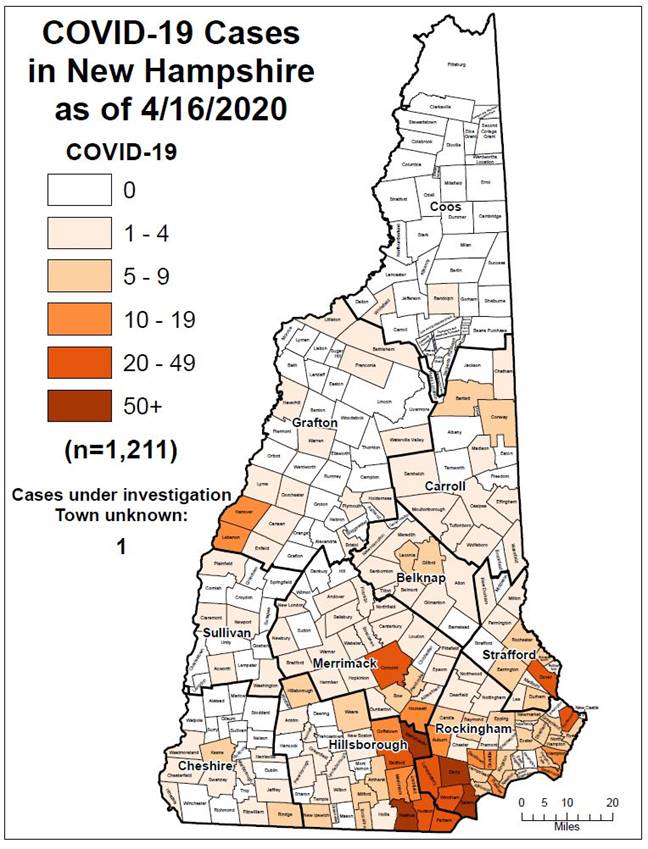

According to the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services, 82.7 percent of those testing positive for SARS-CoV-2 live in Hillsborough, Merrimack and Rockingham Counties. The state’s seven other counties have escaped the worst of the virus.

Source: New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services

Beyond New Hampshire, the story is much the same.

The COVID Tracking Project — an online tool created by the venture-capital firm Related Sciences and journalists with The Atlantic — reports that as of April 16, at 6:12 PM EST, only two residents of Wyoming had died from the novel coronavirus.

The Cowboy State fares best in fatalities, but SARS-CoV-2’s lethality has been light elsewhere, too. Alaska, Arkansas, Hawaii, Idaho, Maine, Montana, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Mexico, North Dakota, South Dakota, Utah, Vermont and West Virginia each have suffered fewer than 50 deaths. Several more states — Delaware, Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota and Oregon — have recorded between 50 and 100 fatalities.

And as the virus continues to impose a brutal butcher’s bill in the tri-state area, New Orleans, and Detroit, the disparity between America’s hardest-hit communities and what many cultural elites consider “Flyover Country” deepens — a phenomenon that is likely to have major implications for the national and New Hampshire economies.

To put the contrast in simplest terms, the Empire State’s mortality ratio is one death per 1,596 residents. (New York City’s comparable figure is 1:771.) In Utah, the ratio is 1:152,665. With rock-bottom smoking and obesity rates, and the youngest median age in the country, the Beehive State’s good fortune is far from shocking.

But Arkansas, hardly a mecca for fitness enthusiasts, enjoys a ratio of 1:81,563. West Virginia, another state that regularly lands near the bottom of state health rankings, fares even better: one death per 137,857 residents. (Given its proximity to the country’s worst hot zone, New Hampshire’s ratio is a quite respectable 1:42,491.)

Move from the state to the metro level, and the heartland’s salutary status persists. Inside Sources maintains a data set of 40 urban areas scattered throughout the nation’s interior — a list that including El Paso, Des Moines, Greensboro, Kansas City, Boise, Little Rock, Knoxville, Cheyenne, and Harrisburg. With 487 deaths, if the sample’s rate were applied to the U.S. as a whole, COVID-19 fatalities would stand at 6,331. That’s a mere 20.5 percent of the actual total.

Last week, the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association, North American Meat Institute, National Pork Producers Council, Brewers Association, Compressed Gas Association, and Renewable Fuels Association sent a letter to Vice President Mike Pence, asking for “temporary, emergency federal assistance” in order to “prevent shortages” of carbon dioxide, a chemical “critical for the operations of food and beverage manufacturers that provide essential goods and services to Americans.”

And the Des Moines Register reports that trade strife had already cratered “corn, soybean, pork and other commodity prices,” and now, “Iowa’s rural economy faces widespread challenges as it battles through the coronavirus crisis.”

New Hampshire’s workforce is significantly more dependent on the manufacturing sector than the nation as a whole. For example, in Sullivan County, where only eight cases of the novel coronavirus have been detected, employment in factories represents well over twice the national share.

So the Granite State is far from immune to what The New York Times called the disruption of “global supply chains,” which has induced “shortages and price increases that are cascading from factories to ports to retail stores to consumers.”

Stay-at-home orders and mandated closure of “nonessential” businesses in the places where so much of the nation’s vital goods originate are not sustainable. For those advocating a speedy return to work, the heartland’s COVID-19 fatality data make a compelling argument.

Even in New Hampshire.