Millions of liberal and conservative parents around the country send their children to public schools every day. But the politics of the organizations that represent teachers’ interests—particularly at the national level—are closely associated with an exclusively progressive political ideology. Experts long active in the upper echelons of education research and policy-making say that the politicization of the teachers’ unions has gotten more intense in recent years. Some say it is because the teachers’ unions are under an unfair assault, others suggest that the internally-democratic structure of the unions make their lobbying platforms susceptible to mission creep. The end result, however, is a Gordian knot of politics and labor battles that have ensconced the teachers’ unions as some of the most powerful and controversial forces in education policy and public policy in general.

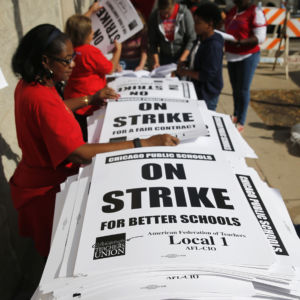

The two largest teachers’ unions are the National Education Association, or NEA, led by Lily Eskelsen Garcia, with nearly 3 million members, and the American Federation of Teachers, or AFT, led by Randi Weingarten, with over 1.5 million members. Through their long histories, the teachers’ unions went though periods where they competed for influence, and others where they flirted with merger. While a merger between the two massive unions is currently not being discussed, the organizations share similar policy positions—for example, they both vociferously opposed the nomination of Education Secretary Betsy DeVos and both overwhelmingly donate to national Democratic political candidates.

“The NEA and the AFT are working closer together than we ever have before,” said Weingarten during a panel discussion alongside Garcia at a March meeting of state education chiefs. During that same panel, Weingarten also said that the two labor leaders’ organizations are back in “war-time” over what they call an assault on public schooling from conservative school choice advocates led by DeVos.

While it is difficult to find daylight between the unions’ policy platforms over the past two or three decades, the two organizations have very different origin stories. The NEA, which dates back to the mid-19th century, was originally a professional organization that represented teachers and administrators. For the better part of its history, (until non-teachers were gradually pushed out in the mid-20th century), the NEA disdained collective bargaining.

The AFT, on the other hand, has its roots in alliances with the early 20th century organized labor movement. These mostly manufacturing unions, particularly active in big cities like Chicago, led sometimes-violent demonstrations for better working conditions. Some elements of the groups that would go on to coalesce into the AFT were historically open adherents of far-left wing political ideologies, including socialism and communism.

Today, the NEA tends to still have a stronger foothold in rural areas, while the AFT generally retains more influence in urban areas, though there are notable exceptions. There are also instances where the local chapters of the AFT and NEA unions have merged, such as in Los Angeles and New York State, while the national leadership remains separate.

Jack Jennings was a longtime lead staffer for Democrats in the U.S. House of Representatives’ education committee and then the founder of the nonpartisan Center on Education Policy, a research group that aims to improve public school quality. In an interview with InsideSources, Jennings observed that the teachers’ unions have increasingly become more concerned with policy issues outside of education and more aligned with the Democratic Party, particularly at the national level.

When he first came to Washington in the late 1960’s, Jennings said that was not unusual to find Republicans who could boast of decent working relationships with the teachers’ unions, though Democrats were, even then, closer to the unions’ interests. By the 1980’s and 1990’s, however, a feedback loop had developed in which the unions would endorse Democratic candidates, angering Republican policy-makers, and pushing the unions further into the left’s arms.

Jennings, who has written against the unions’ practice of endorsing candidates, said it “politicizes the process.” He said, “it’s not good for education because it means that when Democrats are in control the unions at least have someone to talk to. When Republicans are in control, they can’t even get in the door to talk to a secretary.”

Today, national conservatives and the teachers’ unions are openly at loggerheads. In the 2016 election cycle, the NEA spent nearly $27 million, according to OpenSecrets, nearly all of which went to liberal candidates or progressive groups. Similarly, the AFT spent over $19 million in the past election cycle, the lion’s share of which also went to liberal causes. A large number of the volunteers and the delegates at Democratic conventions are often selected directly from the teachers’ unions.

Jennings said that in the 1960’s, 1970’s, and 1980’s he remembers talking to GOP members of Congress who were given policy questionnaires by the NEA, that increasingly asked about social issues like gay rights and abortion. While some Republicans were in line with the NEA on educational issues, the parameters placed on acceptable non-educational positions made earning the unions’ support prohibitively costly, said Jennings.

The NEA’s deeply democratic bylaws are part of the reason why social policy litmus tests were increasingly applied to politicians, he said. At the group’s large conventions, platforms that get taken to Congress are decided by majority-rules votes, which often place leadership—who run for frequent elections—at the whims of their predominately liberal members, said Jennings. (The AFT, on the other hand, has a more top-down structure, and permits longer terms for its leaders.) Political polarization, including the rightward drift of the Republican Party in the wake of political realignment and Newt Gingrich’s Contract with America also contributed to the estrangement of the teachers’ unions and the GOP, said Jennings.

This last argument is particularly appealing to Charles Kerchner, an education policy researcher and professor at Claremont Graduate University in California who has written extensively about the teachers’ unions. He argues that adopting social policy positions does not hurt the teachers’ unions in their advocacy work because they have no hope of working with today’s Republicans to begin with.

“You can’t negotiate with someone who doesn’t think that you are legitimate,” said Kerchner.

While Republicans do not uniformly believe the teachers’ unions are illegitimate, (Kerchner pointed out that on the state level the NEA frequently works well with the GOP), frustration over the strength of the teachers’ unions in national right wing policy circles is real. At an April event at the conservative Hoover Institution, one panelist suggested that conservatives should be prepared to dig in over education policy disagreements for the long haul because “after a nuclear attack, the only thing left will be cockroaches and the teachers’ unions… I say that actually with admiration.”

One of the main complaints from education reformers on the right, and occasionaly among some on the left, centers on the perception that teachers’ unions tend to protect the status quo—including by negotiating strong protections for teacher tenure in collective bargaining agreements. Critics say that these contract provisions make it next to impossible to fire bad teachers, even in the face of clear evidence of incompetence. The popular 2010 documentary, Waiting for Superman, highlighted the problem for mainstream audiences and described how some states spend years shuffling around low-performing teachers from school to school, or worse, pay them full salaries to sit idly in “rubber rooms” while lengthy dismissal hearings are processed.

Al Shanker, the longtime president of the AFT from 1974 to 1997, is famously quoted for defending his hardline stances on teacher protections by saying, “I don’t represent children. I represent teachers… But, generally, what’s in the interest of teachers is also in the interest of students.”

The first part of the quote in particular has provided ample fodder for those seeking to cast the teachers’ unions as intransigent obstacles to reform of the education system. However, Shanker’s long tenure as an influential union boss belies that easy narrative—for example, he was an early backer of charter schools and peer-review evaluations of teachers. He also led the AFT in resisting the formation of a federal Department of Education at the end of the Carter administration, in opposition to the NEA.

In Dana Goldstein’s “The Teacher Wars,” she explains how “Al Shanker is the bridge who links today’s union politics, driven by promises of reform and accountability, to the democratic socialism of the early twentieth century, from which the modern teachers unions emerged.” While Shanker’s early years were rooted in the bare-knuckle hardball tactics of the labor movement, he increasingly became open to evidence-based reforms after baseline benefits for teachers were won.

While the unions have struck some high profile deals in parts of the country to streamline firing processes and to curtail tenure in exchange for pay raises, the debates continue over whether the teachers’ unions and the protections they’ve negotiated for their members have become too powerful.

Richard Ingersoll is a preeminent researcher of national trends in the teacher workforce and a professor at the University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Education. He said that it doesn’t surprise him that the NEA and the AFT’s leadership are joining forces to protect themselves from political attacks, which he said are increasingly coming from academia in addition to conservative commentators.

But many of the criticisms leveled at the unions—that they are the agents of the establishment in education—lack historical context, said Ingersoll. In the late 19th century and early 20th century, as policymakers worked to rapidly expand public school offerings, the system “explicitly borrowed from industry” and recreated a “top-down highly bureaucratized model” to accommodate more students quickly.

Rather than being the impetus for the top-heavy public school system, Ingersoll said that teachers were early victims of it. Controversial protections like the single salary schedule—which are an obstacle to merit pay reforms in some districts—were often originally negotiated to counteract petty corruption among locally powerful principals and superintendents.

“It was a total patronage system. You’d have a superintendent come in and they’d hire relatives and what not to be schoolteachers,” he said. So while benefits like tenure protections are now controversial, Ingersoll worries that the pendulum could swing too far against the unions and the system could revert to one in which teachers are routinely exploited.

Having said that, Ingersoll understands why conservatives view teachers’ unions as an enemy. Because they have increasingly adopted progressive social issues in their advocacy platforms, and because they are increasingly open about their alliance with Democrats, he said that it is understandable that the GOP comes to view them as part of the opposition party.

“If it’s not going to be nuanced and it’s not going to be on the issues, then yes, the other side is going to attack you,” said Ingersoll.