The coronavirus outbreak is wreaking havoc on America’s elections, as evidenced by the fight over Wisconsin’s primary this week.

One proposed solution is moving everyone to voting by mail, but President Trump isn’t a fan. “A lot of people cheat with mail-in voting,” he said last week.

He’s got a point. I’ve done it myself.

In 2011, when I was living in Palm Beach County, Florida, I decided to test the system, and so I asked for three voter registration applications.

I filled them out, listing three different names — two that I pulled out of my head Rebecca Bugle and Hannah Arendt — and my own name, Margaret Menge.

I listed my real date of birth, and made up dates of birth for the other two. On the lines where the application asked for a driver’s license number or last four of social security number, I wrote “none” as the instructions said to do if a person has neither of these.

A few weeks later I got two notices back, saying applications for Rebecca Bugle and Margaret Menge could not be processed because a driver’s license number or social security number was not provided.

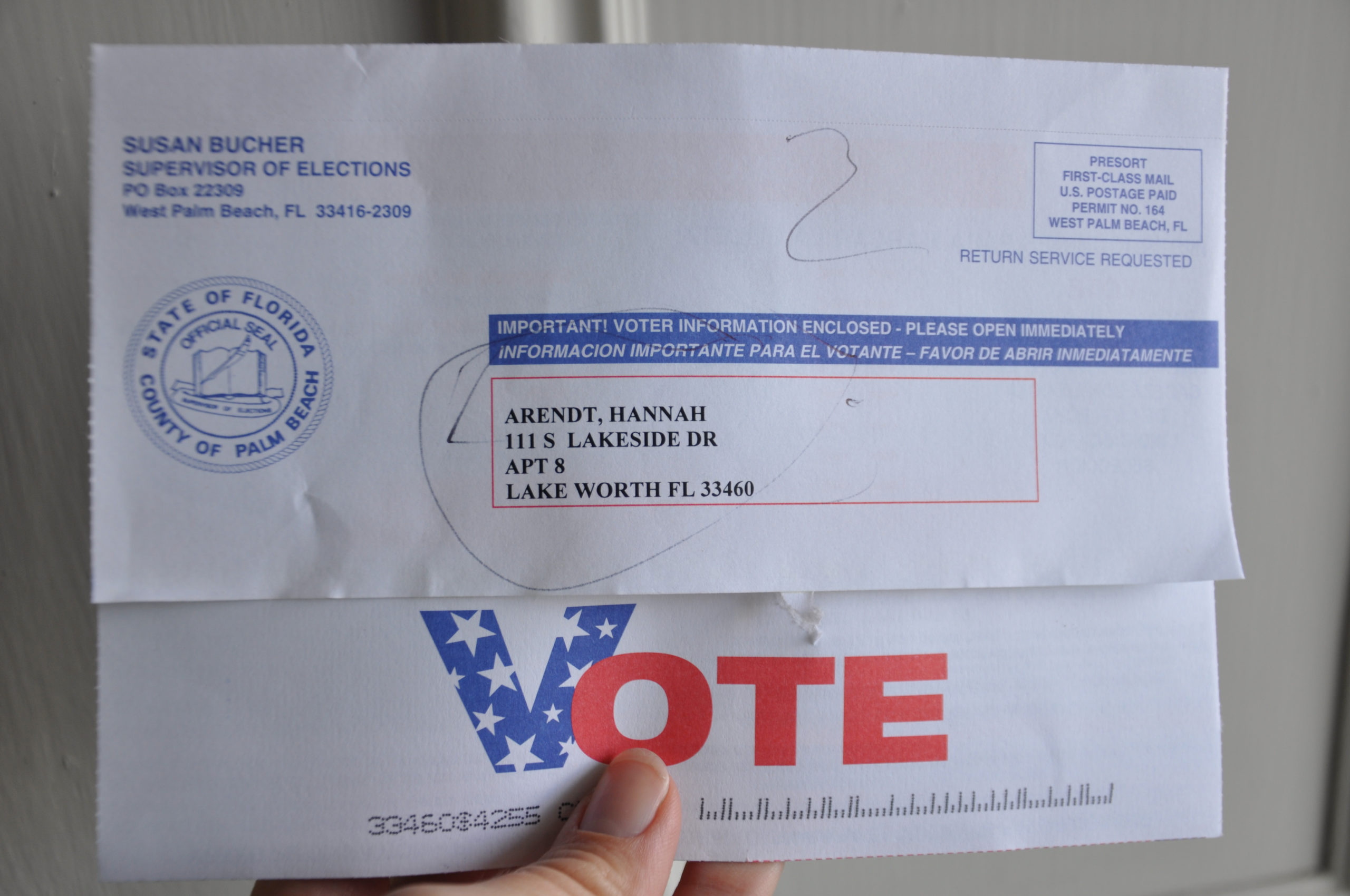

But I also received in my mailbox a new voter information card for Hannah Arendt.

On the outside of the card, my mailman had circled the name and address and written a question mark in pencil. But he still put it in my mailbox.

A few days later, I checked the Palm Beach County Supervisor of Elections website and sure enough, there was Hannah Arendt, listed as an eligible voter — a person who existed in history, the celebrated author of “Eichmann in Jerusalem” — but not a person who was in existence in 2011 in Palm Beach County, Florida.

Not long after, with an election approaching, I called the Palm Beach County Supervisor of Elections, said I was Hannah Arendt, and asked for an absentee ballot. The employee on the phone asked for a date of birth, and when I gave her information on my initial application — July 20, 1991 — she said she’d send one out.

The absentee ballot for Hannah Arendt appeared in my mailbox a week or two later.

I called a former Florida secretary of state in 2012 and asked him how was it possible that I was able to do this.

Well, he said, the fact is that they check names of people applying to register to vote against several different databases, but they have no way to check to see whether someone exists.

That’s just one way people can cheat with absentee ballots. There are many more.

Last year, a political operative working for North Carolina Republican congressional candidate Mark Harris was charged with fraud for directing a group of people to fill out as many as one thousand absentee ballot requests on behalf of voters — most of whom were unaware the ballots were being requested.

These people then collected the ballots and filled them out themselves. Harris defeated Democrat Dan McCready by just 905 votes and, though it was never shown that the number of tainted ballots was enough to account for Harris’s win, the election results were thrown out and a new election was held. (Republican Dan Bishop beat McCready in a special election by 2,400 votes.)

Also in 2019, a Democratic city clerk in Southfield, Michigan, was arrested and charged with six felonies for falsifying absentee ballot records to say that 193 of the ballots in one election were missing signatures or a return date, when in fact they had both. The correct records were found in the trash can in her office.

But J. Christian Adams of the Public Interest Legal Foundation (PILF) says if states aren’t careful, they’ll be issuing “an open invitation to fraud.”

“There are two big problems with vote by mail,” Adams told InsideSources. “Number one are the sort of things we discovered in the Justice Department when I was there — of people voting the ballot for other people through undue influence. That’s the first one. The second one — the voter rolls are a mess.”

Adams’ organization has sued several states and counties for refusing to maintain accurate voter rolls, allowing the names of thousands of dead voters, felons and non-citizens to remain in the system. Messy voter rolls make election fraud much easier, Adams says.

PILF is currently suing Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, for allowing the same person to register to vote seven times.

“It’s the exact same name, the exact same date of birth,” Adams said, as well as the same address. But the city and state won’t remove the extra registrations.

“In a vote by mail scheme, they’ll mail seven ballots,” he said.

States, I’ve since discovered, have no access to any master list of American citizens. So they can check to see if “Hannah Arendt” is a felon, or if she passed away as they can access death records.

But they have no way of checking to see whether an American citizen with that birth date exists. It’s an enormous hole in the ballot security system.

Eight years have passed, and I assumed that someone had taken ‘Hannah Arendt’ off the rolls by now.

But sure enough, when I checked the county website a few days ago, she was still there — with a message that read: “We have been unable to verify that this is your correct address. Please confirm or update your address with our office or use this website’s “Change of Address” feature before voting in the next election.”

I won’t be casting that fraudulent ballot. But I have to wonder: will my vote in the next election be canceled out by somebody who did?