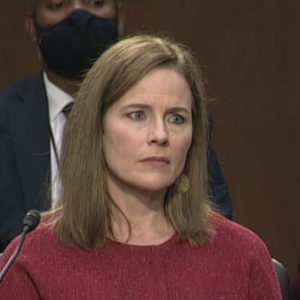

Amy Coney Barrett is now sailing toward confirmation, but not because we learned anything about her during last week’s hearings.

She showed herself to be gracious and poised, on top of a towering intellect, which is why the more Americans see of her, the more they like. But nothing came out about her judicial philosophy or views on cases that wasn’t already apparent from her academic and judicial writings.

Judge Barrett was charming and disarming — she did what she needed to do to get confirmed — but that showed this part of the process to be more Kabuki theater than oral exam.

Public confirmation hearings have only been around for a century, starting with Louis Brandeis’s nomination in 1916, which was contentious because he was Jewish and a progressive crusader. But Brandeis didn’t testify at his own hearing — that was seen as unseemly — and questioning of Harlan F. Stone in 1925 was limited to one corruption investigation he was pursuing as attorney general.

The first time a nominee took unrestricted questions in an open hearing was Felix Frankfurter in 1938. It simply wasn’t regular practice until the 1950s. At that point, the hearings became an opportunity for southern Democrats to rail against Brown v. Board of Education. Few senators other than the segregationists even asked the nominees questions.

Otherwise, hearings became perfunctory discussions of biography, as with Byron White in 1962, who was questioned for about 15 minutes, mostly about his football career. John Paul Stevens, the first nominee after Roe v. Wade, wasn’t even asked about that case. The focus in that post-Watergate time was on ethics.

Things changed in the 1980s, not coincidentally when the hearings began to be televised. Now all senators ask questions, especially about key controversies and fundamental issues, but nominees refuse to answer, creating what then-professor Elena Kagan called a “vapid and hollow charade.”

But even with this conventional narrative, there has been a subtle shift; from Robert Bork in 1987 through Stephen Breyer in 1994, nominees went into some detail about doctrine.

“This is not to say that nominees during those years made commitments about how they would rule on contested legal issues,” Chicago-Kent law professor Carolyn Shapiro explained on the eve of the Kavanaugh hearings. “But they did discuss their judicial philosophies, their past writings and their beliefs about the role of judges.”

Clarence Thomas discussed natural law and the role that the Declaration of Independence plays in constitutional interpretation. Ruth Bader Ginsburg talked about gender equality and the relationship between liberty and privacy.

Beginning with John Roberts in 2005, however, the nominees still covered the holdings of cases and what lawyers call “black letter law”— what you need to know to get a good grade in law school — but there’s been little revelation of personal opinions.

The nominees speak in platitudes: Roberts and his judicial umpire, Sonia Sotomayor saying that fidelity to the law was her only guidepost, Kagan accepting that “we’re all originalists now.”

Some of President Trump’s lower-court nominees have even been hesitant to state whether iconic cases like Brown were correctly decided, lest their inability to similarly approve of another longstanding precedent (notably Roe) cast doubt on its validity.

Barrett accepted Brown as a “super precedent” — because nobody seriously questions its validity — but wouldn’t pronounce on any other case. “I’m answering a lot of questions about Roe, which I think indicates that Roe doesn’t fall in that category [of cases that everyone has accepted].”

These days, senators try to get nominees to admit that certain cases are “settled law,” whether Roe when a Democrat questions a Republican nominee or the Second Amendment case District of Columbia v. Heller in the opposite circumstance.

Of course, when you’re dealing with the Supreme Court, law is settled until it isn’t, so nominees say that every ruling is “due all the respect of a precedent of the Supreme Court,” or some such. Which may or may not be a lot of respect, depending on the future justice’s view of stare decisis — the idea that some erroneous precedent should stand to preserve stability in the law and protect reliance interests.

And that’s before we even get to the “gotcha” questions, or last-minute accusations of sexual impropriety. So all this does is add to the toxic cloud enveloping Washington.

Amy Coney Barrett emerged unscathed from her theatrical audition — though perhaps we’re about to hear some revelation of how she cheated on a math quiz in junior high — but the experience does raise the question of whether we should continue this “hollow charade.”

Ilya Shapiro is the author of Supreme Disorder: Judicial Nominations and the Politics of America’s Highest Court.